Could a 150-Year-Old Fishery Management Practice Do More Harm Than Good?

Why you can trust us

Why you can trust us

Founded in 2005 as an Ohio-based environmental newspaper, EcoWatch is a digital platform dedicated to publishing quality, science-based content on environmental issues, causes, and solutions.

It may seem like good conservation practice to bolster threatened and key commercial populations of native fish by breeding them in captivity and releasing them into the wild. In fact, it has been standard practice for natural resource managers and fisheries for 150 years, according to a press release from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNC Greensboro).

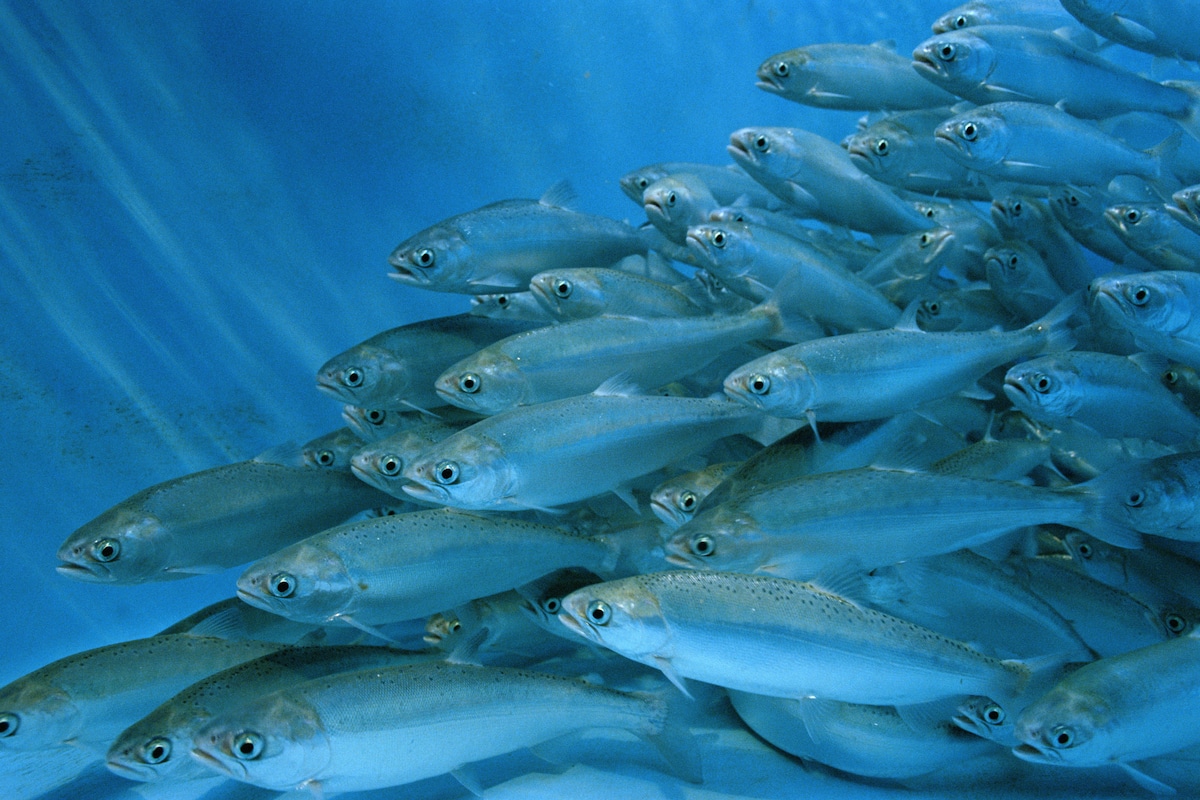

The numbers of captive-bred salmon released into the wild each year are staggering. In 2016, more than two billion hatchery-raised Pacific salmon were released in the U.S.

Considering how common the practice is, what if releasing hatchery salmon into the wild was doing more harm than good?

Recently, scientists from UNC Greensboro published a study that found that the age-old fishery management method provides minimal benefit and actually damages the target species, and has an overall negative impact on ecosystems.

“Many resource managers believe that releasing captive-bred native species into the wild is always a good thing,” said UNC Greensboro freshwater ecologist and leader of the study Dr. Akira Terui in the press release. “However, ecosystems are delicately balanced with regards to resource availability, and releasing large numbers of new individuals can disrupt that. Imagine moving 100 people into a studio apartment — that’s not a sustainable situation.”

The study, “Intentional release of native species undermines ecological stability,” was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“There is a belief that release programs are economically/ecologically beneficial because ‘release’ intuitively helps populations. This strong belief hindered the objective assessment of how hatchery releases impact ecosystems. However, ecosystems have a limited capacity to support species. If we release individuals beyond this capacity, it may harm the ecosystem,” Terui told EcoWatch in an email.

In order to predict how mass releases of captive-bred fish influence wild species, the scientists used mathematical modeling. They used more than two decades of stream monitoring data from 97 Japanese rivers to test and confirm their projections.

“In an ecosystem, the balance that allows different species of fish with similar needs to co-exist is fragile,” said Terui in the press release. “When there is a massive release of members of one species in an ecosystem without the capacity to support them, then the other species populations decline due to greater competition for resources.”

The research team discovered that the release of the captive-bred fish adversely affected the native species. Terui said studies over the past 20 years demonstrated that the fish being released into the wild are genetically different from the wild species and spread genes that reduce their ability to survive in their natural habitat.

“We found that competition with a vast number of captive-bred members of a species leads to reduced numbers of naturally bred members of the same species. Replacing naturally occurring members of a species with captive-bred individuals has the potential to reduce genetic diversity and reproductive fitness,” Terui said in the press release.

Terui told EcoWatch that captive-bred salmon behave differently from those raised in the wild, which may affect their survival.

“Hatchery individuals have a number of distinct features — for example, hatchery salmon are known to be bold. Such differences are thought to emerge through adaptation to the captive environment,” Terui said. “While there is strong evidence that hatchery fish perform poorly in the wild, the exact mechanisms behind this pattern are still unclear, as far as I can tell. That being said, hatchery fish have a number of characteristics (e.g. behavior) that may reduce survival in the wild. For example, bold hatchery individuals may better compete for food, but they may be vulnerable to predation. This is just an example, and there may be other possibilities too.”

Ecosystems depend on a delicate balance between plant and animal species and their environment, and too many individuals of a particular species can upset that equilibrium.

“If we release hatchery fish into the environment beyond what the ecosystem can support, excessive competition for resources (e.g., food, habitat) may occur within the released species and with other species. This adversely impacts ecosystems,” Terui told EcoWatch.

Terui went on to say that hatcheries should look at whether or not particular ecosystems can support new individuals before releasing them into the wild.

“Hatchery programs should carefully consider the status of the receiving ecosystem. If degraded, it is unlikely that the ecosystem can support released individuals; rather, it will exacerbate the competition for limited resources that are already compromised. In my opinion, hatchery programs are effective in limited situations — we should prioritize the conservation/restoration of the environment so that ecosystems can support healthy and sustainable populations,” Terui said.

The research team found that when hatchery salmon were released into the wild, over time the native fish had more population density fluctuations and fewer species in general. Such population instability increases the likelihood that some populations will completely disappear.

“The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is currently spending hundreds of millions of dollars a year on fish hatcheries. Natural resource managers need to be considering alternate priorities like habitat conservation,” Terui said in the press release.

One way to increase wild fish populations without mass releases of hatchery fish is by removing dams that cut them off from their natural habitats.

“Dam removal may help increase fish populations. Many rivers are severely fragmented, with limited access to potential habitats in a watershed. Increasing access to potential habitats may be a powerful tool to increase the sustainability of fisheries and biodiversity conservation,” Terui told EcoWatch.

Subscribe to get exclusive updates in our daily newsletter!

By signing up, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy & to receive electronic communications from EcoWatch Media Group, which may include marketing promotions, advertisements and sponsored content.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe