There Are 68.4 Million Better Places for Solar Panels Than Mr. Trump’s Wall

SolarWorld

By John Rogers

President Trump on Tuesday suggested putting solar panels on his infamous border wall to help pay for it (since Mexico certainly won’t). While there are more things wrong with that proposal than I can cover in this space, it’s great to see that President Trump has finally figured out solar panels are cost-effective energy investments, paying for themselves even if you ignore the many environmental benefits. But here are more than 68.4 million better places for President Trump to invest in solar to pay dividends for the American people.

Solar on the roof

The U.S. National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) last year published a fine study of the potential of America’s rooftops to host solar. The researchers analyzed how much solar photovoltaic (PV) capacity we could get overhead, from existing buildings (considering roof orientation, tilt and shading), and calculated what it would add up to.

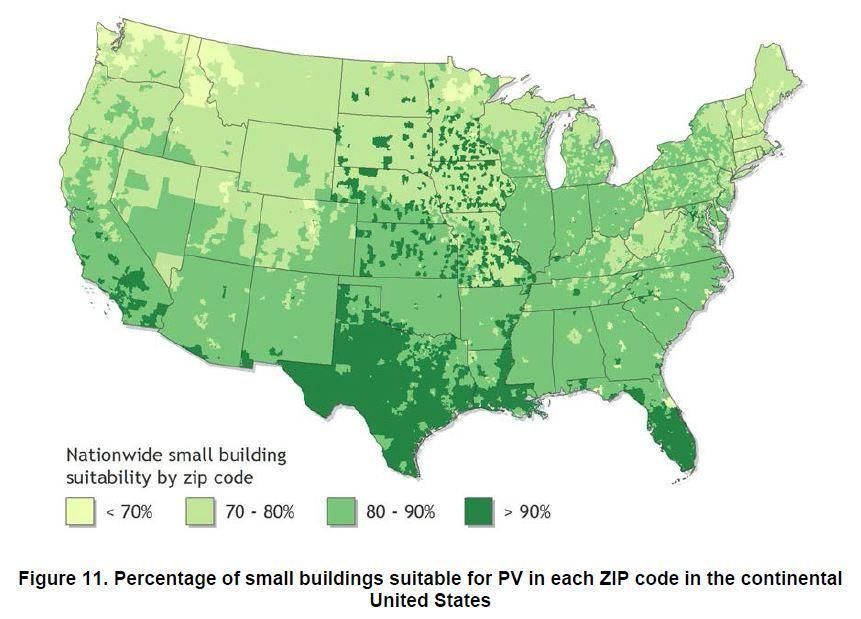

One conclusion of that analysis was that “83 percent of small buildings have a suitable PV installation location,” and that more than a quarter of the total roof area of those buildings could work. NREL is careful to say that that’s the technical potential, not necessarily what would make sense in other regards. But if we take that 83 percent, and consider the number of stand-alone, single-family houses, you end up with 68,380,764 million (give or take a few million) places to put solar.

As it happens, a lot of those sunny rooftops are near our beautiful southern border: In most Texas zip codes, for example, more than 90 percent of the small buildings might work for solar.

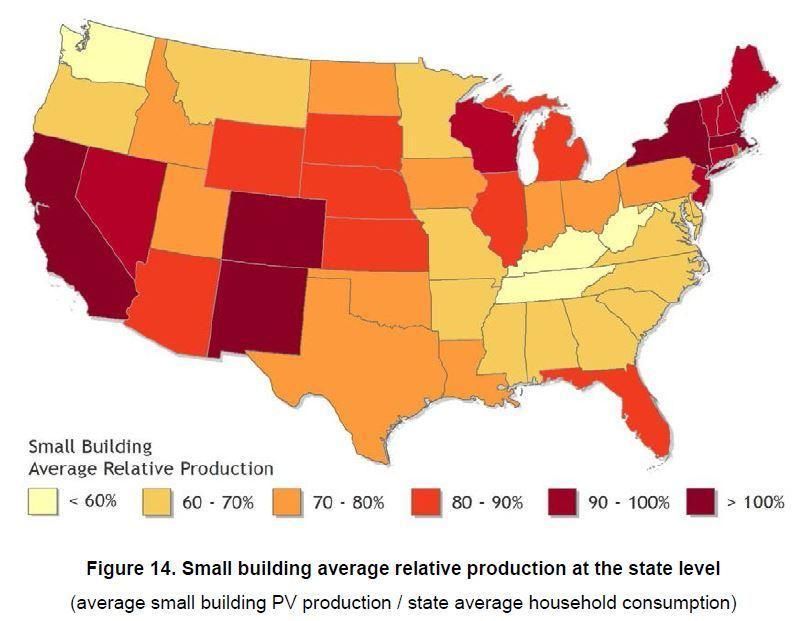

From a technical potential point of view, residential rooftops across the country could meet a big chunk of household electricity needs in a lot of states: More than 90 percent in a dozen states, and at least 70 percent in 27 states.

Solar on more roofs

But wait, there’s still more: Note that NREL’s “small buildings” doesn’t just mean detached single-family homes. If we add in duplexes and small apartment buildings, that would mean millions more rooftops for solarizing.

And then there’s plenty of roof space beyond small buildings: commercial, industrial and institutional roofs. NREL found that “more than 99 percent of large and medium buildings” have some place that would work for solar (“at least one qualifying roof plane”). And the total rooftop area that would work is much higher than for small buildings (very few trees shading the middle of a big-box store roof…). Their calculations suggest potential on around half of the total roof area of medium buildings, and two-thirds of large ones.

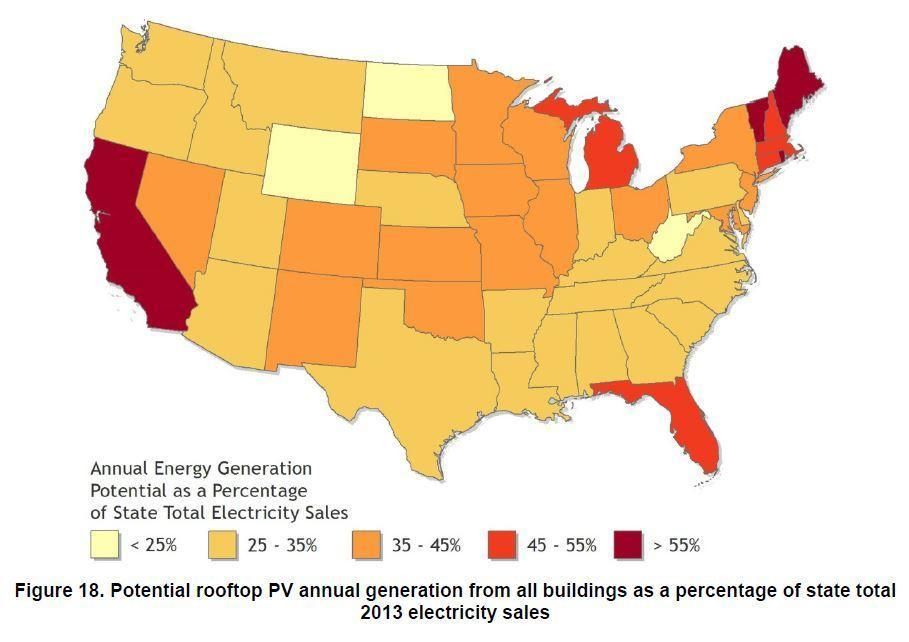

If you take the rooftop potential across the various size buildings (which, unlike walls in the middle of deserts, are already connected to the electricity grid), and compare it even to the total electricity needs in each state, you find that it really adds up (particularly in states and cities that are serious about energy efficiency).

Solar on the ground

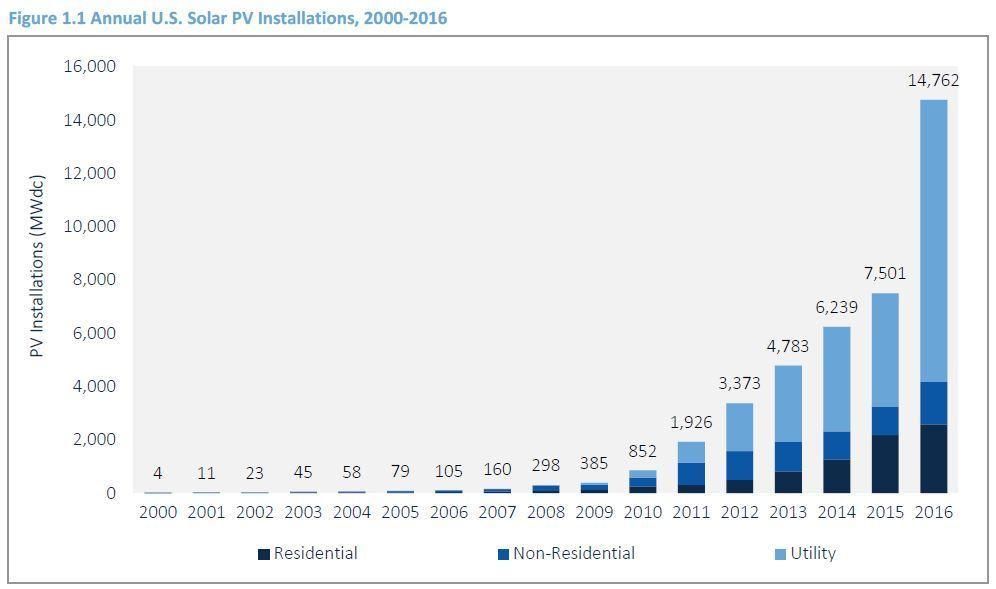

Plus, roofs are definitely not the only place suitable for solar. The latest solar stats show that the progress of large-scale solar, done by utilities and others, has been even more impressive than residential and commercial (“non-residential”).

And large, ground-mounted solar arrays don’t just make sense in fields, farmlands and deserts. Old landfills or “brownfields”—lands that have been degraded by past industrial activity—can be a great fit for new solar capacity. (The same could be true for solar at old power plant sites, where the plants have shut down but the infrastructure and grid connection are still there.)

Larger arrays can also be the foundation of community solar systems, a way of making solar work for people who can’t or don’t want to do it on the roof.

Solar in reality

So enough of the frivolous flights of folly in trying to use solar’s overwhelming popularity to make a wildly unpopular project slightly less unpopular. A border wall might need solar, but solar certainly doesn’t need a border wall.

Solar is real, and it makes sense. And we already have plenty of places to put it, if President Trump would just put his office and budget to good use for moving American energy forward.

John Rogers is a senior energy analyst with expertise in renewable energy and energy efficiency technologies and policies at the Union of Concerned Scientists.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe