Study Finds Up to One Billion Birds Killed in Building Collisions Each Year

In the most comprehensive study of its kind, involving the review and analysis of almost two dozen studies and more than 92,000 records, federal scientists have found that between 365 and 988 million birds are likely killed in the U.S. each year as a result of collisions with buildings.

The study, Bird–Building Collisions in the U.S.: Estimates of Annual Mortality and Species Vulnerability was published in a peer-reviewed journal, The Condor: Ornithological Applications in Jan. 2014. It was authored by Scott R. Loss, Sara S. Loss, and Peter P. Marra of the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and Tom Will of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“Our analysis indicates that building collisions are among the top anthropogenic threats to birds and, furthermore, that the several bird species that are disproportionately vulnerable to building collisions may be experiencing significant population impacts from this anthropogenic threat,” the authors say.

The study provides quantitative evidence to support the conclusion that building collisions are second only to feral and free-ranging pet cats (estimated to kill as many as 3 billion birds each year) as the largest source of direct human-caused mortality for U.S. birds.

The Data on Buildings and Birds

In examining by far the largest building collision dataset collected to date—92,869 individual records—the scientists: (1) systematically quantified total bird collision mortality; (2) generated estimates of mortality for different classes of buildings (including residences from one to three stories tall; low-rise nonresidential buildings and residential buildings from four to 11 stories tall; and high-rise buildings more than 12 stories tall); (3) conducted sensitivity analyses to identify which model parameters contributed the greatest uncertainty to mortality estimates; and (4) quantified species-specific vulnerability to collisions across all buildings and for each building type.

Based on their analyses of 23 studies, they found that roughly 56 percent of mortality occurred at low-rises, 44 percent at residences and one percent at high-rises. The annual bird mortality at residences was estimated to be between 159 and 378 million birds (median 253 million); between 62 and 664 million birds (median 246 million) at low-rise buildings; and between 104,000 and 1.6 million birds (median 508,000) at high-rise buildings.

Even though the number of collisions at each high-rise building is high, the total number of these buildings is smaller; the larger number of low-rises and especially homes produces high total mortality.

According to American Bird Conservancy’s (ABC) Dr. Christine Sheppard, who heads the only national collisions campaign program in the U.S.: “This study presents a significantly more robust estimate and a much-needed refinement of the data on building collision mortality. The improved understanding and credibility it provides on the issue will help us better advance collision reduction efforts such as those we’ve already seen in places such as San Francisco, Oakland, Minnesota and Toronto.”

Sheppard authored the widely used publication, Bird-Friendly Building Design which provides comprehensive solutions to reduce bird mortality from building collisions. The 58-page publication contains more than 110 photographs and 10 illustrations and focuses on both the causes of collisions and the solutions, with a comprehensive appendix on the biological science behind the issue.

Bird Species Most Impacted by Building Collisions

According to the study, the species most commonly reported as building kills (collectively representing 35 percent of all records) were White-throated Sparrow, Dark-eyed Junco, Ovenbird and Song Sparrow. However, the study found that some species are disproportionately vulnerable to building collisions. Several of these are birds of national conservation concern and fall victim primarily to certain building types. Those species include:

- Golden-winged Warbler and Canada Warbler (low-rises, high-rises and overall)

- Painted Bunting (low-rises and overall)

- Kentucky Warbler (low-rises and high-rises)

- Worm-eating Warbler (high-rises)

- Wood Thrush (residences)

For species that are vulnerable to collisions at more than one building class or overall—including Golden-winged Warbler, Painted Bunting, Kentucky Warbler and Canada Warbler—building collision mortality appears substantial and may worsen population declines. For species identified as highly vulnerable to collisions for one building class but not across building types (Wood Thrush at residences, Worm-eating Warbler at high-rises), building collisions may still represent a threat to populations.

Several species exhibit high vulnerability to collisions (relative to population size) regardless of building type, including Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Brown Creeper, Ovenbird, Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, Gray Catbird and Black-and-white Warbler.

Tips from ABC on Reducing Bird Collisions at Home

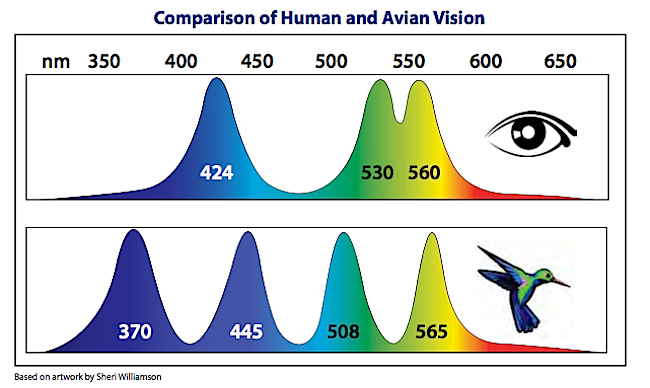

When it comes to preventing bird collisions, home-owners have a vital role to play. In general, the goal is to make windows—which birds can’t see as people do—visible. There are several easy ways to do this:

- General guidelines: Affixing a pattern of tapes or other materials to windows can help make the glass visible to birds. Most birds will avoid windows with vertical stripes spaced four inches apart, or horizontal stripes spaced two inches apart. More complicated or irregular patterns will also work as long as they follow those general guidelines. For best results, patterns must be on the outside surface of the windows.

- ABC has create a product especially for the purpose of preventing home window collisions. ABC BirdTape—created with the support of the Rusinow Family Foundation—is made to last outdoors, easy to use, and inexpensive.

- You can use basic craft supplies to make windows safer for birds. Apply tempera paint (available at most art and craft stores) freehand with brush or sponge, or use a stencil. Tempera is nontoxic and long lasting, even in rain, but comes right off with a damp rag or sponge.

- Find stencils at craft stores or download free stencils online. Make seasonal designs a family project. Use tape to create patterns. Any opaque tape can work, but translucent ABC BirdTape transmits light and is made to last outdoors.

- Most window films designed for external use are not patterned and will not deter birds. However, interior window films come in many colors and styles, and can be applied on the outside of windows to prevent collisions.

- If you don’t want to alter the glass itself, you can stretch lightweight netting, screen, or other material over the window. The netting must be several inches in front of the window, so birds don’t hit the glass after hitting the net. Several companies sell screens, solar shades, or other barriers that can be attached with suction cups or eye hooks.

- Prefabricated decals can work if spaced properly. The shape does not matter; birds see decals shaped like raptors as obstacles but not as predators. To be effective, decals must be spaced no more than four inches apart horizontally or two inches apart vertically—more closely than recommended by most manufacturers.

Visit EcoWatch’s BIODIVERSITY page for more related news on this topic.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe