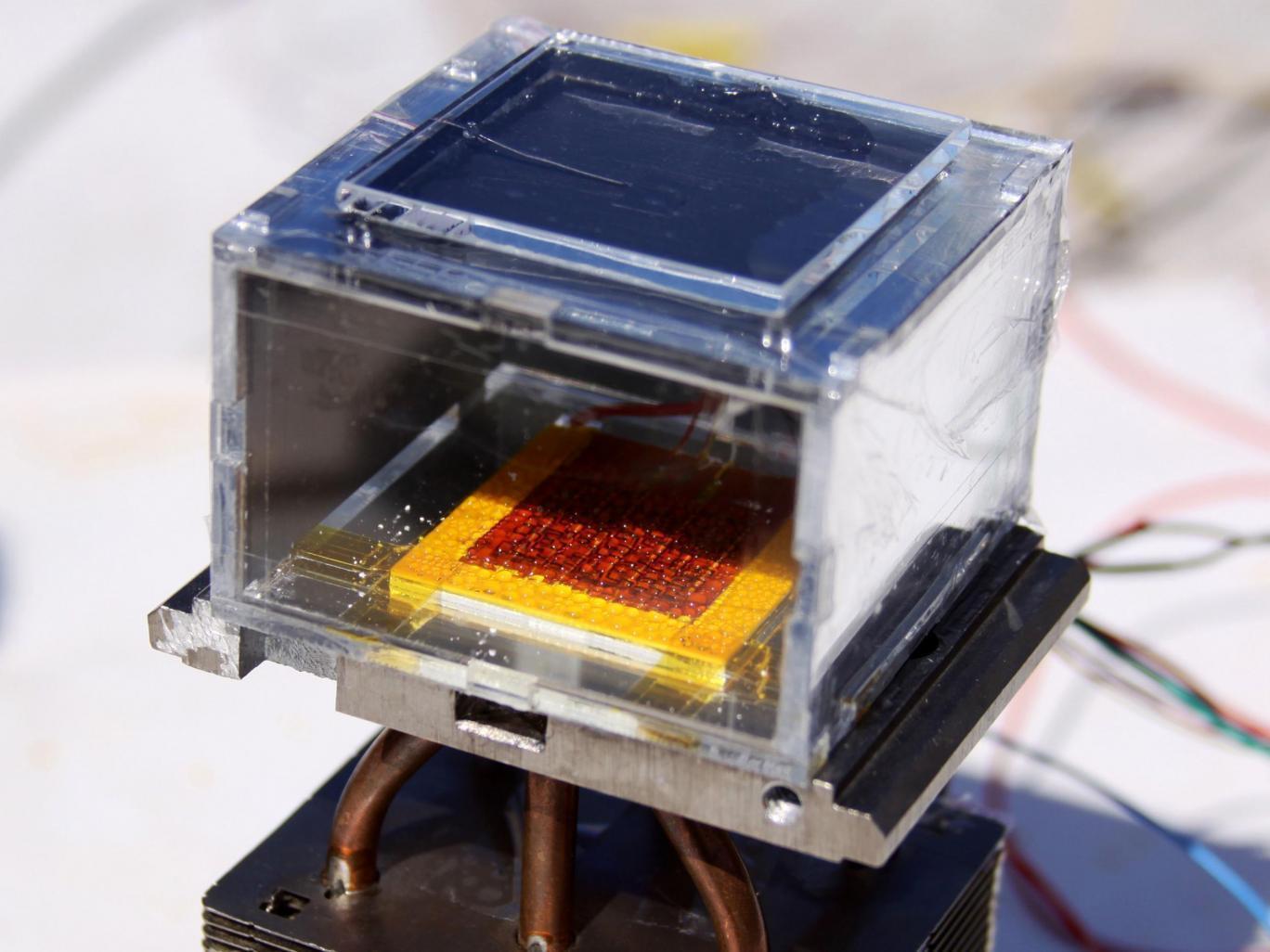

This device can pull liters of water from arid air. Photo credit: MIT photo from laboratory of Evelyn Wang

As a worldwide water crisis looms, engineers have invented a solar-powered harvester that can pull water out of thin air—even in dry, desert environments.

A team from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the University of California, Berkeley have created a device using a specially designed metal-organic framework (MOF) capable of pulling liters of water in conditions where humidity is as low as 20 percent, a level common in arid areas. Impressively, it only needs the power of the sun to operate.

This breakthrough was published in a paper Thursday in the journal Science.

There are already dehumidifiers and other products out there that can collect water from humid air. The process, however, can be energy-intensive and essentially leave you with “very expensive water,” as senior author Omar Yaghi of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory put it in a statement.

The new device, however, “is capable of harvesting 2.8 liters of water per kilogram of MOF daily at relative humidity levels as low as 20 percent, and requires no additional input of energy,” the authors state in their paper. That’s about 2.8 liters of water in 12 hours.

“We wanted to demonstrate that if you are cut off somewhere in the desert, you could survive because of this device,” Yaghi said. “A person needs about a Coke can of water per day. That is something one could collect in less than an hour with this system.”

The Berkeley professor invented metal-organic frameworks more than 20 years ago. MOFs combine metals such as magnesium or aluminum with organic molecules to form rigid, porous structures that can store gases and liquids. More than 20,000 different MOFs have been created by researchers worldwide.

According to a news release, here’s how this new solar-powered, water-collecting MOF works:

In 2014, Yaghi and his UC Berkeley team synthesized a MOF—a combination of zirconium metal and adipic acid—that binds water vapor, and he suggested to Evelyn Wang, a mechanical engineer at MIT, that they join forces to turn the MOF into a water-collecting system.

The system Wang and her students designed consisted of more than two pounds of dust-sized MOF crystals compressed between a solar absorber and a condenser plate, placed inside a chamber open to the air. As ambient air diffuses through the porous MOF, water molecules preferentially attach to the interior surfaces. X-ray diffraction studies have shown that the water vapor molecules often gather in groups of eight to form cubes.

Sunlight entering through a window heats up the MOF and drives the bound water toward the condenser, which is at the temperature of the outside air. The vapor condenses as liquid water and drips into a collector.

When two-thirds of the world’s population is experiencing water shortages, the water vapor and droplets in the atmosphere—estimated to be around 13,000 trillion liters—is a natural resource that could address the global water problem, the authors explained in Science.

The team noted that their harvester is proof of concept and has room for improvement. The current device can absorb only 20 percent of its weight in water. They hope to double that amount or tweak the invention so that it can be more effective at higher or lower humidity levels.

Still, as Yaghi pointed out, “this is a major breakthrough.” This invention could enable people to have an off-grid water supply.”

“One vision for the future is to have water off-grid, where you have a device at home running on ambient solar for delivering water that satisfies the needs of a household,” Yaghi said. “To me, that will be made possible because of this experiment. I call it personalized water.”

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe