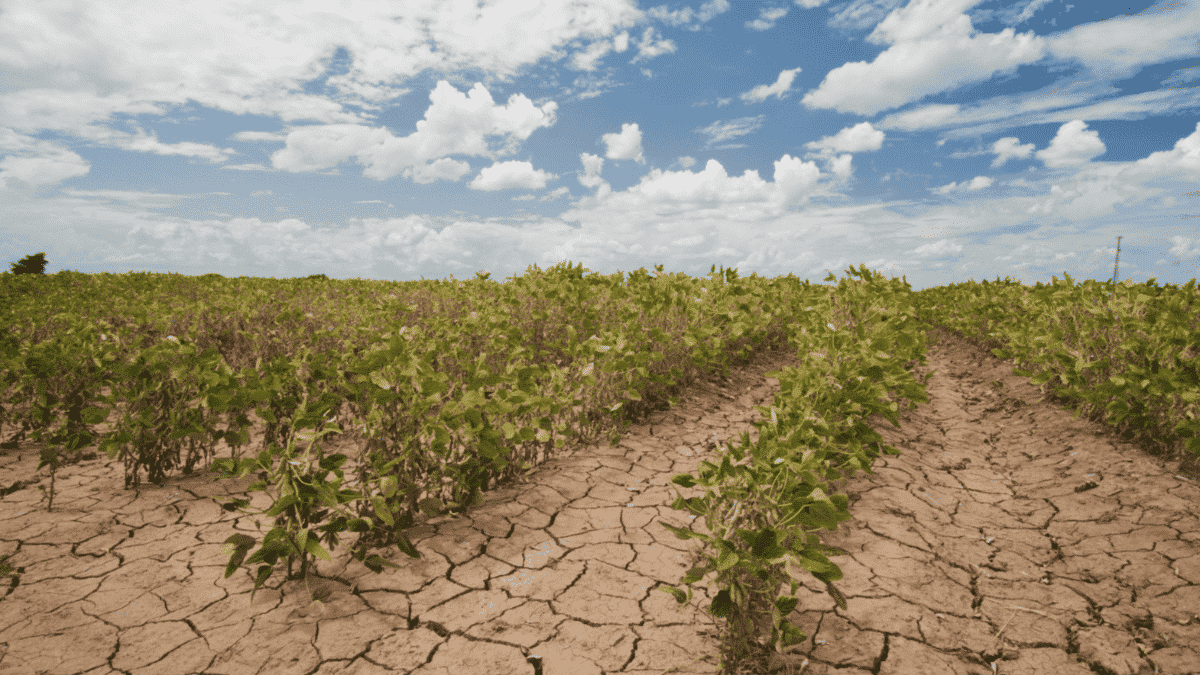

Soybean crops affected by a drought near Navasota, Texas on August 21, 2013. Bob Nichols / USDA / Smith Collection / Gado / Getty Images

By Keith Schneider

In many ways, the story of Texas over the last century is the state’s devout allegiance to the principle that mankind has dominion over nature.

The COVID-19 pandemic shut down that idea in 2020. By 11 October, nearly 800,000 people had been infected in Texas and over 16,000 died.

The sharp and irrepressible rise in virus cases and mortality adds to the intensifying view among Texans that far from living in a place distant from the vagaries of nature, Texas has become a national and global epicenter of natural calamity.

More people and businesses in Texas are in the way, as booming population and economic growth this century have written a much different story of vulnerability – to nature’s bullying and to government’s uncertain capacity to adjust. The state’s principal water research agency projects that demand for fresh water will increase dramatically by mid-century as supplies steadily drop, precipitating what looks like an inevitable supply crisis. In short, the second- largest American state and one of the world’s largest economies looks a lot like China, India, Australia, South Africa and every other place in the world contending with the confrontation between diminishing water supply and increasing demand.

“Texas does not understand shortages,” said Dr. Larry McKinney, one of the state’s top water researchers and the former director of the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies, a unit of Texas A&M University in Corpus Christi. “It’s the Texas mentality. Texas is so big we’ve had a hard time coming to grips that resources are finite. We really never had to deal with that. Frankly, we’re reaching that point.”

Rising Demand Confronts Lower Supplies

There are a couple of ways to examine the coming hardship. The first is in numbers. The Texas Water Development Board found that by 2070 the state’s population will grow to 51 million people, 22 million more than today. The state’s annual demand for water, the State Water Board projects, will climb to 21.6 million acre-feet (27 trillion liters), up from 18.4 million.

At the same time, a severe drought will bring increasing constraint. State authorities project that in a drought comparable to the most severe on record, water supplies will fall over the next 50 years from 15.2 million acre-feet to 13.6 million acre-feet (17 trillion liters). During the driest periods, more people will have considerably less water.

Here’s how that confrontation is playing out in the Hill Country, a region of rapid population growth and uncertain water supply west of Austin, Texas’ capital city.

Two generations ago, about 40,000 people made their homes in Hays County, an epic, rural, rolling masterpiece of space and sky close to Austin and San Antonio. Authorities in Hays counted 14,000 homes that were supplied with water from the Trinity Aquifer, a giant freshwater reserve that lay below. In both wet years and dry, water was readily available.

Four decades later, Hays County has grown to 222,000 residents and 75,000 housing units. The Trinity Aquifer is tapped out. Since 2003, a pipeline from Lake Travis, a reservoir near Austin, has provided developers with sufficient water to continue building big subdivisions.

But a study by the Hill Country Alliance and the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment at Texas State University in San Marcos found that the piped water encouraged more drilling fo water wells into the aquifer. In one area, they found that pumping jumped from just over 3 million gallons annually to 90 million gallons (409 million liters).

The idea of the sanctity of economic expansion produces all manner of conflict and turmoil about water throughout Texas. The annual .89 trillion Texas economy, the second-largest state economy and ninth-largest in the world, is entirely dependent on access to adequate supplies of water.

The 2011 drought caused more than billion in agricultural losses, and indirect costs of .9 billion. From 1980 to 2018, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Texas also led all states, by far, in losses from severe storms and flooding. In 2017 alone, Hurricane Harvey, a Category 4 storm that stalled near Houston, caused 5 billion in damages.

“Water is the economy in Texas,” said McKinney. “It drives everything, particularly as you get less of it.”

Sound familiar? It should. Struggles over water occurring across Texas are essentially the same as those unfolding in places where growth is highest and water resources are under the most stress. In the United States that means California, the Southwest and the Rocky Mountain West.

The same two trends are unfolding around the planet, most notably in China and India. In 2011, China discovered that its program of energy development, grain production, and construction of new cities was using so much water that by 2020 it would be 20 to 25 trillion liters in deficit, a shortage so dire it could wreck China’s booming economy.

A command-and-control society, China aggressively set out to shrink the deficit by quickly acting on three big initiatives. It moved much of its grain production from the dry Yellow River Basin to the wet northeast provinces. It closed water-thirsty coal mines, coal-washing stations, and water-cooled coal-fired power stations. And it built the largest water-conserving solar and wind electrical generating industry on Earth.

India is having less success. Groundwater levels are steadily declining in the northwest states that produce much of country’s rice, wheat, and sugarcane. But the state and national governments encourage the trend. In a nation that has known pervasive hunger, food production is a paramount cultural objective. Keeping the 700 million Indians who are involved in agriculture happy is another prime objective. That’s why farmers pay nothing for water. They can use what they like. And they pay nothing for electricity to run ever-more powerful pumps needed to pull water to the surface that lies ever-deeper below ground.

Texas is Texas. Texas is big, rich, growing, impulsive and impressive. The significant question Texas hasn’t answered is where it will find enough water by 2070 – 10 trillion liters, according to the Texas Water Development Board, or about half the Chinese water deficit – to keep over 50 million people safe, satisfied and thriving during deepening droughts.

There are two ways to look at the challenge. The most optimistic view is so Texas. The Water Board, with its process of reviewing and revising the State Water Plan every five years, lays out steps that are meant to give Texas guidance and time to figure it out. The more realistic and accurate assessment is that as Texas pursues its steep growth vector, the hardships of serious droughts will grow worse.

Reposted with permission from World Economic Forum.

- Drought-Stricken Texas Fracks Its Way to Water Shortages - EcoWatch

- A Twenty-First Century Water War Erupts in Texas - EcoWatch

- Brain-Eating Amoeba Found in Texas City's Water Spurs Disaster ...

- Texas Blackout: Death Toll Mounts, Food and Water Are Impacted

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe