Taking on Climate Change and Petrochemicals in the Ohio River Valley

When it comes to the fossil fuel industry, we’ve all heard the promises before: new jobs, economic growth and happier communities, all thanks to their generosity and entrepreneurial spirit.

If you’re struggling or there aren’t a whole lot of other options for work, it can all sound glowing and great.

But what they always fail to mention is that their business damages ecosystems, drives climate change, and fills our air and water with dangerous, carcinogenic chemicals. Which all have a way of transforming lives and communities for the long-term and in ways that don’t exactly make great PR.

We know this because we’ve seen the same tragic story again and again: fossil fuels and petrochemicals causing disastrous health outcomes for normal Americans just trying to live their lives.

In particular, in southern Louisiana along an 85-mile corridor of the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, petrochemical plants are causing some of the nation’s highest cancer rates. There are important lessons to be learned from this area, infamously dubbed “Cancer Alley.” Especially as the fossil fuel industry plans to invest more than $200 billion in new petrochemical facilities across the U.S. in the coming years.

To understand this issue, it’s worth a quick recap on petrochemicals and the problems they create. What are petrochemicals, how are they used, and what problems can they cause? Read on for answers.

The Truth About Petrochemicals

Put simply, the term “petrochemical” encompasses several different chemical compounds derived from fossil fuels, most commonly oil and natural gas. These chemicals are produced by applying extreme temperatures and pressures to the fossil fuel used in order to extract them. How extreme? We’re talking temperatures of over 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit and pressures of over 1,000 pounds per square inch (PSI).

And what is all this heat and pressure for? In essence, petrochemicals are used to create plastics, dyes, fertilizers and other synthetic compounds for various industries.

You may be asking yourself, “So what? What’s the big deal here? Why do I need to worry about all this stuff?”

The answer is simple: If you’re concerned about climate change and human health, you need to worry about petrochemicals.

The truth is, there’s no way to produce these compounds without burning an incredible amount of fossil fuels. More investment in petrochemical facilities means more climate change from multiple sources, and critically, more plastics.

Today, a lot of petrochemical investment is going into to building multiple ethane cracker plants. These plants separate ethane from natural gas through the heat and pressure process described above. Plants then use it to create ethylene, one of the major building blocks used in making plastics. Not only does this process involve burning fossil fuels, but the end result is another kind of pollution.

Increasing investment in these facilities will not only deepen our reliance on fossil fuels; it’ll also increase the amount of plastics that end up in our oceans—at a time when we should instead be concentrating on alternatives like clean energy.

Yet, the petrochemical and fossil fuel industries keep finding ways to lock us into their products and business. And the story only gets more frustrating from there. Because beyond even the threat they pose to our climate and the future health of the planet, petrochemical facilities are a significant danger to human health.

We already know the threats to regional watersheds from hydraulic fracturing (fracking), including soil erosion, groundwater pollution, and drinking water contamination. But we should also recognize that the danger doesn’t stop once natural gas leaves the ground. For example, multiple studies have shown that petrochemical facilities that use natural gas expose employees—as well as surrounding communities—to multiple toxins that are incredibly damaging to their health.

The results are clear. Research shows that people living and working in and near petrochemical facilities can have higher rates of cancer, diabetes, various skin conditions, respiratory problems and other life-altering diseases. In some cases, rates of toxic chemicals and carcinogens found among people living by plants have been as high as three times the national average.

So, what can we learn from all of this beyond the fact that this industry is bad for our bodies and our planet? Here are a few key takeaways:

1. The Industry Knows It’s Causing Harm

In multiple communities along Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley,” these problems have gotten so big that the petrochemical industry has issued buyouts for residents’ homes. In some ways that could sound like a kind of victory, as families may have the ability to relocate. But what we know is that the damages caused have been so significant that, even if they move, people will likely be dealing with ongoing health issues for the rest of their lives.

Moreover, as their friends, neighbors, and relatives have gotten sick and even died, people in Cancer Alley and similar areas are left dealing with not only a loss of life, but also, the loss of community. Even so, the interests behind petrochemical investment keep pushing forward. With one hand they offer a too-late “solution,” and with the other, ever-more money to keep harming people and the planet.

2. These Damages Can Be Exacerbated by Natural Disasters Such as Floods

If it’s not bad enough that these facilities release dangerous pollutants, some plants are also creating “pollution dumps” following major rainfall events storms and floods, putting surrounding communities at even greater risk.

During power outages or flooding at plants, some safety features may turn off without warning. If operations are not shut down quickly or efficiently enough, the result can be increased pollutants entering the air. Plus, flooding can wash even more pollution into nearby lakes, rivers, and even groundwater.

And as climate change has actually been shown to make storms more frequent and severe, these risks will likely only get worse as time goes on.

3. There’s Legal Precedent for Fighting Fracking

All of his sounds terrible, we know, but we do have some good news. The (super) simple version of how fracking works is that companies force chemicals into the ground at such high pressures that it cracks the Earth’s crust, releasing gas trapped below. Companies can only frack on land where they own the legal right to what’s under the ground (known as “mineral rights”). The danger is that the cracks they make can spread and allow toxic chemicals to leach into soil and groundwater far beyond the fracking site.

Now the good news. In a recent court decision, Pennsylvania judges ruled that companies have to contain these cracks to avoid trespassing on other properties where they do not possess mineral rights. This sets a powerful precedent to make the case that mineral rights in one area should not mean that fracking companies and their partners can pollute or alter ecosystems with abandon. More importantly, this victory in the courts should increase momentum for other legal action against polluters and the broader fossil fuel industry.

4. Organized Communities Have the Power to Fight Back

Here’s an infuriating fact: the fossil fuel industry often actively seeks to work in poorer communities because they know wealthier ones have the resources and will to fight them. The wealthy interests behind these investments don’t want these toxic chemicals in their own backyard – but yours will do just fine.

Environmental injustice has a long history in this country. Chemical plants and other toxic facilities have always been built in modest-income communities and, especially, communities of color.

But there’s good news here too.

You see, we know that there is power in community action. When people stand together and work across boundaries to fight for change, their collective action can be a powerful force. Those buyouts we described in Cancer Alley? They happened because people in those communities joined forces to fight together for compensation.

Communities all over that 85-mile stretch of Louisiana are still fighting the good fight. They’re calling for reductions in emissions, mandatory monitoring systems, and improved safety features and management.

Change is hard. But it’s also very possible. And we believe this fight is winnable.

Taking on Petrochemicals in the Ohio River Valley

We can’t give up on the fight to clean up the petrochemical corridor of Louisiana. We also can’t ignore the lessons we’ve learned there.

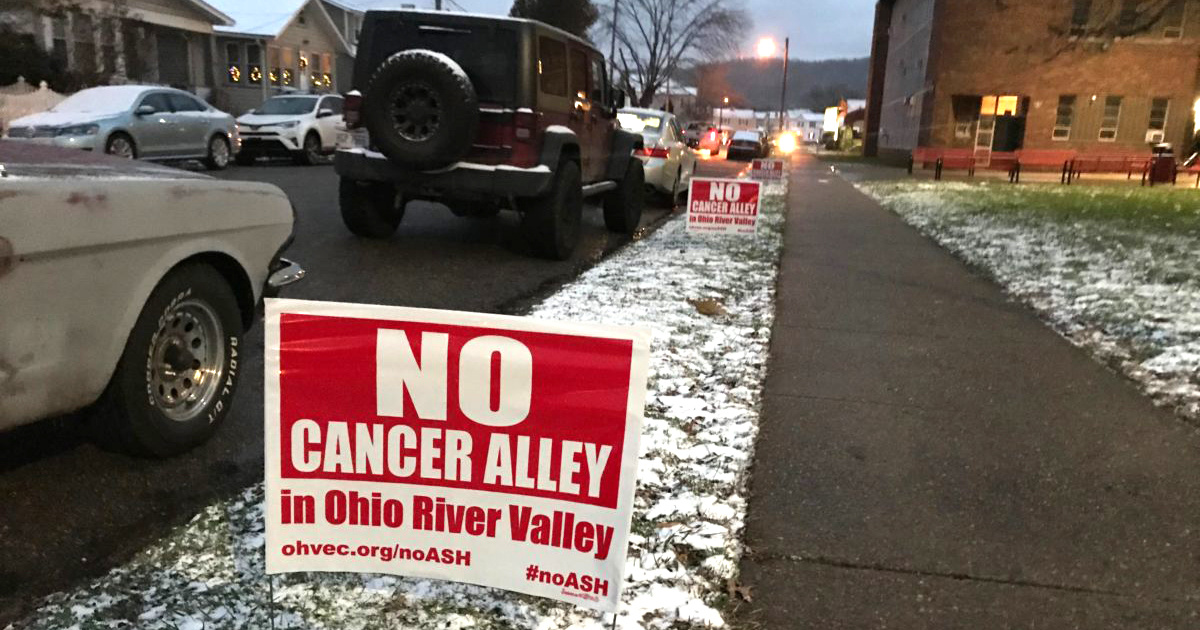

Right now, the petrochemical industry is eyeing the Ohio River Valley—a region spanning southwestern Pennsylvania, eastern Ohio, West Virginia and east Kentucky—as a site for massive investments in new facilities and ethane cracker plants. We can’t let this region turn into a second Cancer Alley.

The fight has already begun. Right now, The Climate Reality Project is mobilizing communities, organizations, activists, and policymakers across the region to stand up to oppose these developments and protect people and our planet.

And if you’re reading this, we need your help!

If you live in the Ohio River Valley, in particular, there are many ways you can take action:

- Join a local Climate Reality chapter;

- Attend one of our upcoming activist trainings;

- Speak up to oppose these plants at a public hearing; or

- Talk to your friends and family about this danger to their health and climate – and share how they can join you in fighting back.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe