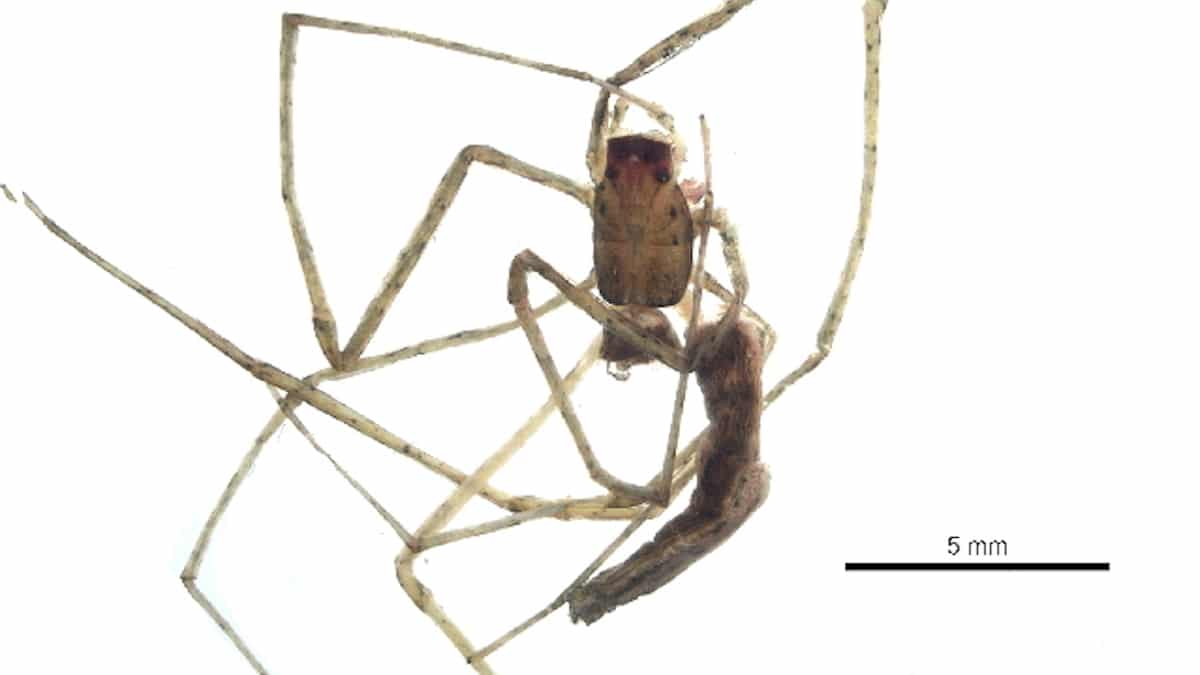

A net-casting ogre-faced spider. CBG Photography Group, Centre for Biodiversity Genomics / CC BY-SA 3.0

Just in time for Halloween, scientists at Cornell University have published some frightening research, especially if you’re an insect!

The ghoulishly named ogre-faced spider can “hear” with its legs and use that ability to catch insects flying behind it, the study published in Current Biology Thursday concluded.

“Spiders are sensitive to airborne sound,” Cornell professor emeritus Dr. Charles Walcott, who was not involved with the study, told the Cornell Chronicle. “That’s the big message really.”

The net-casting, ogre-faced spider (Deinopis spinosa) has a unique hunting strategy, as study coauthor Cornell University postdoctoral researcher Jay Stafstrom explained in a video.

They hunt only at night using a special kind of web: an A-shaped frame made from non-sticky silk that supports a fuzzy rectangle that they hold with their front forelegs and use to trap prey.

They do this in two ways. In a maneuver called a “forward strike,” they pounce down on prey moving beneath them on the ground. This is enabled by their large eyes — the biggest of any spider. These eyes give them 2,000 times the night vision that we have, Science explained.

But the spiders can also perform a move called the “backward strike,” Stafstrom explained, in which they reach their legs behind them and catch insects flying through the air.

“So here comes a flying bug and somehow the spider gets information on the sound direction and its distance. The spiders time the 200-millisecond leap if the fly is within its capture zone – much like an over-the-shoulder catch. The spider gets its prey. They’re accurate,” coauthor Ronald Hoy, the D & D Joslovitz Merksamer Professor in the Department of Neurobiology and Behavior in the College of Arts and Sciences, told the Cornell Chronicle.

What the researchers wanted to understand was how the spiders could tell what was moving behind them when they have no ears.

It isn’t a question of peripheral vision. In a 2016 study, the same team blindfolded the spiders and sent them out to hunt, Science explained. This prevented the spiders from making their forward strikes, but they were still able to catch prey using the backwards strike. The researchers thought the spiders were “hearing” their prey with the sensors on the tips of their legs. All spiders have these sensors, but scientists had previously thought they were only able to detect vibrations through surfaces, not sounds in the air.

To test how well the ogre-faced spiders could actually hear, the researchers conducted a two-part experiment.

First, they inserted electrodes into removed spider legs and into the brains of intact spiders. They put the spiders and the legs into a vibration-proof booth and played sounds from two meters (approximately 6.5 feet) away. The spiders and the legs responded to sounds from 100 hertz to 10,000 hertz.

Next, they played the five sounds that had triggered the biggest response to 25 spiders in the wild and 51 spiders in the lab. More than half the spiders did the “backward strike” move when they heard sounds that have a lower frequency similar to insect wing beats. When the higher frequency sounds were played, the spiders did not move. This suggests the higher frequencies may mimic the sounds of predators like birds.

University of Cincinnati spider behavioral ecologist George Uetz told Science that the results were a “surprise” that indicated science has much to learn about spiders as a whole. Because all spiders have these receptors on their legs, it is possible that all spiders can hear. This theory was first put forward by Walcott 60 years ago, but was dismissed at the time, according to the Cornell Chronicle. But studies of other spiders have turned up further evidence since. A 2016 study found that a kind of jumping spider can pick up sonic vibrations in the air.

“We don’t know diddly about spiders,” Uetz told Science. “They are much more complex than people ever thought they were.”

Learning more provides scientists with an opportunity to study their sensory abilities in order to improve technology like bio-sensors, directional microphones and visual processing algorithms, Stafstrom told CNN.

Hoy agreed.

“The point is any understudied, underappreciated group has fascinating lives, even a yucky spider, and we can learn something from it,” he told CNN.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe