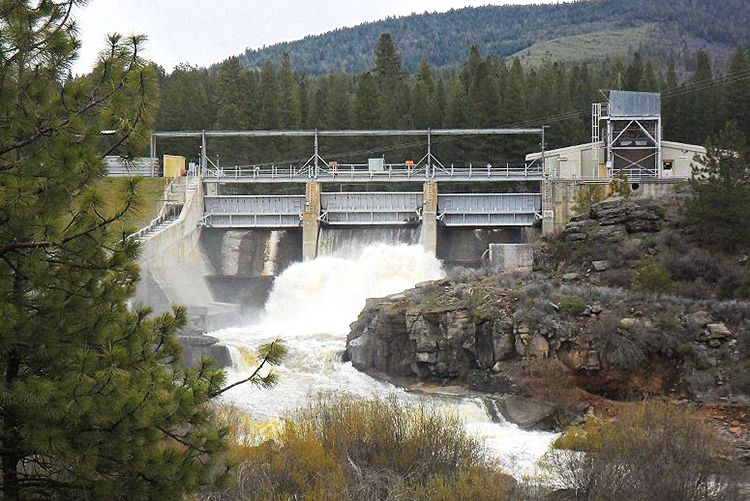

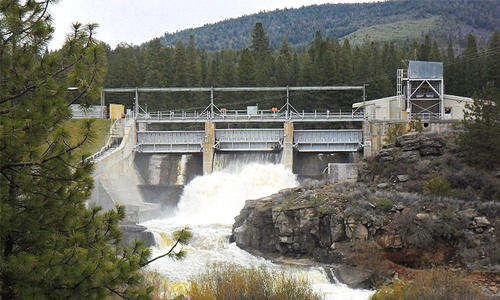

Removal of 4 Dams to Reopen 420 Miles of Historic Salmon Habitat on Klamath River

It’s been 115 years since the first of six dams began regulating flows on the Klamath River, which runs from the high desert of eastern Oregon to the northern California coast.

By 2020 most of them will be gone—and the river’s once-abundant salmon runs hopefully on the rebound—if two new agreements between tribal, state and federal governments, the operator and other stakeholders work out as planned.

Dam removal on the @klamathriver will reopen 420 miles of historic fish habitat. #UnDamTheKlamath pic.twitter.com/TdkrJYkDkS

— Marc Yaggi (@marcyaggi) April 6, 2016

On Wednesday, standing before the mouth of the Klamath River on the Yurok Reservation in California, Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell announced that the federal departments of the interior and commerce, along with the states of Oregon and California and the Karuk and Yurok tribes, have signed a new agreement with electric power company PacifiCorp to decommission and remove four hydropower dams along the Klamath River.

The agreement creates a “path forward for the largest river restoration in the history of the United States,” along with “the largest dam removal project in the history of our nation,” Jewell said.

The new pact will allow PacifiCorp to take three dams in California—Copco 1, Copco 2 and the Iron Gate Dam—and the John C. Boyle Dam in Oregon out of service by using the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s established licensing process for hydropower.

PacifiCorp’s license to operate the dams expired in 2006. An earlier agreement to authorize their removal, created in 2010, required Congressional approval and expired at the end of 2015 after Congress adjourned without enacting it.

“From the company’s point of view, we have the same agreement [today] that we negotiated since 2008,” said Bob Gravely, a spokesperson for PacifiCorp. “This is simply a way to continue pursuing it without needing involvement from Congress.”

The second agreement commits the state and federal governments to assisting farmers and ranchers in the river’s upper basin with the likely financial and regulatory impacts of returning fish runs, which will need to be protected from irrigation infrastructure.

While the Klamath River’s runs of spring and fall Chinook salmon have not been formally declared endangered, they have been faltering for years. And since 1997, the Klamath River run of coho salmon has been listed as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act.

This year’s salmon runs are expected to hit historic lows, as drought and the impacts of climate change intensify the effects of poor river conditions created by the dams.

“By removing dams we’re reopening hundreds of miles of spawning habitat and dramatically improving water quality,” said Craig Tucker, natural resources policy advocate for the 4,000-member Karuk Tribe of California, which has signed on to the new agreement. “The Karuk, and the Yurok and other people in this basin are salmon people. Their cultures, their economies, their religion, all rely upon the return of the salmon.”

The removal of the four dams will be the necessary first step in restoring the river’s fish habitat, Tucker said, but much more will need to be done, including restoration of marshes and other wetlands in the upper basin.

Lack of salmon has led many Karuk to consume a more Western diet, Tucker said, leading to rates of heart disease, diabetes and obesity in the tribe that outpace national averages. “Historically, research shows that Karuk consumed 1.2 pounds of salmon per person per day. Now we’re lucky if each person gets four pounds a year,” he said.

The absence of the salmon has also harmed the tribe’s religious practices, including one ceremony tied to the arrival of the first spring Chinook. “The spring salmon is probably the most at-risk run of salmon in the river,” Tucker said. “You can’t have that ceremony without salmon.”

Hosts of other important ceremonies traditionally “feed everyone with salmon who comes and if there are no fish, they can’t meet that obligation,” Tucker added. “It would be like if the Pope didn’t have enough wine and crackers for mass.”

“We see removal of these dams as the single biggest act of restoration that can be carried out on the Klamath,” Tucker said. “I would assert that it’s the biggest salmon restoration project in U.S. history.”

This article was reposted with permission from our media associate TakePart.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Half of World Heritage Sites at Risk From Fossil Fuel Development and Other Industries

Protecting the Earth Is Not a Crime

Groups Sue FDA Over Approval of Genetically Engineered Salmon

Maryland to Become First State to Ban Bee-Killing Pesticides for Consumer Use

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe