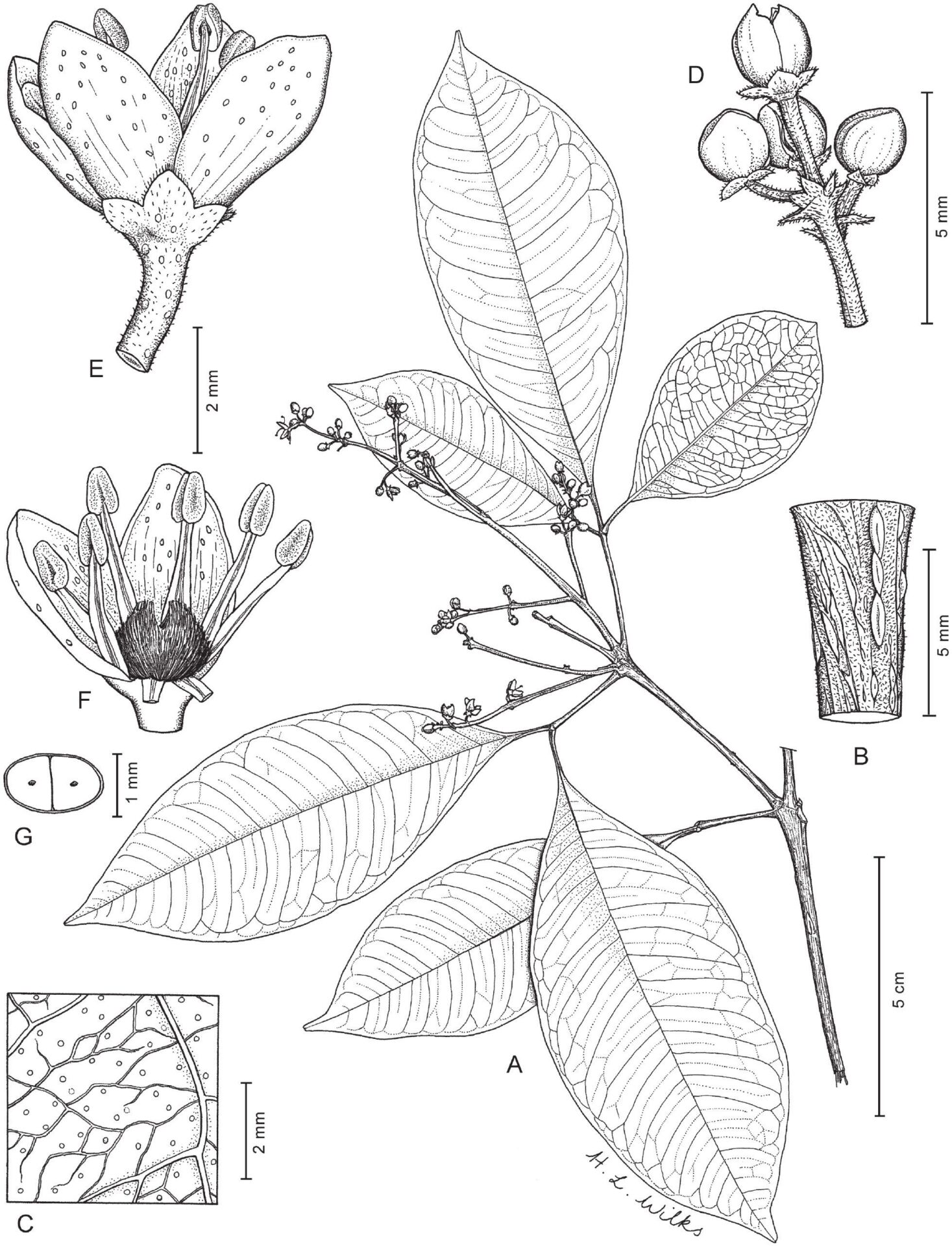

A drawing of the new species. By Hazel Wilks / Willdenowia / CC BY 4.0 license

By John R. Platt

Sometimes you don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone.

In 1951 a member of the Nigerian Forestry Service collected specimens of a rare tree in the highlands of northwestern Cameroon. It was soon identified as a member of the Vepris genus, a group of 80 or so large tree species that range throughout the African continent and the islands of Madagascar and Zanzibar. Unfortunately the specimens were incomplete, and full identification of the species was not, at the time, achieved.

Now, nearly 70 years later, the species has been named—just in time to etch that name on its tombstone. A paper published Aug. 24 in the journal Willdenowia identifies the species as Vepris bali and declares its likely extinction due to agricultural development in the tree’s only known habitat, the Bali Ngemba Forest Reserve. Researchers examined the original specimens and used molecular phylogenetic studies to identify the new species.

A drawing of the new species.Hazel Wilks / Willdenowia / CC BY 4.0 License

The authors—from Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew and the University of Yaoundé I—note that previous attempts to locate this species and complete the 1951 specimen, including “repeated targeted efforts” between the years 2000 and 2004 and at least six other studies, failed to turn up any sign that the tree still exists.

That doesn’t mean they’ve completely given up hope, though. In 2011 the same authors rediscovered another tree species, Ternstroemia cameroonensis, which had previously been declared extinct.

Can the same thing happen with Vepris bali? As the authors write in the paper, “It is hoped that naming this species will relaunch efforts to rediscover and protect this species from extinction.” For now they’re officially declaring it as critically endangered, although they acknowledge that “the reality is that V. bali may already be extinct.”

Even if it is gone, the authors use their paper on Vepris bali as an opportunity to call for action on other plants, especially those, like this tree, that exist in small ranges and habitats. In particular they expect several other Vepris species—which are currently being studied for the antimicrobial and antimalarial applications of their essential oils—to be identified and named in Cameroon yet, hopefully before they also disappear.

Worldwide, thousands if not millions of plant species face similar risks. According to the International Plant Names Index, about 2,000 new plant species are named ever year, but relatively few—about 5 percent of all known species—have ever been formally assessed for their extinction risk. As the authors write in their paper, “this makes it a priority to discovery, document and protect such species before they become globally extinct.”

Reposted with permission from our media associate The Revelator.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe