The legacy of U.S. racism has permeated the very air of its cities.

In a textbook example of environmental racisim, a new study from UC Berkeley and the University of Washington (UW) found that neighborhoods subject to discriminatory housing practices nearly 100 years ago still have higher levels of air pollution today.

“Racism from the 1930s, and racist actions by people who are no longer alive, are still influencing inequality in air pollution exposure today,” study co-author and UW civil and environmental engineering professor Julian Marshall told UW News. “The problems underlying environmental inequality by race are larger than any one city or political administration. We need solutions that match the scale of the problem.”

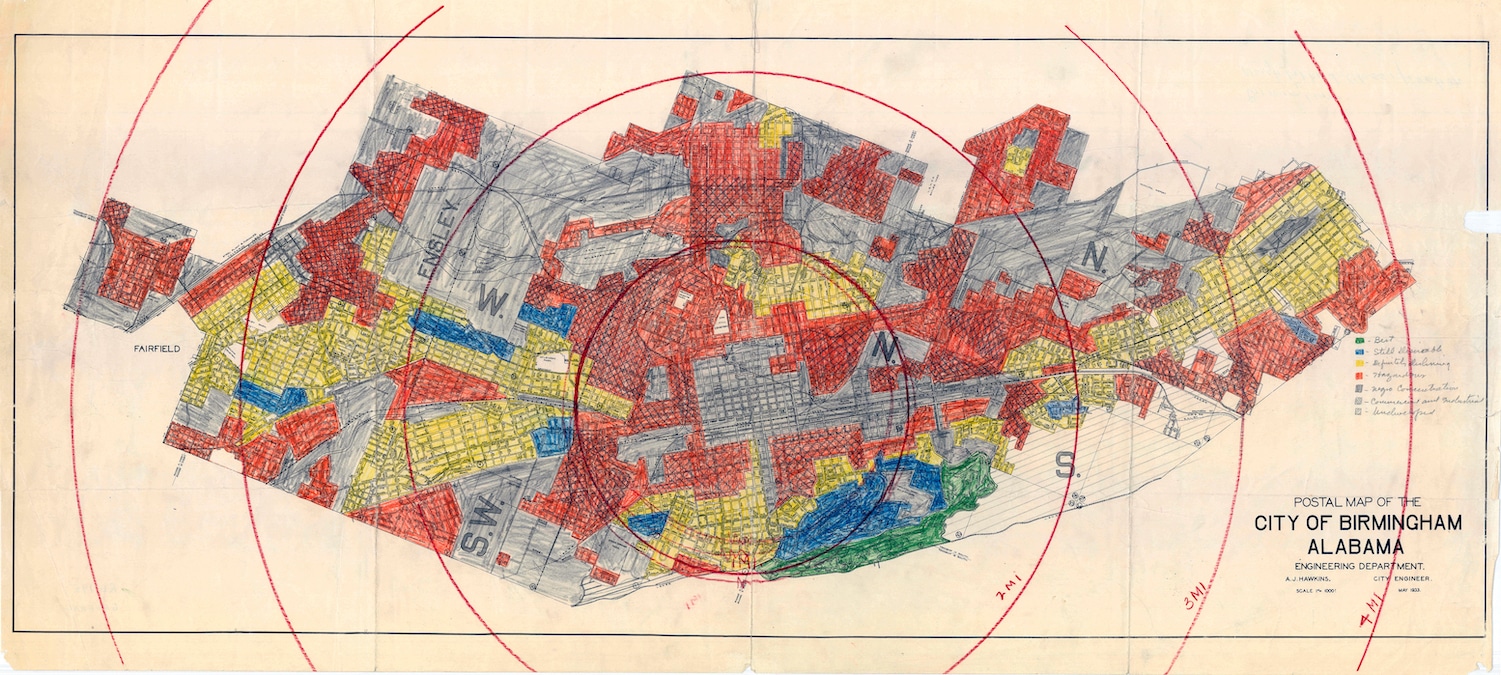

The research, published in Environmental Science & Technology Letters Wednesday, was the first to compare contemporary urban air pollution with redlining. Redlining was the historical practice of assigning higher risk to neighborhoods with high percentages of Black, Asian, working class or immigrant residents. These areas were labeled “red” and deemed bad investments. People who lived in these areas consequently had a harder time accessing loans and mortgages, and therefore the neighborhoods had low home ownership rates and few economic opportunities.

This process was supported by the federal government and enshrined in maps created by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation between 1935 and 1940, according to The Guardian. The maps ranked neighborhoods from A for white majority to D for majority non-white, The Washington Post explained. Many of the D-grade or redlined neighborhoods ended up hosting polluters like industrial plants, highways or ports.

The researchers looked at these maps and compared the historical grade of neighborhoods in 202 U.S. cities with their 2010 levels of nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter air pollution as well as 2010 census demographics, the study authors explained. They found that neighborhoods awarded lower grades in the past still had higher levels of air pollution today. In historically redlined areas, there was more than 50 percent more nitrogen dioxide pollution than in “A” neighborhoods.

While redlining was outlawed more than 50 years ago, the study proves that its impacts are still being felt today and builds on previous research finding that people of color in the U.S. are more likely to be exposed to environmental hazards including air pollution. Marshall was also involved with a study published in December 2021 that found that people of color in the U.S. were more likely to breathe in six different air pollutants, for example.

This is especially concerning because air pollution is a major public health issue that causes ailments like asthma, heart disease and stroke.

“If you just look at the number of people that get killed by air pollution, it’s arguably the most important environmental health issue in the country,” study co-author and UC Berkeley School of Public Health assistant professor Joshua Apte told The Washington Post.

The study authors found that urban air pollution levels were more strongly associated with redlining status than with race and ethnicity, according to the UW News.

The results “emphasized the importance of identifying and improving conditions in those neighborhoods which have been systematically isolated from financial investment through practices like redlining while being subjected to increased environmental exposures for decades,” study lead author and UC Berkeley doctoral student in civil and environmental engineering Haley Lane told UW News.

At the same time, people of color who live in formerly redlined areas still have more pollution exposure than white people who live in the same neighborhoods.

“Redlining is a good predictor of air pollution disparities but it’s only one of the things that drive the racial and ethnic disparities in air pollution. It’s not the only source of disparity that we need to be worried about,” Apte told UW News.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe