Data from a scientist measuring macroalgal communities in rocky shores in the Argentinean Patagonia would be added to the new system. Patricia Miloslavich / University of Delaware

Ocean scientists have been busy creating a global network to understand and measure changes in ocean life. The system will aggregate data from the oceans, climate and human activity to better inform sustainable marine management practices.

EcoWatch sat down with some of the scientists spearheading the collaboration to learn more.

“There is the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) and the Marine Biodiversity Observation Network (MBON). We’re trying to put them together,” explained Frank Muller-Karger, a professor at the University of South Florida studying phytoplankton, a member of the Biology & Ecosystems Panel (BioEco Panel) of GOOS and a co-founder of MBON.

GOOS recommends what kinds of essential measurements should be collected to address particular problems. Over the last few decades, physical variables (salinity, temperature, oxygen, etc.) have helped improved weather forecasts and understanding of how the ocean redistributes heat around the world, Muller-Karger said.

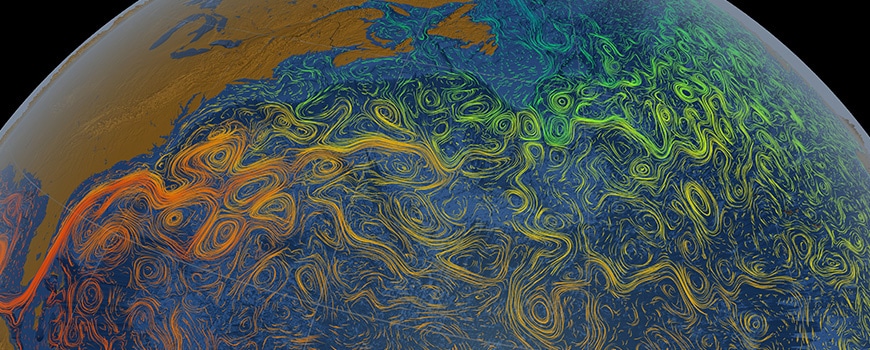

Climate models are predicting faster warming of the North Atlantic Ocean, which will shift the Gulf Stream. NASA

MBON has established biodiversity variables (genetics, number of species at a certain depth, ecosystem structure, etc.) to understand the structures of life in the oceans, explained Patricia Miloslavich, executive director of the Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research at the University of Delaware and member of both the BioEco Panel and MBON.

Now, scientists are trying to bridge the gap between the two observing networks by creating one “language” both systems can speak and in which all data can be collected and shared. A major goal is to be more efficient and effective in solving issues that affect people around the world by leveraging the oceans’ resources sustainably. The effort will be a key contribution to the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021 – 2030), an international effort under which top researchers have been collaborating to reverse ocean decline.

“Data have to be formatted and have to carry a measure of precision if you want any hope to understand how the world is changing,” Muller-Karger said. “It’s so difficult to make measurements in the sea, that if we don’t follow standards, we end up with things we cannot compare. It complicates things even further.”

Woody Turner, who works with NASA and remotely sensed data that will be incorporated into the new system, said the entire endeavor is about “coordination at a global scale to get a global view of the planet.” He noted that people have been looking at phenomena in the ocean for centuries and that the hard part has always been stitching these diverse observations together.

“That’s why the U.N. Decade is such a big deal. It’s an effort to bring together natural and social scientists from around the world to deliberately tie things together and create a standardized global observation system for it all,” he said.

The system will also link into a similar global climate observation system that has been in place for over 40 years, as well as account for human intervention. In this way, scientists hope to more fully understand how the two biggest stressors on the oceans — climate change and human activity — affect biodiversity and abundance of life in the oceans, Miloslavich said.

“This can be used by policymakers to better manage how we use the oceans,” she added.

For example, through the system, scientists could explain the fact that the oceans off the northeast U.S. are warming and document the how and why of a northward-migration of lobsters to forecast whether specific action may prevent the impending collapse of current fisheries and the resultant shift towards new species in the ecosystem.

Traditional climate data would show the effect of increased emissions of greenhouse gases, the GOOS might measure higher water temperatures, and the MBON might separately register the disappearing lobster populations, but the new system would hopefully be able to connect it all. Fisheries managers could then anticipate shortening or shifting a catch season accordingly, making the fishery more effective and profitable.

“We really need to be measuring life and the diversity of life, because that’s ultimately what we depend on,” Muller-Karger said. “We don’t eat bulk carbon; we eat fish and potatoes.”

Fundamentally, the scientists are trying to create a way to link physical and chemical measurements to the changes in biodiversity and life in the oceans.

“We need to be able to harness all that information so we can profit more from the info we’re collecting,” said Nic Bax, co-chair of the BioEco Panel. “That multi-disciplinarity is really needed now.”

Critically, the new integrated observing system also shows how human actions can increase biodiversity in a particular region, so that abundance and productivity can be used to improve human life in various ways, Bax explained.

For example, Turner and Maury Estes apply space-based satellite imagery of the Earth with sea-based measurements to improve aquaculture practices in Palau. This combats overfishing while sustaining the health of the people and the economy of the island nation. They are also applying such technologies to mangrove conservation and restoration efforts in Kenya, where carbon credits are purchased to maintain mangroves as essential fish spawning grounds, increasing biological resilience while reducing human poverty.

“As we understand more, how we talk about sustainably developing the environment won’t be just about how to not lose diversity, but about how to bring it back,” Bax said. “A lot of things just require someone to invest in them, and financial markets need to be informed about what’s going on in the larger system. This is a way to generate profit while improving the lives of people.”

Turner added, “It’s not only about saving life on the planet, it’s about saving ourselves. It’s a global problem, so we have to address it top-down, globally.”

- Could the Climate Crisis Spell the End for Maine Lobster? - EcoWatch

- 5 Reasons Why Biodiversity Matters - EcoWatch

- World Leaders, Media Ignore Biodiversity Report Detailing Mass ...

- The Top 10 Ocean Biodiversity Hotspots to Protect - EcoWatch

- Scientists to Explore Mysterious Blue Hole off Florida - EcoWatch

- 14 Countries Commit to Ocean Sustainability Initiative

- Scientists Launch ‘Four Steps for Earth’ to Protect Biodiversity - EcoWatch

- Biodiversity: Everything You Need to Know

- Oceanic Global Launches 'Blue Standard' to Create Sustainable Industries for the Ocean - EcoWatch

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe