Researchers from the University of British Columbia say that closing the high seas to fishing could help coastal fisheries, increasing catches by 10 percent. But our waters are now more polluted than ever, threatening the entire food chain.

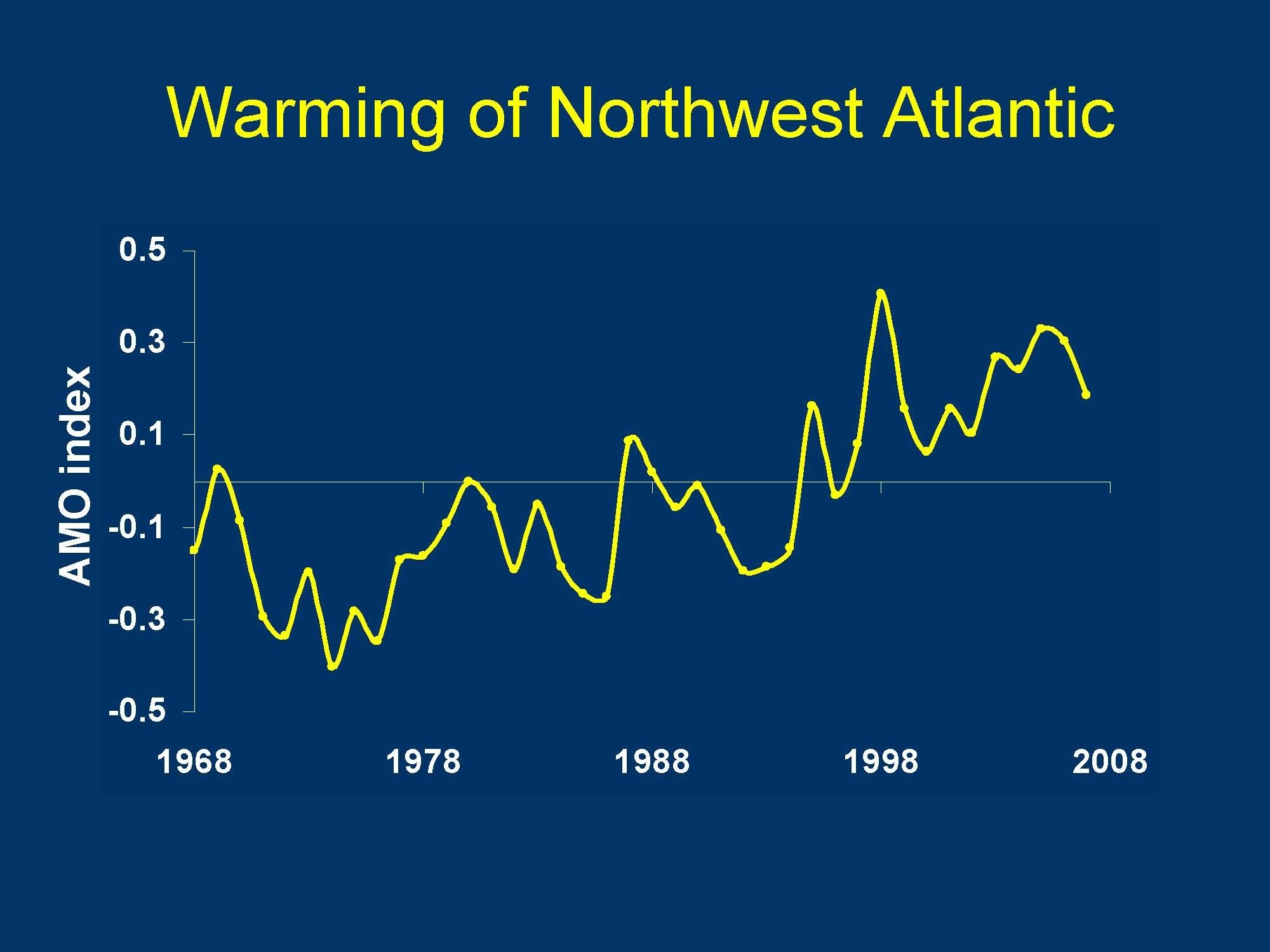

Fish have responded to warming ocean waters by moving north and to deeper waters, and these movements are expected to accelerate. This has resulted in a redistribution of commercial fish stocks. Warm water species are now being found in higher latitudes and tropical water will see “substantial decreases in potential catches” according to the study published Tuesday in Fish and Fisheries. About half of 36 fish stocks in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean have shifted northward in the past 40 years, a 2009 report from the Northeast Fisheries Science Center in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, said.

Similar issues have been seen in coastal fisheries. Maine has been enjoying a boom in lobster fishing as the catch in Southern New England declined from 22 million pounds in 1997 to 3.3 million in 2013. But all is not rosy in the Gulf of Maine, which is warming at the fastest rate of almost any sea. At the Portland Fish Exchange, where 90 percent of Maine’s groundfish catch is sold and stored, annual landings are now averaging 5 to 6 million pounds of cod, flounder, haddock, hake and other species, down from 80 million pounds in the early 1980s.

Climate change is predicted to reduce global catches by 10 percent by 2050, a substantial risk to feed a growing world population. This risk is magnified among island and coastal communities in the tropics, where low income and indigenous communities rely on this key food source.

Uncontrolled and over-fishing has decimated many fish stocks. The Natural Resources Defense Council states that populations of large ocean fish such as tuna and swordfish have declined by 90 percent from pre-industrial levels. The World Wildlife Fund cites poor fisheries management and illegal fishing as key culprits. Just 1.6 percent of the world’s oceans are protected areas, and beyond coastal zones, there are few if any restrictions on commercial fishing. Large, industrial-scale fishing began replacing small operations in the 20th century, rapidly depleting fish stocks. In 1996, at least 86 million metric tons of catch were taken, and perhaps as much as 130 million tons. The total catch has declined ever since. We’ve already past peak fish.

The University of British Columbia looked at 30 key fish stocks against three different modeling scenarios: cooperative international fisheries management, closing the ocean to fishing and maintaining the status quo. Under the status quo, global catches are forecast to decline 5.8 percent by 2050, with a deep-sea drop of 10.9 percent. The take in coastal fisheries, defined as exclusive economic zones (EEZ), declines by 5.5 percent. Under cooperative management, global catches increase by nearly 30 percent while the coastal catch increases 6.3 percent. The most dramatic benefit to coastal zones comes from a closure of deep sea fisheries, with a gain in the EEZs of 10.3 percent. Total global catch under this scenario declines by 3.4 percent.

Unquestionably, there’s a trade-off. The researchers see it this way: “Although the scenario with sustainable high seas fisheries performs best amongst those that we explored, it is important to question the likelihood of achieving effective management of sustainable fisheries in the high seas.”

Gaining full cooperation and enforcement is unlikely. Tropical countries are going to lose out most. High seas closure would help mitigate inequality in fish stock redistribution and enhance resilience of fish species.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe