Pexels

By Martin Kuebler

Pulses, a broad category of edible seeds that includes pantry staples like lentils, beans, peas and chickpeas, are one of the world’s most important food crops.

This underrated legume has featured heavily in diets around the world for thousands of years. Pulses are the main source of protein for people who don’t eat meat — whether by choice or by circumstance — they’re good for the environment, nutritious and tasty.

Environmentally Friendly Meat Alternative

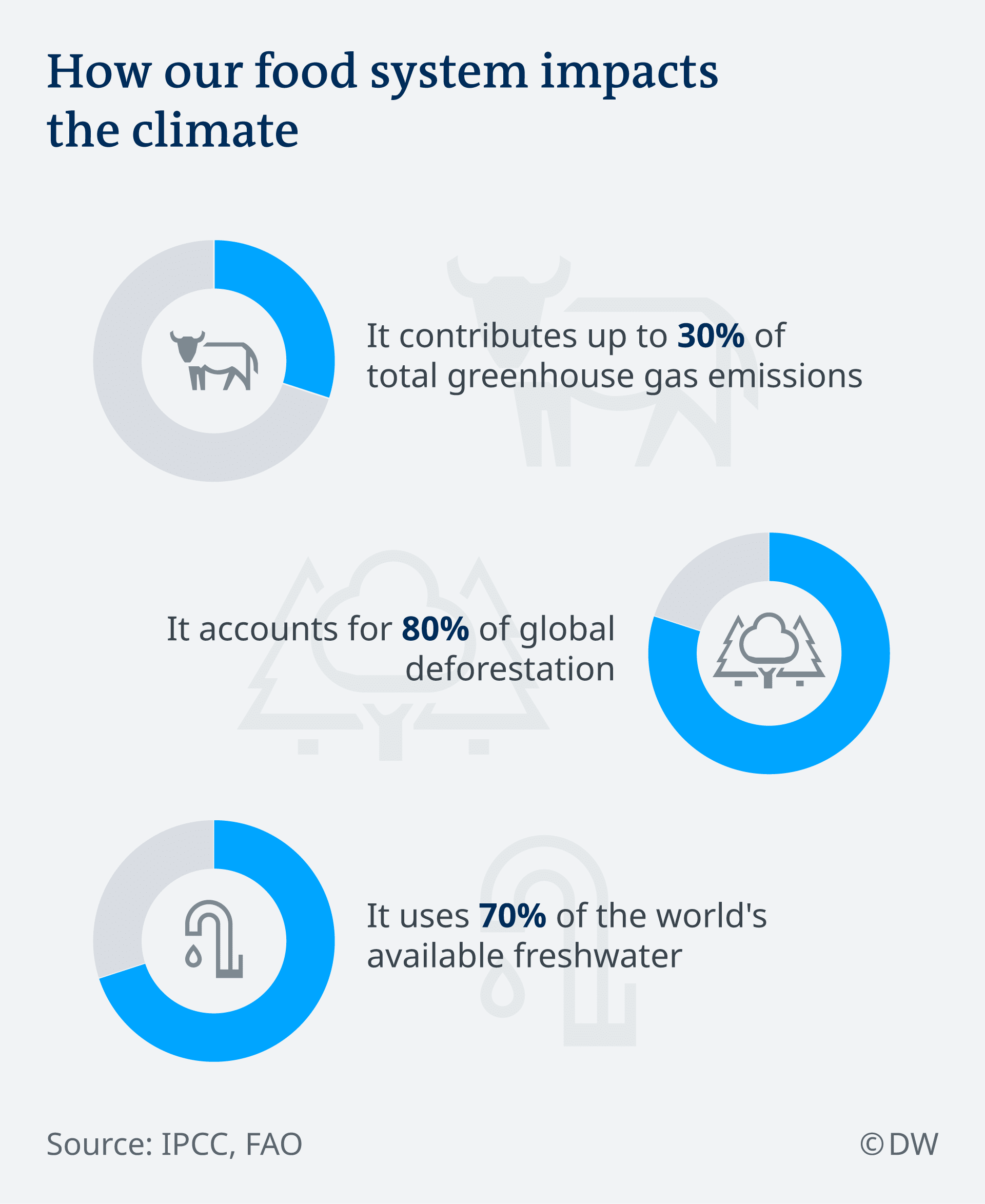

Changing our diet, and how we produce what we eat, can have a huge and positive impact on the planet.

A recent key report on food and biodiversity loss linked global eating habits to around 30% of human-made emissions in terms of energy and fertilizer, making them a “key driver of climate change.” It also highlighted the devastating impact of our food production on nature.

A big part of the problem is meat and other animal products. Though it might be a good source of protein, meat is terrible for the environment. Getting a kilogram of beef to your kitchen emits as much as 60 kilograms (130 pounds) of CO2-equivalent, according to a 2018 study published in Science. And with the world population set to surpass 10 billion in a little over 30 years, increasing demand for food — especially meat and monocrops like wheat, corn and soybeans — will further stress the climate, limited natural resources and biodiversity.

Pulses like peas and lentils, however, produce some 0.9 kg of CO2-equivalent for every kilo grown. And they provide a far higher protein yield per square kilometer than a herd of cattle or flock of chickens, meaning existing farmland can be used more efficiently and untouched forests can be spared.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has promoted pulses as “a good alternative to meat,” pointing out that they “can play a key role in future healthy and sustainable diets.” In recent years, calls from environmental groups for people in the Western world to drastically reduce their meat consumption, has inspired a growing trend toward vegetarian and vegan diets.

In a September analysis, climate data provider Carbon Brief said “a global switch to veganism would deliver the largest emissions savings out of any dietary shift,” preventing some 8 billion metric tons of CO2 emissions annually by 2050. Current food production is responsible for around 13.7 billion tons per year.

“It is now becoming clear that a plant-based diet is not just a crock,” said Christina Ledermann, head of the German advocacy group Humans for Animal Rights. “The future of nutrition is plant-based, or there is no future.”

Pulses Enrich Soils, Save Water

Pulse crops are very efficient when it comes to capturing existing carbon from the air and storing it in the soil. One analysis suggested that legumes can store 30% more carbon than other plant species due to their ability to fix nitrogen in the soil via root nodules.

These nodules, which are formed by rhizobia bacteria attached to the roots, absorb inert nitrogen from the soil. This symbiotic relationship helps increase microbial biomass and improve soil biodiversity, while also providing plants with nutrients and energy.

Nitrogen, along with phosphorus, potassium, sulfur, calcium and magnesium, is one of the key macronutrients found in soil. And according to estimates by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 190 million hectares (470 million acres) of pulse crops contribute to as much as 7 million metric tons of nitrogen in soils around the world every year.

This naturally produced fertilizer results in higher yields for pulses and other crops and implies a lesser need for polluting organic and synthetic chemical fertilizers, reducing direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions and preventing further contamination of soils and waterways. Bean crop residue — stalks, leaves and seed pods — can also be used as fertilizer, or as fodder for livestock.

Beans also get by with much less water, making them ideal crops for regions prone to drought. The FAO has estimated that growing a kilo of lentils requires around a third less water than a kilo of chicken, and just a tenth less water than a kilo of beef. Some pulses like pea and lentils also rely more heavily on rain and other surface moisture for their water needs, leaving more groundwater available down below for future crops.

Healthy Way to Improve Food Security

Pulses make up 75% of the average diet in developing countries. Countries in South Asia, especially India, are famed for their extensive use of pulses — which are also very healthy. Besides being an excellent source of protein, pulses are also high in fiber, have little fat and no cholesterol.

The FAO devoted an entire year to pulses in 2016 to raise awareness about how important the likes of lentils, beans, peas and chickpeas are for billions of people around the world. And over the last decade, new seed varieties developed by programs like the Tropical Legumes initiative have made high-yield, climate-resilient pulses an increasingly important crop for smallholder farmers.

Pulses such as chickpeas and lentils are a key component of agricultural practices like intercropping, which help regenerate soils and foster the growth of other non-pulse crops. Planting them in rotation with other plants also helps ward off certain pests and diseases that only affect specific species.

Reposted with permission from Deutsche Welle.

- World Must Reach 'Peak Meat' by 2030 to Fight Climate Crisis ...

- 15 Best Protein Alternatives to Meat Besides Tofu - EcoWatch

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe