Personal Care Products as Dangerous for the Air as Car Exhaust, Study Finds

Rush hour in Boulder, Colorado. Theo Stein / NOAA

People’s efforts to keep themselves clean are actually making the air dirtier, at least in Boulder, Colorado.

A study by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Cooperative Institute for Research In Environmental Sciences (CIRES) found that emissions from personal care products commuters use before leaving in the morning were roughly equivalent in magnitude to emissions from the tailpipes of their cars, a CIRES press release reported Monday.

“We detected a pattern of emissions that coincides with human activity: people apply these products in the morning, leave their homes, and drive to work or school. So emissions spike during commuting hours,” lead author Matthew Coggon, a CIRES scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder, said in the release.

The results are in keeping with an earlier NOAA and CIRES study that found personal care and cleaning products were a major contributor to air pollution in Los Angeles.

“We all have a personal plume, from our cars and our personal care products. It’s likely that emissions from personal care product also affect the air quality in other cities besides Boulder and L.A. Our team wants to learn more about these understudied sources of pollution,” Coggon said.

The results, published April 16 in Environmental Science and Technology, were a bit of a surprise.

In December 2015, February 2016 and January 2017, researchers measured volatile organic compounds (VOC) that react with nitrogen oxide in sunlight to form particulate matter and ozone, two types of air pollution dangerous to human health.

One VOC they measured was benzene, a common car emission used to monitor traffic pollution. But they also found large quantities of an unknown VOC.

“We found a big peak in the data but we didn’t know what it was,” Coggon said in the release.

Then NOAA scientist and study co-author Patrick Veres identified it as siloxane. Since the siloxane peaked at the same time as benzene, researchers hypothesized it was also coming from car exhaust, but when they tested car emissions directly, they couldn’t find it.

But siloxane is also commonly used in personal care products such as shampoo, lotions and deodorants to make them silky and smooth. The researchers realized that siloxane levels peaked with benzene levels in the morning because people were leaving their homes leaving their homes showered and lotioned to drive to work.

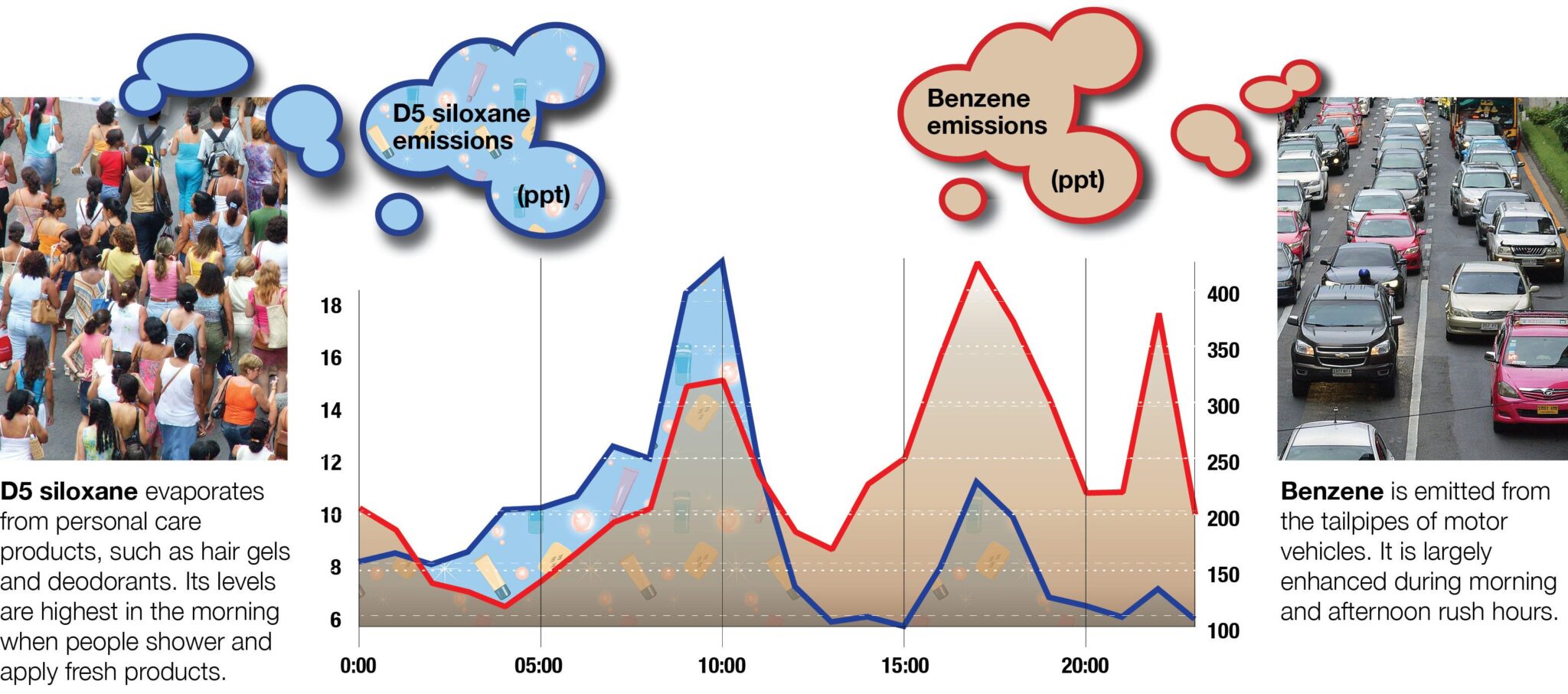

Both decreased during the day and peaked again in the evening, but by then siloxane levels were lower than benzene levels, since much of the compound had already evaporated off of commuters’ bodies and hair.

How siloxane and benzene levels vary throughout the day.Kathy Bogan / CIRES

While the researchers hadn’t set out to look for pollution from personal care products, their findings, as mentioned, connected to a February NOAA and CIRES study that found VOCs released by personal care products, cleaning products, paints and pesticides made up half of the VOCs measured by the researchers in Los Angeles.

The CIRES press release also comes the same day as another study found that U.S. Environmental Protection Agency data had overestimated the decline in U.S. air pollution.

The authors of that study suggested that, as efforts to target transportation and industrial emissions gained headway, other untargeted pollution sources like boilers and off-road vehicles were now playing a bigger role in overall pollution levels.

In his comments on the recent Boulder study, the leader of the Los Angeles study, Brian McDonald, suggested something similar might be taking place with VOCs from personal care products.

“This study provides further evidence that as transportation emissions of VOCs have declined, other sources of VOCs, including from personal care products, are emerging as important contributors to urban air pollution,” McDonald said in the CIRES press release.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe