By Justin Mikulka

The Motley Fool has been advising investors on “How to Profit From the Re-Emergence of Canada’s Crude-by-Rail Strategy.” But what makes transporting Canadian crude oil by rail attractive to investors?

According to the Motley Fool, the reason is “… right now, there is so much excess oil being pumped out of Canada’s oil sands that the pipelines simply don’t have the capacity to handle it all.”

The International Energy Agency recently reached the same conclusion in its Oil 2018 market report.

“Crude by rail exports are likely to enjoy a renaissance, growing from their current 150,000 bpd [barrels per day] to an implied 250,000 bpd on average in 2018 and to 390,000 bpd in 2019. At their peak in 2019, rail exports of crude oil could be as high as 590,000 bpd—though this calculation assumes producers do not resort to crude storage in peak months,” the International Energy Agency said, as reported by the Financial Post.

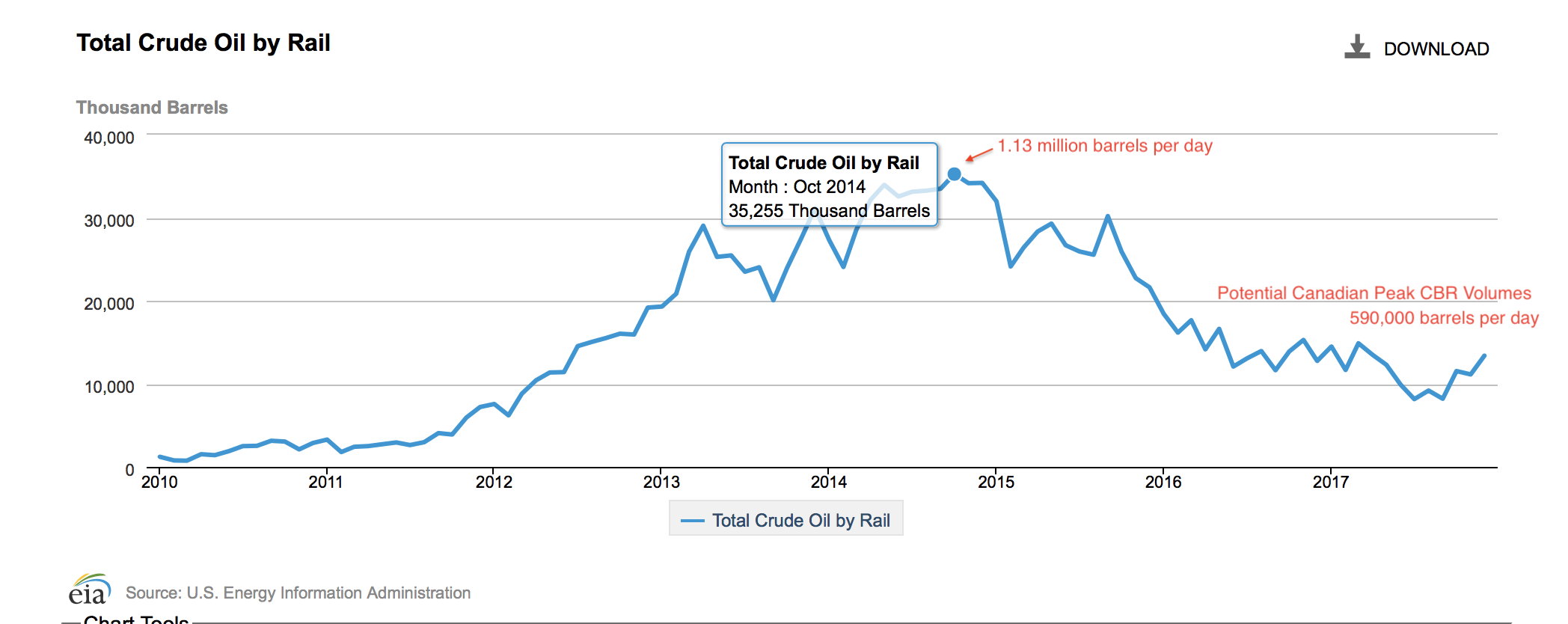

To put that in perspective, however, the industry was moving 1.3 million barrels per day at the peak of the U.S. oil-by-rail boom in 2014.

Graph of American crude-by-rail volumesU.S Energy Information Administration

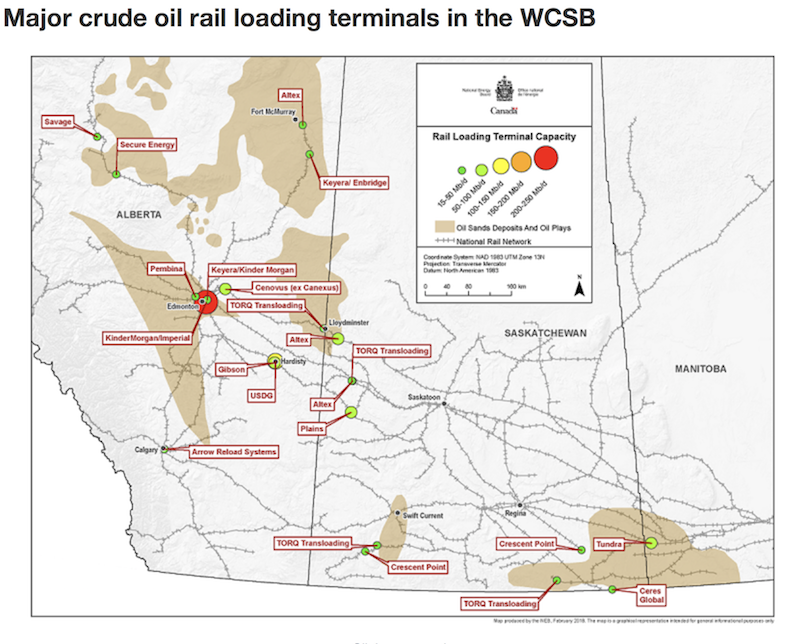

And Canada has plenty of capacity to load oil on more trains, which means if a producer is willing to pay the premium to move oil by rail, it can find a customer to do it. The infrastructure is in place to load approximately 1.2 million barrels per day.

Canadian crude-by-rail loading facilities National Energy Board

With the cancellation of the Energy East pipeline project, which would have moved western Canada’s tar sands east to Québec and New Brunswick, the industry now is pursuing two remaining major pipeline projects: Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain and the Keystone XL. The Financial Post reported that the International Energy Agency predicts the earliest start date for either of those projects as 2021. Both pipelines are facing fierce opposition.

Additionally, the surge in U.S. crude oil exports has been affecting the value of Canadian oil, and some are predicting the flood of U.S. crude abroad could deliver a serious blow to the tar sands industry in the long-term.

Over the next several years, however, the Canadian tar sands industry appears poised to rely heavily on rail to export its product while awaiting construction of new pipelines, much like the situation that led to the Bakken oil-by-rail boom in the U.S.

Risks of Canadian Oil by Rail Are Unknown

When hydraulic fracturing (fracking) turned North Dakota into a major oil producer, the state had little pipeline capacity. But it did have railroad tracks, many built over a century earlier, crisscrossing its plains.

As a result, the oil industry started filling up trains with highly volatile oil—under virtually no regulatory oversight—and in the process invented what rail workers would come to call “bomb trains.” After the trains hauling Bakken oil in unsafe tank cars began exploding, it became apparent that the Bakken oil was the culprit.

As the Canadian oil industry begins to ramp up its rail exports, has it learned anything from the Bakken “bomb train” experiment (which in 2013 claimed 47 lives in Lac-Mégantic, Québec)?

Unfortunately, the industry appears to have learned very little. While it no longer uses the most dangerous DOT-111 tank cars to ship oil, most of the major oil train derailments and fires actually have involved the newer CPC-1232 tank cars, which make up the majority of the oil tank car fleet.

In addition, the rail industry has refused to use modern braking systems to improve safety and was able to get U.S. regulators to repeal a rule requiring modern brakes on oil trains. The industry is also fighting proposed regulations requiring two-person crews for oil trains.

Furthermore, it remains unclear what exactly will be inside those tank cars.

Will the industry choose to move some form of diluted bitumen or synthetic crude or raw bitumen? That information isn’t available but makes a big difference when evaluating the risks posed by these trains.

Raw bitumen requires special tank cars that can be heated (to allow the thick, viscous bitumen to be pumped in and out) as well as the infrastructure to heat the cars. To date, there is little evidence the industry is moving much raw bitumen by rail. That leaves the option of pumping the cars full of diluted bitumen or synthetic crude oil (a processed intermediate product derived primarily from tar sands which is apparently chemically identical to conventional crude oil).

There have been two significant derailments of Canadian crude by rail—whether the oil was synthetic crude derived from tar sands is unconfirmed, but likely. Coincidentally, the derailments occurred just three weeks and several miles apart near the town of Gogama, Ontario. Both trains exploded and burned for days. The public was not allowed near the crash sites. One of the trains had several tank cars end up in the Makami River, which was contaminated by a large oil spill.

The Transportation Board of Canada reported that the material in the tank cars was “Horizon Sweet Light Oil.” The agency described it as “synthetic crude oil distillate; sweet light oil” and was classified as Packing Group 1—which is the most dangerous classification. To put that in perspective, Packing Group 1 is a higher risk classification than the oil involved in the deadly Lac-Mégantic disaster.

Oil samples taken from the 2015 Gogama train crashTransportation Safety Board of Canada

Additionally, the Gogama crashes were caused by track failures. The American rail industry has successfully fought for years against any regulations on rail wear, and current rail regulations are stalled in the Trump administration.

More Oil Trains, Still No Spill Response Plans

A 1996 U.S. legal loophole exempts oil and rail companies from needing spill response plans for oil trains. This gap in oil spill regulations came to light during the U.S. boom in oil train traffic more than four years ago and has not been resolved yet.

However, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) has proposed a rule to change that. According to a Department of Transportation report, the regulation is in the “Final Rule” stage, but a PHMSA spokesperson was unable to provide further detail on the timing or status of the rule actually taking effect. There is no guarantee the proposed rule, which would require oil spill response plans for trains carrying at least 20 continuous cars of liquid petroleum oil or 35 cars throughout the train, won’t simply languish under the Trump administration.

Another troubling aspect of this latest surge in oil-by-rail traffic is the fact that the oil industry, scientists, and U.S. and Canadian governments are still getting a grasp on how different types of tar sands oil behave when spilled in fresh and saltwater environments. One large tar sands oil spill in Michigan’s Kalamazoo River in 2010 and subsequent studies hint that there’s more to the picture than the industry’s spin that tar sands oil spills are no different than other crude oils.

Local Governments Taking Action

With the Trump administration actively rolling back safety regulations for oil trains, some U.S. states and communities are taking the initiative to protect themselves from the risks of tar sands oil and oil trains.

Washington state has been a battleground in the fight against new oil-by-rail infrastructure. The recent decision to reject the proposed Vancouver Energy oil-by-rail project at the Port of Vancouver was a major victory for that movement and the latest in a string of such efforts on the West Coast.

Washington is also taking things a step further and is now requiring rail companies to have oil spill response plans. The state recently approved such plans for oil-by-rail leader BNSF.

“This plan is a significant step forward for the protection of Washington’s communities and environment,” said Dale Jensen, the spills prevention program manager for the state of Washington. “Oil by rail has expanded significantly in recent years, and it’s imperative railroad companies are prepared to work with the state to respond to a spill in a rapid, aggressive, and well-coordinated manner.”

In New Jersey, earlier efforts to improve oil-by-rail safety were vetoed by then-Governor Chris Christie, but they have been restarted now that Christie is no longer governor. The proposed plans “would require railroads to develop oil spill response plans in case of a derailment.”

More recently, the city of Baltimore voted to ban the construction of new facilities that could be used to export crude oil from its port, an effort specifically targeting proposed oil-by-rail projects. This is a similar approach to South Portland, Maine‘s ban on loading crude oil onto ships and to Albany, New York’s efforts to stop tar sands by rail. These bans take on new significance now that the first ocean-going tanker was recently filled with Canadian tar sands oil, which arrived by rail in Portland, Oregon and is destined for China.

The first wave of oil trains in North America resulted in several major oil spills and the deaths of 47 people in Lac-Mégantic, Québec. However, there were several other very close calls with oil train crashes in recent years, resulting in multiple declarations of how lucky communities were that there weren’t more deaths due to these oil train derailments.

With no meaningful changes to how they are regulated, this second wave of oil trains will need that lucky streak to continue holding.

New Technology Could Turn Tar Sands Oil Into 'Pucks' for Less Hazardous Transport https://t.co/HzZa2Wuvzx @ScienceNewsOrg @TheScienceGuy

— EcoWatch (@EcoWatch) February 19, 2018

Reposted with permission from our media associate DeSmogBlog.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe