David Mark / Pixabay

By Douglas McCauley

This article is part of The Davos Agenda.

The year 2050 has been predicted by some to be a bleak year for the ocean. Experts say that by 2050 there may be more plastic than fish in the sea, or perhaps only plastic left. Others say 90% of our coral reefs may be dead, waves of mass marine extinction may be unleashed, and our seas may be left overheated, acidified and lacking oxygen.

It is easy to forget that 2050 is not that far off. Kids we see building sandcastles on the beach today might be gaining traction in their jobs and perhaps starting their own families. The possibility that our children may inherit from us such a broken and diminished ocean is hard to accept.

Such a future, however, is not yet written in stone. A healthier, more whole, and maybe even more profitable future ocean may still be within reach – at least for a little while.

Here are 10 steps that could take us towards a more desirable ocean future:

1. Freeze the warming. Stopping climate change is the hardest but most important step we can take for ocean health. It is good news to have the US back in the Paris Agreement. However, we now need ambitious national commitments to achieve carbon neutrality from all signatories of the Agreement. Recent actions by China, the EU, Japan and the UK are also positive.

2. Walk the talk. We need to make these carbon neutrality commitments real. This will require massive new investment in renewable energy sources, including some more experimental solutions (such as fusion), plus potentially looking with open minds into making older low-carbon energy solutions safer and more viable (such as traditional nuclear). We need to fast-track the development of sustainable next-generation batteries to store this energy intelligently across our grids. This includes major needs for marine energy infrastructure. A future, for example, with electrified ports and low-emission ships would help eliminate the epidemic of deafening ocean noise, address environmental injustices associated with pollution in ports, make oil spills a thing of the past, and significantly reduce global emissions.

A NASA model showing CO2 (the yellow/red swirls) moving across the globe.

3. Blue revolution. The “green revolution” – a massive ramping up of food production on land in the 1950s – has belatedly reached the sea. Ocean farming, or aquaculture, has increased by more than 1,000% in the ocean recently. The green revolution was sloppily executed, and the first baby steps of the blue revolution have included similar stumbles: chemical pollution, genetic pollution and habitat destruction. But the blue revolution can still clean up its act. Farming in the right places, with the right species, and the right practices could make aquaculture a win for human and environmental health. Ocean food research (into plant-based and cell-based seafood, for example) could also help us meet growing demand for seafood sustainably.

4. 30 x 30. Parks protect some of our most important chunks of nature on land – our Yellowstones and Serengetis. We are vastly behind setting up parks in the sea. We need to follow through on calls to protect 30% of our ocean by 2030. This must be as much about quality as quantity. We need to use intelligent planning algorithms and the intelligence of local and indigenous people to select the very best 30% of the sea to protect. Then the hard work begins. We must develop and deploy new technology to monitor and protect the living assets we put in these ocean savings accounts.

5. The other 70%. An ocean industrial revolution is beginning. Human industry is growing at exponential rates in the sea. Even if we succeed in protecting 30% of the ocean, we must still intelligently zone and manage this accelerated anthropogenic growth in the majority of our unprotected ocean. We largely missed that boat on land. Proactive steps to sustainably onboard an ocean industrial revolution include responsibly managing wild capture fisheries (and making more money in the process), carefully zoning what marine industries go where, eliminating harmful fisheries subsidies, and coming to grips with the fact that some new marine industries, like ocean mining, are simply too dangerous to be allowed into the ocean.

6. Big cracks in the sea. Most of the ocean belongs to us all. This includes the two-thirds of the ocean in the high seas that lies beyond all nations’ ocean borders and the marine regions surrounding Antarctica. Protection of biodiversity and equitable sharing of resources has slipped through antiquated governance gaps in these international ocean spaces. But a proposed new UN Treaty for high seas biodiversity – and negotiations to sustainably manage and protect Antarctic waters could help.

7. End plastic pollution. Plastic pollution is the ocean’s new cancer. We need to ban unnecessary plastics and tax other single use plastics, finally making them valuable materials we want to recover and helping to pay for the full cost of their environmental impacts. We need research and tech to prevent plastics from leaking into the sea, to overhaul our recycling systems, and to design economically viable alternatives to plastics. This progress may be accelerated by a proposed international ‘Paris Agreement’ for plastic pollution.

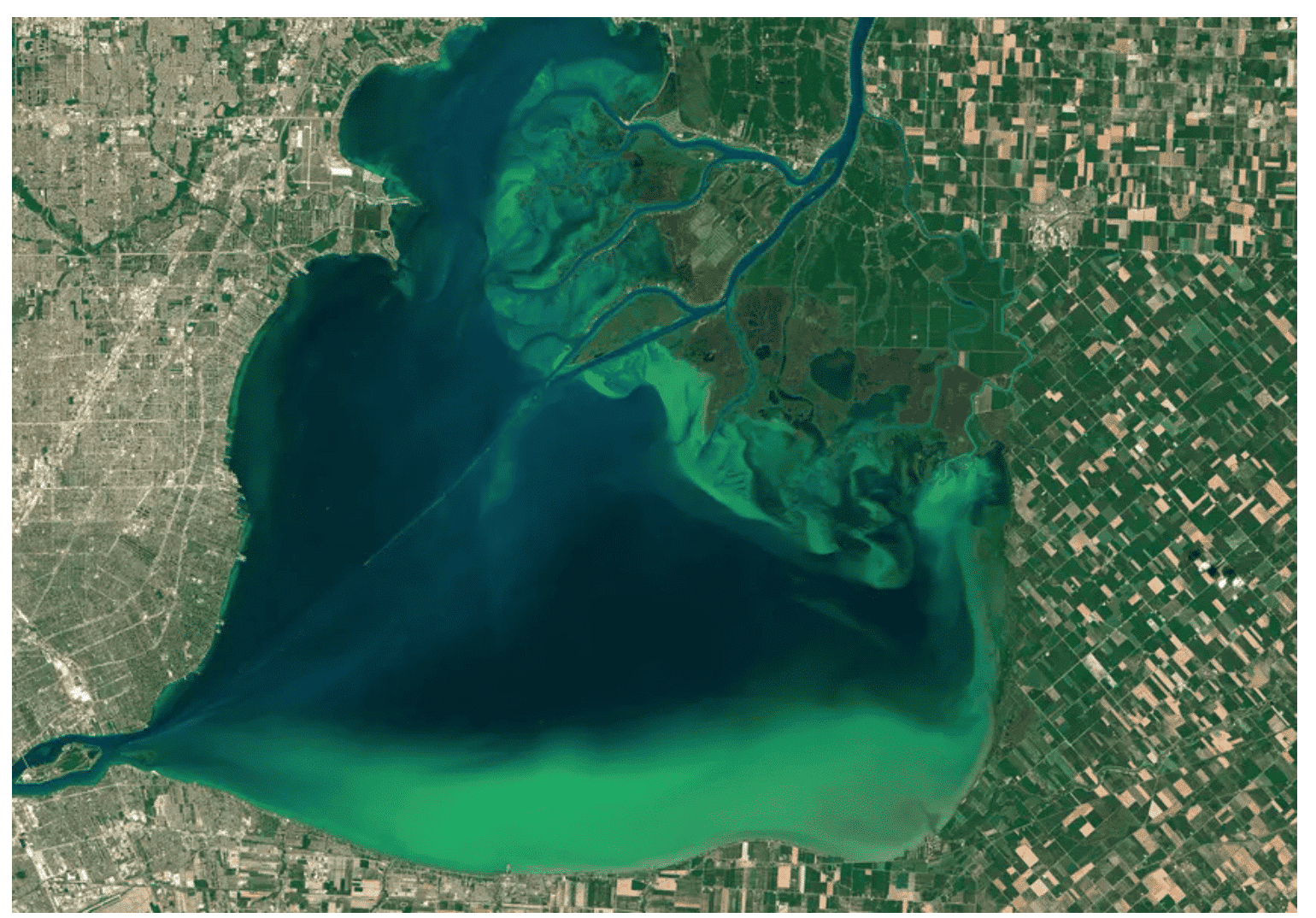

8. Land. We can help the ocean by first setting a few things right on land. We must massively increase our ambition to save our forests, thus locking up a huge chunk of carbon dioxide. We need to stop wastefully spilling megatons of costly fertilizers into rivers that are creating hundreds of marine dead zones. Precision agriculture that optimizes fertilizer use, coupled with other farming reform practices can help.

An algal bloom seen in Lake St. Clair, between Michigan and Ontario, in 2015. NASA

9. Wired ocean. We need more ocean data. This includes new tech to detect illegal fishing and connect sustainable fishers to consumers. We need tech to help endangered marine wildlife co-exist with ocean industry and fleets of environmental sensors above and below the water to better study our rapidly changing ocean.

10. Ocean equity. To build a healthy ocean, we must ensure all people have a fair stake in its success and that they are no longer unevenly harmed by ocean health risks. The fate of the ocean will affect people in all communities. Thus, we need people from all communities in ocean science, management, and policy.

Fulfilling the apocalyptic predictions for a 2050 ocean will be all too easy. Altering that ocean future may be one of the hardest things we’ve ever collectively achieved. But the consequences of inaction will be even harder to shoulder – for us and our ocean.

Reposted with permission from World Economic Forum.

- The Top 10 Ocean Biodiversity Hotspots to Protect - EcoWatch

- 15 Top Conservation Issues of 2021 Include Big Threats, Potential ...

- What if We Treated Our Oceans as if They Matter? - EcoWatch

- House Democrats Introduce Ocean-Based Climate Solutions Act ...

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe