How a Scientific Spat Over How to Name Species Turned Into a Big Plus for Nature

Pexels

By Stephen Garnett, Les Christidis, Les Christidis and Scott Thomson

Taxonomy, or the naming of species, is the foundation of modern biology. It might sound like a fairly straightforward exercise, but in fact it’s complicated and often controversial.

Why? Because there’s no one agreed list of all the world’s species. Competing lists exist for organisms such as mammals and birds, while other less well-known groups have none. And there are more than 30 definitions of what constitutes a species. This can make life difficult for biodiversity researchers and those working in areas such as conservation, biosecurity and regulation of the wildlife trade.

Scientists worked out a few differences over how to name species. Laurent Gillieron / EPA

How It All Began

In May 2017 two of the authors, Stephen Garnett and Les Christidis, published an article in Nature. They argued taxonomy needed rules around what should be called a species, because currently there are none. They wrote:

for a discipline aiming to impose order on the natural world, taxonomy (the classification of complex organisms) is remarkably anarchic […] There is reasonable agreement among taxonomists that a species should represent a distinct evolutionary lineage. But there is none about how a lineage should be defined.

‘Species’ are often created or dismissed arbitrarily, according to the individual taxonomist’s adherence to one of at least 30 definitions. Crucially, there is no global oversight of taxonomic decisions — researchers can ‘split or lump’ species with no consideration of the consequences.

Garnett and Christidis proposed that any changes to the taxonomy of complex organisms be overseen by the highest body in the global governance of biology, the International Union of Biological Sciences (IUBS), which would “restrict […] freedom of taxonomic action.”

An Animated Response

Garnett and Christidis’ article raised hackles in some corners of the taxonomy world – including coauthors of this article.

These critics rejected the description of taxonomy as “anarchic.” In fact, they argued there are detailed rules around the naming of species administered by groups such as the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature and the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants. For 125 years, the codes have been almost universally adopted by scientists.

So in March 2018, 183 researchers – led by Scott Thomson and Richard Pyle – wrote an animated response to the Nature article, published in PLoS Biology.

They wrote that Garnett and Christidis’ IUBS proposal was “flawed in terms of scientific integrity […] but is also untenable in practice”. They argued:

Through taxonomic research, our understanding of biodiversity and classifications of living organisms will continue to progress. Any system that restricts such progress runs counter to basic scientific principles, which rely on peer review and subsequent acceptance or rejection by the community, rather than third-party regulation.

In a separate paper, another group of taxonomists accused Garnett and Christidis of trying to suppress freedom of scientific thought, likening them to Stalin’s science advisor Trofim Lysenko.

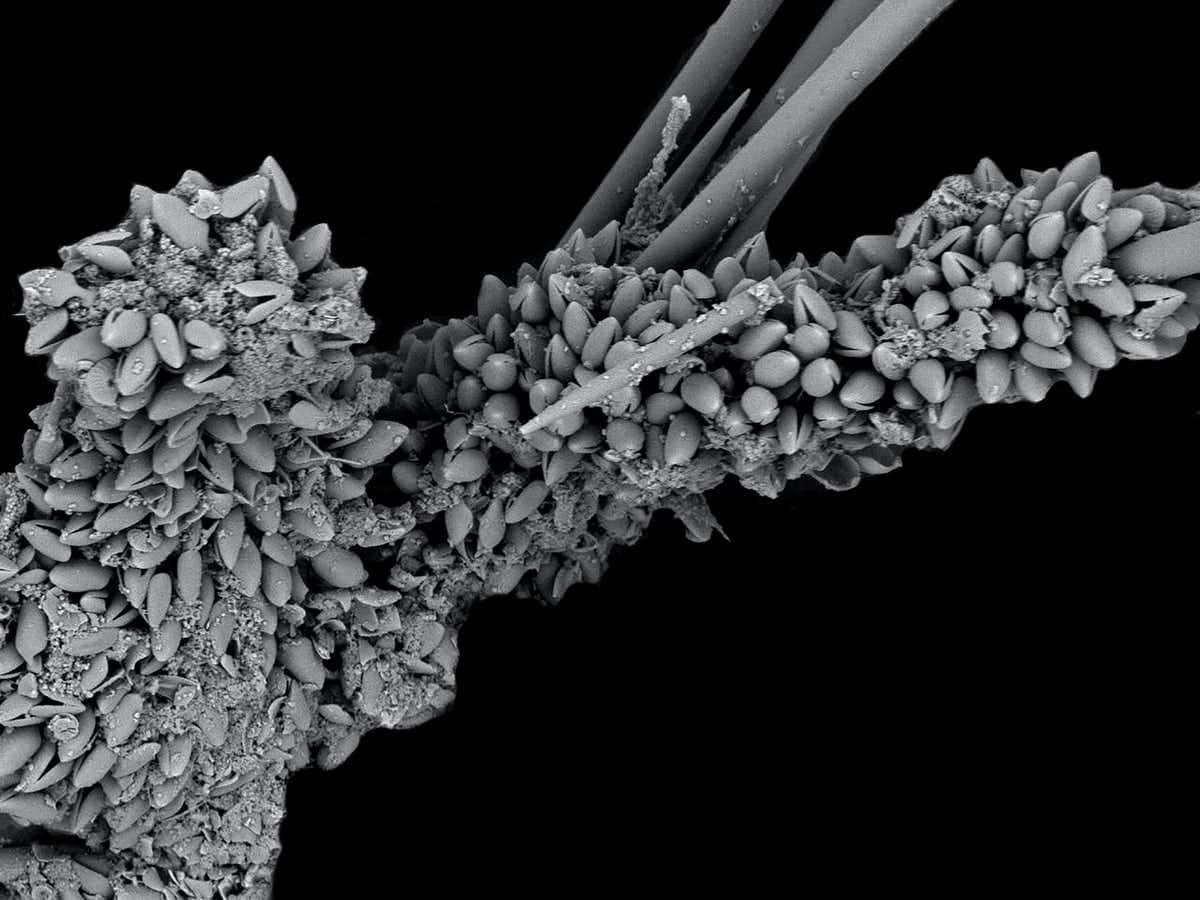

Taxonomy can influence how conservation funding is allocated. Queensland Museum

Finding Common Ground

This might have been the end of it. But the editor at PLoS Biology, Roli Roberts, wanted to turn consternation into constructive debate, and invited a response from Garnett and Christidis. In the to and fro of articles, we all found common ground.

We recognised the powerful need for a global list of species – representing a consensus view of the world’s taxonomists at a particular time.

Such lists do exist. The Catalogue of Life, for example, has done a remarkable job in assembling lists of almost all the world’s species. But there are no rules on how to choose between competing lists of validly named species. What was needed, we agreed, was principles governing what can be included on lists.

As it stands now, anyone can name a species, or decide which to recognise as valid and which not. This creates chaos. It means international agreements on biodiversity conservation, such as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) and the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS), take different taxonomic approaches to species they aim to protect.

We decided to work together. With funding from the IUBS, we held a workshop in February this year at Charles Darwin University to determine principles for devising a single, agreed global list of species.

Participants came from around the world. They included taxonomists, science governance experts, science philosophers, administrators of the nomenclatural (naming) codes, and taxonomic users such as the creators of national species lists.

The result is a draft set of ten principles that to us, represent the ideals of global science governance. They include that:

- the species list be based on science and free from “non-taxonomic” interference

- all decisions about composition of the list be transparent

- governance of the list aim for community support and use

- the listing process encompasses global diversity while accommodating local knowledge.

The principles will now be discussed at international workshops of taxonomists and the users of taxonomy. We’ve also formed a working group to discuss how a global list might come together and the type of institution needed to look after it.

We hope by 2030, a scientific debate that began with claims of anarchy might lead to a clear governance system – and finally, the world’s first endorsed global list of species.

The following people provided editorial comment for this article: Aaron M Lien, Frank Zachos, John Buckeridge, Kevin Thiele, Svetlana Nikolaeva, Zhi-Qiang Zhang, Donald Hobern, Olaf Banki, Peter Paul van Dijk, Saroj Kanta Barik and Stijn Conix.

Stephen Garnett is a Professor of Conservation and Sustainable Livelihoods at Charles Darwin University. Les Christidis is a Professor at Southern Cross University. Richard L. Pyle is a Associate lecturer at the University of Hawaii. Scott Thomson is a Research associate at the Universidade de São Paulo.

Disclosure statement:

Stephen Garnett receives funding from International Union for Biological Sciences, the Australian Research Council and the National Environment Science Program

Les Christidis receives funding from the International Union for Biological Sciences.

Richard L. Pyle receives funding from U.S National Science Foundation, NOAA (U.S.), U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Scott Thomson is affiliated with the Chelonian Research Institute and the IUCN Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group. The first is a not for profit organisation,

Reposted with permission from The Conversation.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe