By Emilie Karrick Surrusco

It’s been nearly four months since Hurricane Florence battered the North Carolina coast, dumping 9 trillion gallons of water on the state in the span of four days. In Duplin County, home to the nation’s largest concentration of industrial hog operations, the storm’s deluge laid bare problems that persist in good weather and in bad.

Hurricanes are becoming more commonplace in the southeastern U.S.—since 1999, at least four hurricanes and tropical storms have brought enough precipitation to North Carolina to qualify as “100-year” storms. There is barely time to rebuild and recover before the next storm hits.

“A lot of people are still displaced, a lot of people still aren’t sure what tomorrow is going to hold,” said Devon Hall, co-founder of the Rural Empowerment Association for Community Help (REACH) in Duplin County. “What is normalcy? When we look at the frequency of these storms now, it just keeps happening over and over again.”

The flooding caused by these hurricanes exacerbates problems caused by the failure of industrial hog operations, also known as concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), to adequately store or maintain the massive amounts of waste produced by the 2.2 million hogs in Duplin County alone.

Each year, CAFOs in Duplin County produce twice as much urine and feces as the entire New York City metro area. Much of that waste is stored in thousands of hog “lagoons”—open-air pits clustered in the area hardest hit by Hurricane Florence.

When it rains too much, these poop-filled pits—which carry E. coli, salmonella, cryptosporidium, and other harmful bacteria – overflow into surrounding rivers and streams, or sustain catastrophic structural damage.

As a result of Hurricane Florence, 49 lagoons were reported to be damaged structurally, actively discharging material, or inundated with surface water, while another 60 nearly flooded, according to the state’s Department of Environmental Quality.

When all this pig poop is unleashed on the surrounding environment, local residents, who are disproportionately African American, Latino or Native American, live with the consequences—which begin with contaminated drinking water.

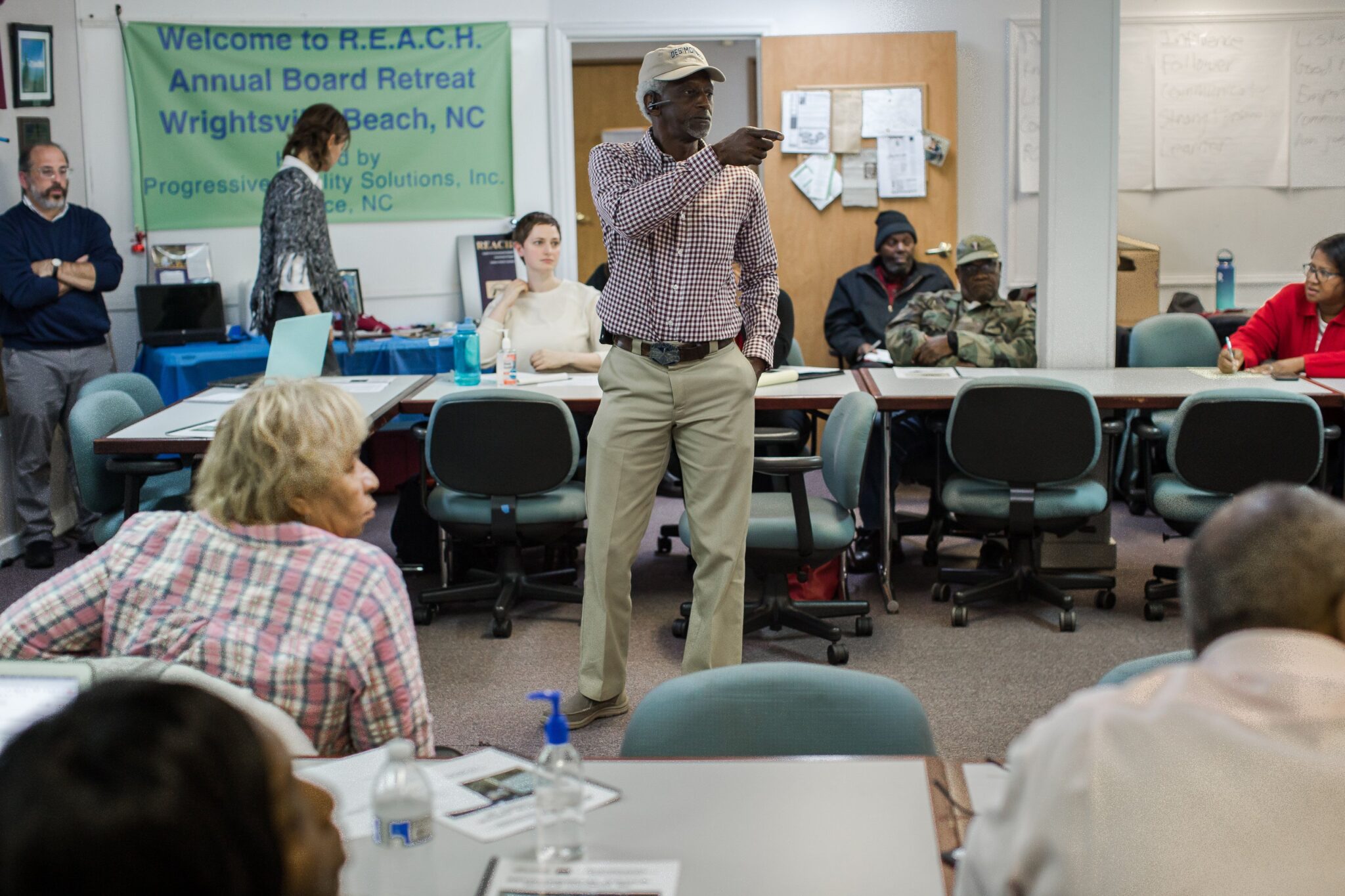

Devon Hall, executive director of REACH, is fighting against air and water pollution from the CAFOs that surround his community.

Justin Cook / Earthjustice

“People don’t have drinking water,” said Hall, who with REACH has been passing out bottled water since the hurricane. The organization has repeatedly run out because the demand is so high.

A recent article in the News & Observer notes that several hundred samples of private well water analyzed by the state Laboratory of Public Health showed a marked increase in E. coli after Hurricane Florence. In fact, 14.9 percent of the wells tested positive for E. coli and fecal coliform bacteria—as compared to 2 percent that tested positive in the months before the hurricane hit. Out of all 50 states, North Carolina ranks second in number of people who rely on private wells for drinking water.

None of this is new for local residents. Hall and others have been fighting for decades against air and water pollution from the CAFOs that surround them, as well as a pervading stench that forces people inside their homes.

The resulting health problems are well documented. A new Duke University study shows that people living in communities with the highest density of hog operations experienced 30 percent more deaths among patients with kidney disease, 50 percent more deaths among patients with anemia, and 130 percent more deaths among patients with sepsis, as compared to people in communities without big hog operations.

Despite the obvious health impacts, the EPA has exempted CAFOs from notifying authorities and communities when they release dangerous quantities of toxic gases. On behalf of Waterkeeper Alliance and Sierra Club, and several local environmental groups including REACH, Earthjustice filed a lawsuit on Sept. 14, 2018 to force the agency to disclose public records that could shed light on this decision. Earthjustice filed another lawsuit on Sept. 28, 2018 that asks the court to reverse the exemption and force CAFOs to report toxic emissions before they sicken surrounding communities.

“Lack of transparency is a huge problem,” said Alexis Andiman, an attorney with Earthjustice. “People deserve to know what they’re breathing and how it could affect their health.”

There are better ways for North Carolina’s CAFOs to store and manage pig waste—and prepare for increasingly severe storms. As Waterkeeper Alliance staff attorney Will Hendrick contends, they could learn from the past.

“It’s sadly predictable,” he said. “We’ve seen it all before, and it’s something that we should have taken steps to avoid. It’s not going to get better until we make changes. The need for action increases as climate change increases the vulnerability of the coastal area to these storms.”

There are two changes that the state’s hog industry—dominated by Smithfield Foods, a corporation that owns roughly three-quarters of the hogs produced in North Carolina—could make to reduce pollution and get ready for future storms.

A CAFO in Warsaw, North Carolina.

Justin Cook / Earthjustice

The first involves moving industrial animal operations out of the 100-year flood plain. After Hurricane Floyd in 1999, the state created a buyout program for industrial hog operations in flood-prone areas. The program was inundated with applications, and in the end, only had enough funding to buy out 45 industrial animal operations. Today, there are 123 industrial hog operations within 500 feet of the 100-year flood plain, along with 40 industrial poultry operations, according to Waterkeeper Alliance.

The state recently announced $5 million in funding for another round of buyouts, according to NC Policy Watch. However, some local residents are concerned that the program will steer taxpayer dollars toward industry-owned CAFOs, as opposed to those operated by independent contractors.

The second needed change involves the way that CAFOs store and manage waste. Currently, many industrial hog operations lower the level of waste in their lagoons by spraying it on surrounding fields.

State permits prohibit spraying more than four hours after a hurricane warning, as well as when fields are flooded or saturated with water, because the waste runs off fields into rivers when the rains come and causes contamination and pollution with dire impacts for both humans and wildlife. However, many CAFOs operators disregard this rule.

“Many CAFO operators are between a rock and a hard place,” Hall explains. “They are also victims of the industry’s greed.”

The North Carolina Pork Council touted this practice in preparation for Hurricane Florence, saying they lowered “the levels of the lagoons to accommodate more rainwater, using the manure as fertilizer in nearby fields,” even though the waste can’t act as a fertilizer if its washed off the fields by rain.

Industrial pig operations operate under a waste management permit that is revised and renewed every five years. This permit has remained unchanged for almost two decades. This year could be different.

Last spring, Earthjustice—working in partnership with Yale Law School’s Environmental Justice Clinic and the North Carolina-based Chambers Center for Civil Rights—settled a civil rights complaint filed in 2014 on behalf of REACH, the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network (NCEJN), and Waterkeeper Alliance. The complaint alleged that DEQ allowed industrial swine facilities to operate with “grossly inadequate and outdated systems of controlling animal waste” resulting in an “unjustified disproportionate impact on the basis of race and national origin against African Americans, Latinos and Native Americans.”

As part of the settlement, DEQ agreed to allow community members to play a greater in the development of its swine waste management permit. DEQ also agreed to update its storm standards—requiring industrial hog operations to better prepare for storms. But those new standards have yet to take effect.

Last month, Earthjustice and our partners submitted “stakeholder” comments on DEQ’s latest draft permit, on behalf of REACH, NCEJN and Waterkeeper. We applauded DEQ’s decision to propose stronger storm standards, in line with our civil rights settlement, and urged the agency to take additional steps to protect communities and the environment. A revised draft permit will be available for public review later this year.

Devon Hall speaks at a REACH meeting.

Justin Cook / Earthjustice

Industrial pig operations, and Smithfield Foods in particular, could take advantage of promising technologies, such as removing the waste from the animals with dry scraping rather than water. This practice would reduce the amount of waste that needs to be stored in a lagoon or spread on a field, and slow the generation of toxic air pollution. Smithfield claims that “high-tech” solutions are too expensive. Instead, the corporation recently announced plans to invest in cesspool covers and digesters that will convert swine waste to energy.

Unfortunately, as Hendrick notes, covers and digesters will do nothing to prevent groundwater contamination, eliminate the noxious stench, or stop the damage caused by spraying nearby fields. What they will do is generate more revenue for Smithfield.

Earthjustice attorney Alexis Andiman, front, attends a REACH meeting.

Justin Cook / Earthjustice

“Smithfield can afford multi-million dollar bonuses for their executives, they can afford multi-billion dollars in profits, they can afford to externalize pollution, but they can’t afford ways to better manage their waste,” said Hendrick.

In the wake of Hurricane Florence, Earthjustice will continue to work alongside Hall and other local partners to ensure that the voices of local residents are heard—even when there isn’t a cloud in the sky.

“These facilities threaten people every day,” said Andiman. “The lagoon-and-sprayfield system is flawed and dangerous at the best of times, and it’s become a ticking time bomb with climate change. We need North Carolina to commit to stricter oversight of these facilities, so that people are safer now—and when the next hurricane hits.”

Emilie has spent the past two decades as a journalist, speechwriter and communications strategist in Washington, DC. At Earthjustice, she shares the stories of the people and issues at the heart of our clean energy litigation and policy work.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe