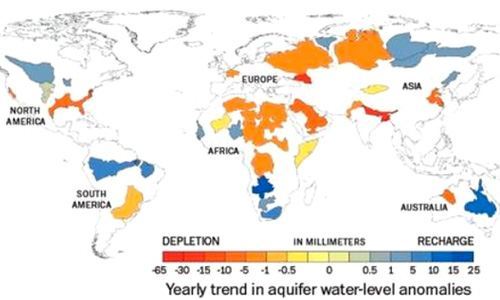

NASA: More Than One-Third of Earth’s Largest Aquifers Are Being Rapidly Depleted

Think the water situation is bad in California? Freshwater is depleting at alarming and unsustainable rates in major underground aquifers around the globe, according to NASA satellite images.

~1/3rd of Earth’s largest groundwater basins are being rapidly depleted says new study: http://t.co/sEMnRmFSe7 pic.twitter.com/YBo4f30FFL

— NASA (@NASA) June 17, 2015

Researchers from the University of California, Irvine (UCI) used data from NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellites and discovered that one third of the Earth’s largest groundwater basins are rapidly depleting due to human consumption, and will only get worse with the changing climate. The research was published in two complimentary studies in the Water Resources Research journal.

These aquifers are a crucial source of fresh water for 35 percent of the human population. That’s more than 2 billion people.

What’s most alarming, according to one of the studies, is how there’s insufficient accurate information on how much water remains in the basins, which means “significant segments of Earth’s population are consuming groundwater quickly without knowing when it might run out,” the researchers concluded in a news release.

“Available physical and chemical measurements are simply insufficient,” UCI professor and principal investigator Jay Famiglietti, who is also the senior water scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California said in the release. “Given how quickly we are consuming the world’s groundwater reserves, we need a coordinated global effort to determine how much is left.”

The world’s driest areas contain the most overburdened aquifers. The Arabian Aquifer System, the Indus Basin aquifer of northwestern India and Pakistan, and the Murzuk-Djado Basin in northern Africa are the top three most overstressed aquifers in the world.

In the U.S., California’s Central Valley Aquifer—which is being sucked up for agricultural uses—is the most troubled aquifer in the country. While it is fairing slightly better than the aforementioned aquifers, the researchers still consider it “highly stressed.” The water-pinched Golden State is wringing its groundwater more than ever due to the historic and ongoing drought.

“As we’re seeing in California right now, we rely much more heavily on groundwater during drought,” said Famiglietti. “When examining the sustainability of a region’s water resources, we absolutely must account for that dependence.”

This shocking map shows that the world is running out of water http://t.co/SiWblXO6mx pic.twitter.com/H6lCJKAS5t

— The Independent (@Independent) June 17, 2015

Washington Post reporter Todd C. Frankel noted from one of the studies that 21 of the 37 largest aquifers in the world, “have passed their sustainability tipping points,” meaning that more water is being used than replenished.

“Aquifers can take thousands of years to fill up and only slowly recharge with water from snowmelt and rains,” Frankel wrote. “Now, as drilling for water has taken off across the globe, the hidden water reservoirs are being stressed.”

Here’s the takeaway: The world’s water woes will only get worse as dependence on underground water increases. Climate change and population growth will only exacerbate the problem, researchers pointed out.

“What happens when a highly stressed aquifer is located in a region with socioeconomic or political tensions that can’t supplement declining water supplies fast enough?” said Alexandra Richey, the lead author on both studies, in the news release. “We’re trying to raise red flags now to pinpoint where active management today could protect future lives and livelihoods.”

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE

Drought-Stricken California Orders Largest Recorded Water Cuts for Farmers

Lake Mead About to Hit a Critical New Low as 15-Year Drought Continues in Southwest

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe