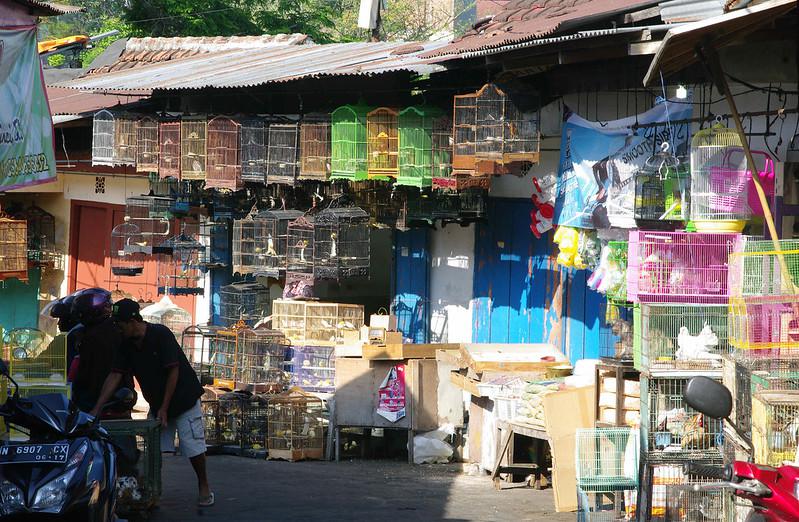

Yogyakarta Bird Market, Central Java, Indonesia. Jorge Franganillo / CC BY 2.0

By John R. Platt

The straw-headed bulbul doesn’t look like much.

It’s less than a foot in length, with subdued brown-and-gold plumage, a black beak and beady red eyes. If you saw one sitting on a branch in front of you, you might not give it a second glance.

But this Southeast Asian native stands out in one notable way: It sings like an angel.

“It’s arguably the most beautiful song of any bird,” says Chris Shepherd, executive director of Monitor Conservation Research Society and an expert on Asian songbirds. “It’s amazing,” he adds.

The bird’s beautiful voice serves a vital ecological purpose: Males use it to attract mates. The better the song, the greater the chance of finding a female and propagating the species.

But the song has also come with a terrible modern cost. Humans have come to value the bulbul’s calls so much that they’ve collected the birds from almost every inch of their habitat. Captured birds, quickly caged, have been shipped to markets throughout Southeast Asia. Due to this overwhelming commercial demand, the species has disappeared from most of its range and is now critically endangered. Only a few pocket populations continue to hang on.

And the straw-headed bulbul is far from alone in this decline. Practically every songbird species in Southeast Asia faces a similar predicament. Many birds face the very real risk of imminent extinction, leaving some forests in the region eerily silent.

Recent research finds that several songbirds have become perilously close to vanishing — if they haven’t been lost already.

One Indonesian bird, the Simeulue hill myna, has only just been described as genetically and morphologically unique from other lookalike species. It probably went extinct in the wild in the past two or three years, according to a paper published last spring in the journal Ibis. As the researchers wrote, “On multiple recent excursions to Simeulue, most recently in July 2018, we were unable to find the bird and learned from locals that there had been a great drive to catch the last survivors on the island in response to a wealthy person’s bounty on these birds.”

The paper calls this an “extinction-in-process” and warns that any remaining birds left in captivity may die without producing offspring. Even if they do manage to breed, the researchers fear they could be hybridized with other similar-in-appearance mynas, obscuring their genetic lineage.

That same phrase, extinction-in-process, has also been used to describe the Barusan shama, which according to a 2019 study published in the journal Forktail has become one of the most threatened of Asian songbirds due to rampant collection. It’s now gone from all but one island.

Like the Simeulue hill myna, the Barushan shama’s plight went virtually unnoticed for years because many taxonomists have classified it as a subspecies rather than a full species. Newer research finds that it’s a species with four subspecies, few of which may now survive.

Not that the species/subspecies disputes matter too much at this point.

“Taxonomic debates about the rank of these forms should not stand in the way of trying to ensure the survival of what is clearly an evolutionarily distinct lineage,” says Frank Rheindt, a biologist with National University of Singapore and senior or lead author on both of the papers.

So what happens to these birds once they’re taken from the wild?

That’s where the story gets even bleaker.

Disposable Love

Songbirds are an important element of culture and tradition for many peoples in Southeast Asia. In Java, for example, it’s almost assumed that every household will have at least one pet songbird. The more birds, the more prestigious the home.

But wild songbirds in captivity…well, they don’t tend to last long.

“We’ve often called the caged songbird trade like cut flowers,” says Shepherd. “The birds look nice. They’re often inexpensive. You bring one home. It sits in a cage for a couple of days and it dies just like a cut flower. They’re not expected to live.”

And because many Asian cities feature massive markets full of birds that have been easily snatched from the wild — usually illegally — any bird that dies is relatively easy and inexpensive to replace.

Cages line the Malang bird and animal market on Java in 2016. Andrea Kirkby / CC BY-SA 2.0

Even bird traders don’t put much value on their stock, since a new supply of wild-caught birds always seems to be waiting in the wings.

“I’ve seen some cages where the surviving birds are all sitting on top of dead birds in the cages,” Shepherd says. “You can’t see the floor of the cage. It’s covered with a few layers of dead birds, and then there’s some sick and half-dead birds perched on top of them. And they cost the dealers next to nothing. So, you know, even if they sell a few, they think they must be covering their costs or you wouldn’t have a business model like that.”

Although all of this seems to favor low-cost disposability, some species are captive bred by the thousands, and prices can soar for the right birds.

As with so many other groups of heavily traded species, the rarest birds fetch higher prices from collectors — a “better get them before they’re gone” collector’s mentality that pushes prices higher, drives further poaching and drives birds even closer to extinction.

The Simeulue hill myna, for instance, might have sold for about 0-0, “certainly if a foreigner or non-Simeulue person asks,” says Rheindt. “This is easily 2-4 monthly incomes for rural people on the island.”

The Caged Bird Sings

Along with its rarity, a bird’s appearance is clearly a valuable trait to collectors. Some of the birds are strikingly beautiful, like birds of paradise and the Javan white-eye.

A kingfisher, looking a little worse for wear, in the Malang bird and animal market in 2016. Andrea Kirkby / CC BY-SA 2.0

But the quality that typically drives up a bird’s market price?

That, of course, would be the song.

A good song can earn a bird owner a big payday. Entire competitions have sprung up that offer cash prizes for the birds with the best songs — up to ,000, according to some reports. On Java these events are known as Kicau-mania (“kicau” is Indonesian for “chirping”).

The bird doesn’t get much for his work. Perhaps some food and a chance to sing again.

But it can take a lot of human effort to inspire them to sing for their suppers.

“People will keep the male birds in captivity for a long time,” says Shepherd. “Some birds don’t want to sing in captivity and take a long time before they adjust to the point where they’ll start to sing. Then they’ll train the bird. They’ll keep it near other males so it sings more frequently, because they naturally compete with their songs.”

This forced companionship changes the very nature of the song.

“Some birds pick up notes and sounds from other species,” Shepherd says. “Some of the species that are disappearing, they’re just training birds. They’re not even the ones used in competition. They just keep them beside other the species that compete so they have a more complex and unique song in the competition.”

After that, it’s a bit like a dog show.

“Everybody takes their bird in a cage and there are songbird judges. They walk around and listen to the song and there’s big cash prizes for the bird with the best.” (Most recently, these competitions have moved online due to COVID-19.)

Through all of this, the gift nature gave these animals to help propagate their species — song — ends up driving them toward extinction.

This makes the trade similar to trophy hunting, which values the biggest animals or those with the most beautiful features. “The strongest bird in the wild, the one with the greatest song, would be the one that would pass on his genes,” Shepherd says. “Those are the ones being removed from the wild. So, you know, only inferior birds are left behind.”

Unlike trophy hunting, however, where an elephant’s tusks can theoretically trade hands in perpetuity, a bird’s song is ephemeral — sung once, then lost to time.

Progress

Shepherd says the Asian songbird crisis went virtually ignored for many years. Relatively few scientists studied it, and funding for conservation remained scarce. That’s been a costly delay.

“One of the interesting and sad things is that lot of the species that I worked on in the early Nineties, the ones I tried to raise the alarm on, are now gone or almost gone,” he says. “And then the ones I was working on that were extremely common at the time are now the next wave that’s disappearing.”

Fortunately, that’s started to change. For one thing, scientific research about the trade and affected species continues to pick up. One of the most worrying studies came out last August and found that Java now has more songbirds in cages than in its forests. The study found that one species, the Javan pied starling (Gracupica jalla), now has fewer than 50 birds remaining in the wild, while 1.1 million live on the island in captivity.

Meanwhile governments, NGOs and other researchers have also stepping up their game. Conservation experts came together in 2015 to hold an event called the Asian Songbird Trade Crisis Summit. Two years later they formed the IUCN Asian Songbird Trade Specialist Group, which had its first official meeting in 2019. And over the past five years governments have started to take action, including seizing several large shipments of poached birds, although the trade remains mostly illegal and unsustainable.

Local groups have helped, too, which brings us back to the Simeulue hill myna and Barusan shama. A Simeulue-based organization called Ecosystemimpact set out to help the two birds at the beginning of 2020. Although their efforts were hampered by the COVID pandemic, they’re still trying to acquire any captive birds they can find to keep them out of the trade. If they do rescue any Simeulue hill mynas — such as four juvenile birds that reportedly recently turned up for sale on Facebook — they’ll need a permit from the government to breed them.

Even then, saving them from extinction won’t be easy.

“Hill myna are notoriously hard to breed, requiring large, tall aviaries with good vantage points over forested areas,” says program manager Tom Amey. “It’s not out of the question that hill myna will breed within our aviaries, but given their specific requirements, we feel it is unlikely.” They’re working on raising funding for new aviaries designed specifically for hill mynas.

They also hope to educate the community, to turn its love of captive birds into one that also supports wild populations.

“There is a distinct lack of bird song on Simeulue, especially within close to medium proximity of [human] habitation,” says Amey. “Our ambition is to bring the beautiful sounds of songbirds back to Simeulue’s forests and culture. Songbirds have played an important role in Simeulue culture and many members of the community wish to see them return.”

As with everything in the past year, progress to protect Asian songbirds has slowed down of late. “Unfortunately, the COVID crisis has been a huge, but legitimate, distraction from the global fight against extinction, and very little attention has been paid to such issues in the last few months,” says Rheindt.

Once the pandemic recedes, Shepherd suggests that tourism may play an important role in keeping birds alive, uncaged and in their natural habitats.

“There’s a very big birdwatching community,” he says, “and I think working with the community and with the birdwatching tour guides to raise awareness of the benefits of having songbirds around is important. The birdwatching industry’s worth millions. I think we need to raise awareness of the fact that you can lose your birds, but also awareness of the facts that having birds around is good for the environment, it’s good for your mental health, it’s good for all kinds of things — but it’s good for the economy.”

Until those messages resonate more than the ka-ching of a cash register, however, Asian songbirds will remain in crisis.

Reposted with permission from The Revelator.

- What Does the World Need to Understand About Wildlife Trafficking ...

- Brazilian Amazon Has Lost Millions of Wild Animals to Criminal ...

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe