A Few Heavy Storms Cause a Big Chunk of Nitrogen Pollution From Midwest Farms

A flooded corn field along the Yazoo River during the Mississippi River near Redwood, Mississippi in May of 2011.

T. C. Knight / Getty Images

By Chaoqun Lu

Some effects of extreme weather are visible – like half a million acres of flattened corn in Iowa left behind after a derecho that hit the Midwestern United States on Aug. 10.

Other effects are harder to measure, but can be just as harmful. One example is agricultural nitrogen runoff from farmlands in the Mississippi River Basin. It mainly comes from fertilizer that farmers apply to millions of acres of crops.

Plants can’t use all of the nitrogen in fertilizer because fertilizers are usually applied in excess. This excess can wash off farm fields into local rivers and lakes, degrading water quality and stimulating algae blooms. Traveling down the Mississippi River, it contributes to the yearly formation of a dead zone in the northern Gulf of Mexico, covering several thousand square miles; oxygen levels there are so low that fish and shellfish cannot survive.

The Mississippi River Basin covers over 1.245 million square miles across 32 U.S. states and two Canadian provinces. Shannon1 / Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 4.0

Excess nitrogen in drinking water also threatens public health. Ingesting high levels of nitrate, a nitrogen compound, can reduce red blood cells’ ability to transport oxygen, a condition that is especially dangerous for infants.

My work as a quantitative ecologist examines how ecosystems respond to external factors such as adding nitrogen. In a recently published study, I worked with colleagues to quantify nitrogen runoff from land into rivers and streams. We found that infrequent but heavy rainfall events account for one-third of annual total runoff and nitrogen leaching from soils across the Mississippi Basin. This tells us that managing nitrogen is likely to be more challenging if climate change continues to make heavy rains more frequent.

Too Much of a Good Thing

Plants can’t grow without nitrogen, but using too much or applying it improperly can cause problems. In the U.S. Midwest, one of the most intensively farmed areas in the world, farmers have added large amounts of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer to the land to boost crop yields.

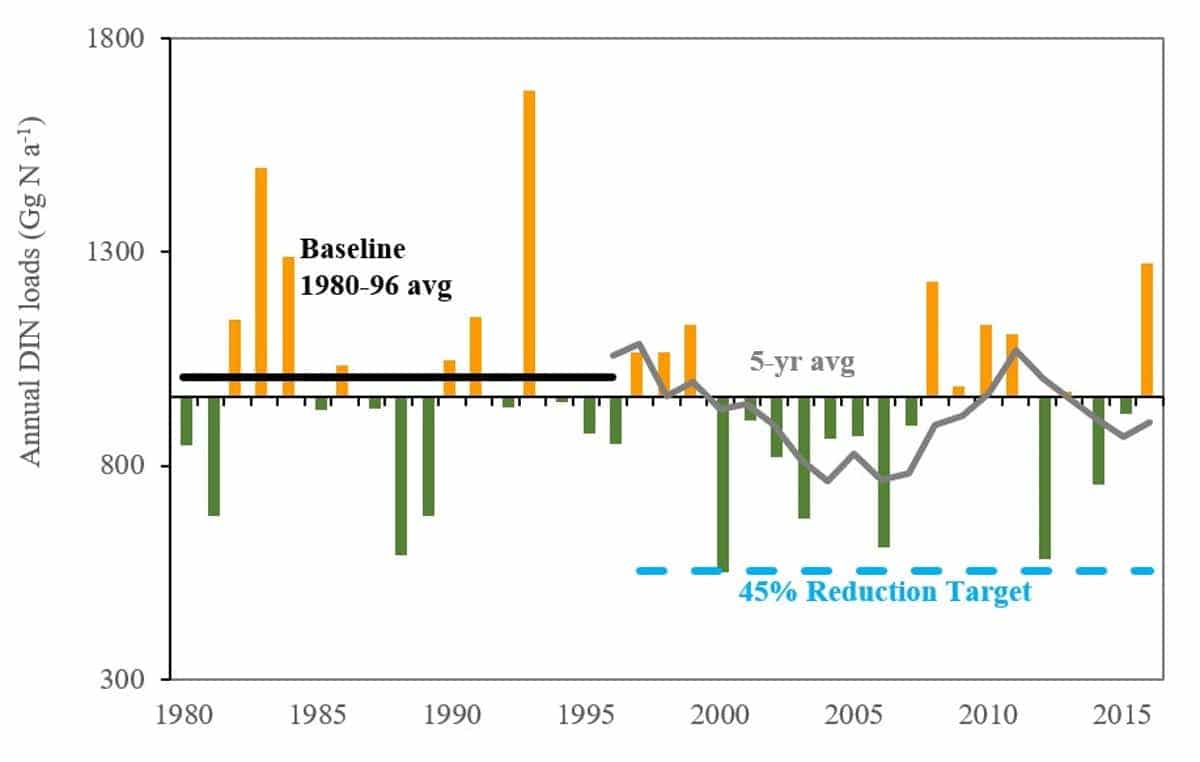

Long-term monitoring data from river gauges shows large year-to-year variations in the quantity of nitrogen that flows down from the Mississippi River Basin into the Gulf of Mexico. Yearly changes in farmers’ fertilizer use are not large enough to explain these fluctuations.

Studies show that annual total precipitation is a significant factor in these changes. But we know less about the role of daily rainfall – particularly heavy rains – in mobilizing and transporting nitrogen.

Stream gauge measurements show that the amount of dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) moving from Mississippi River Basin states to the Gulf of Mexico fluctuates dramatically from year to year. Heavy rainfalls can produce higher nitrogen levels. Modified from Lu et al., 2020, CC BY-ND

Heavy Rains Have an Outsized Impact

My collaborators and I wanted to assess the impacts of extreme rainfall events in the Midwest. In this region, many cropped fields are laced with buried networks of drainage channels, known locally as tile drainage. These pipelines are designed to move excess moisture out of fields. But they can also channel large surges of water and nutrients into rivers and streams after heavy rainfalls.

It is challenging to determine how individual rainfall events affect nitrogen leaching and movement within a drainage basin. Rain happens here and there, so it’s hard to distinguish a single storm’s impact from river gauge monitoring data. Rainfall events also vary a lot by season and intensity.

Our study used a well-tested model to quantify how much nitrogen is washed out by each rainfall event, as well as total nitrogen delivered to the Gulf of Mexico. We looked closely at heavy rainfall events, which we defined as the top 10% of historical daily precipitation amounts for any location in a given month.

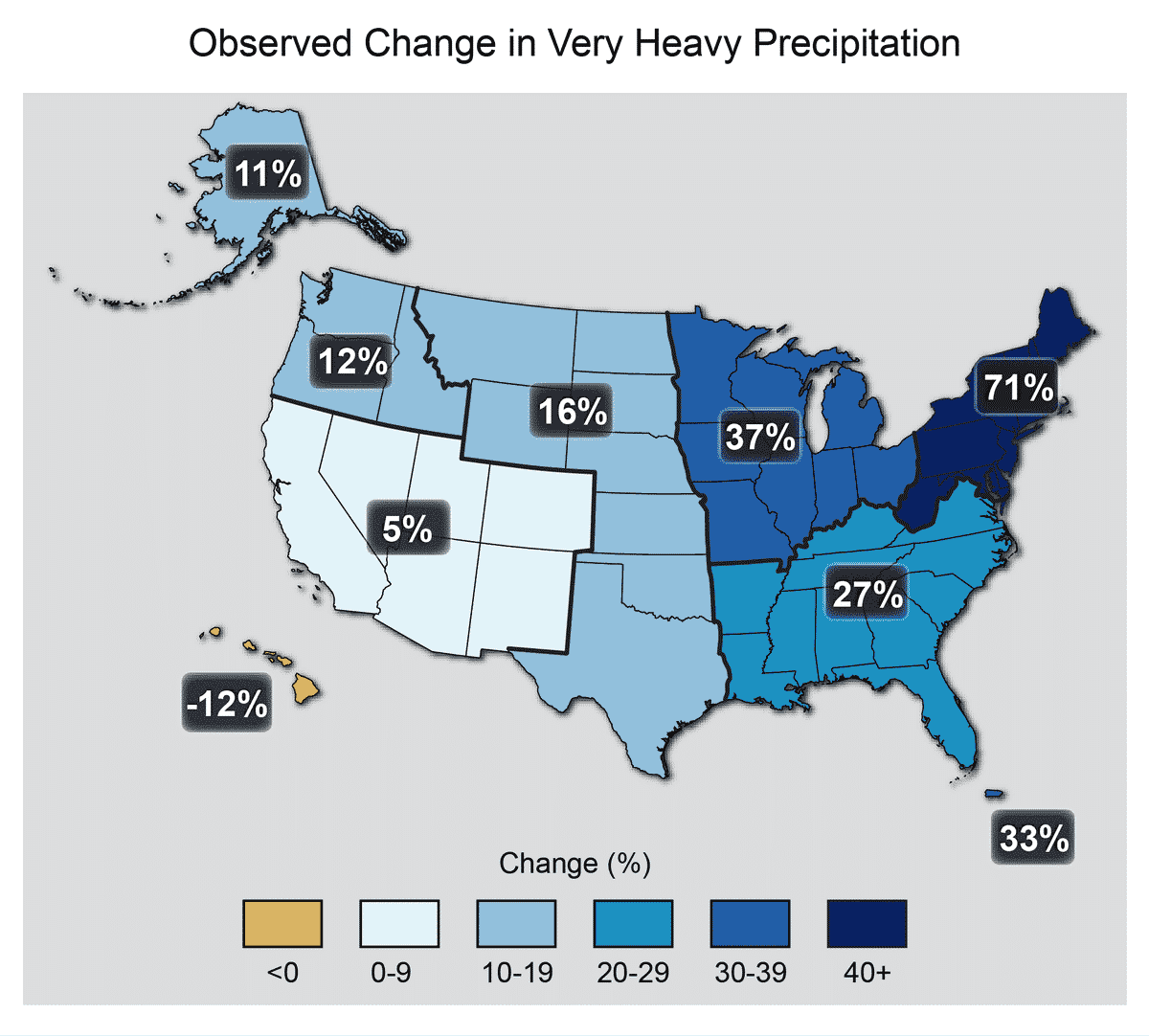

Climate records show that over the past 20 years, a growing share of annual precipitation has come in heavy rainfall events across two-thirds of the Mississippi River Basin’s land area. The region that receives a total of more than 15.7 inches (400 millimeters) of heavy rain per year has expanded from areas in Louisiana and Arkansas northward to Corn Belt states like Illinois and Indiana, where nitrogen fertilizer is heavily used.

Percentage increases in the amount of precipitation falling in very heavy events (defined as the heaviest 1% of all daily events) from 1958 to 2012. Globalchange.gov

We found that one-third of annual total runoff and nitrogen leaching loss come from heavy rainfall events, which happen on only about nine days per year on average across the basin. Nearly half to three-quarters of heavy rainfall in the basin occurs in spring and summer, with a monthly peak in May.

This timing coincides with the planting and seed germinating stages of corn, when the plants are using minimal amounts of nitrogen. We wondered whether changing when and how farmers apply fertilizer could reduce nitrogen runoff.

When to Fertilize

When during the year to apply fertilizer is a long-standing question in both precision agriculture and environmental science. Midwest farmers apply over 90% of nitrogen fertilizer before crops germinate in springtime and after harvesting. This means that a fair amount of available nitrogen accumulates in the soil before crops start taking it up. When heavy rainfalls occur, it is likely to be washed out.

Nitrogen fertilizer application restrictions on crop ground went into effect in certain areas of Minnesota on Sept. 1.https://t.co/3scnh3wJlV

— DTN/Progressive Farmer (@dtnpf) October 19, 2020

We set up modeling experiments to test whether postponing fertilizer application could make the water running off of farmlands cleaner. In our alternative fertilizer management scenario, we assumed fertilizer was applied only twice, after crops developed. We expected this would reduce the amount of unused nitrogen accumulating in soils.

Our results predicted that this modification could reduce nitrogen loading to the Gulf of Mexico by up to 16%. This would be a significant step toward goals set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which is working with states to reduce nutrient loads entering the Gulf of Mexico by 20% by 2025 and 45% by 2035.

However, even under the postponed fertilizer application scenario, we still found the frequent heavy rains in the recent decade could enhance nitrogen loss during summer and early fall. Scientists predict that if climate change continues at its current rate, it will cause more extreme rainfall events in the Midwest, which, we think, would reduce environmental benefits from alternative nitrogen management practices.

Reducing the amount of nitrogen that escapes from land into water bodies while maintaining food production is a significant challenge. Our study complements the well-known 4R concept for managing nutrients: Using the right fertilizer product, at the right rate, at the right time, and in the right place. To get that timing right, our research shows that along with crop nitrogen demand, farmers should also consider the occurrence of heavy rainfall.

Chaoqun Lu is an assistant professor of Ecology, Evolution and Organismal Biology at Iowa State University.

Disclosure statement: Chaoqun Lu receives funding from the National Science Foundation, Iowa State University, and the Iowa Nutrient Research Center.

Reposted with permission from The Conversation.

- How Your Diet Contributes to Nutrient Pollution and Dead Zones in ...

- A Brief Guide to the Impacts of Climate Change on Food Production ...

- Scientists Find New Way to Reduce Marine ‘Dead Zones’

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe