Rising Temperatures Will Help Mosquitos Infect a Billion More People

Pexels

By Marlene Cimons

Mosquitoes are unrelenting killers. In fact, they are among the most lethal animals in the world. When they carry dangerous viruses or other organisms, a bite can be unforgiving. They cause millions of deaths every year from such infectious diseases as malaria, dengue, Zika, chikungunya, yellow fever and at least a dozen more.

But here’s the really bad news: climate change is expected to make them even deadlier. As the planet heats up, these insects will survive winter and proliferate, causing an estimated billion or more new infections by the end of the century, according to new research.

“Plain and simple, climate change is going to kill a lot of people,” said biologist Colin J. Carlson, a postdoctoral fellow in Georgetown University’s biology department, and co-author of the study, published in the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. “Mosquito-borne diseases are going to be a big way that happens, especially as they spread from the tropics to temperate countries.”

The study predicted an amenable climate could prompt some of these new cases within regions not previously regarded as vulnerable, including the U.S. These viruses can result in volatile outbreaks when conditions are right, as was the case with Zika. “We’ve known about Zika since 1947, and we watched it slowly spread around the world until 2015, when it arrived in Brazil and suddenly we had an explosive epidemic on our hands,” Carlson said.

“Chikungunya has done something not too different from that,” he added. “These viruses proliferate quickly in populations that don’t have any immunity — and we’re very scared about that. If you only have one month that’s warm enough for outbreaks, the question is: ‘how much damage you can do…?’ For viruses like these, it’s a lot.”

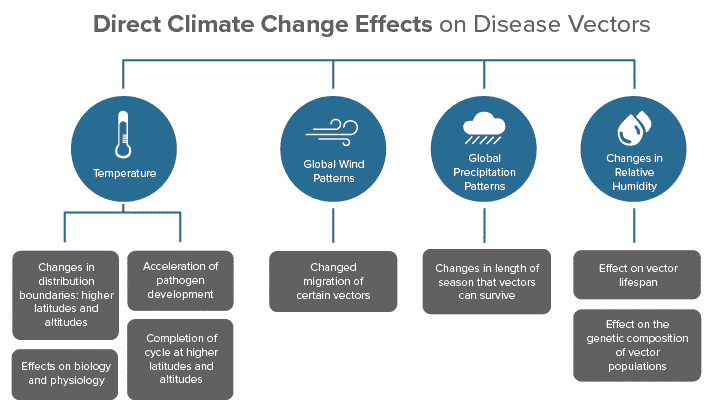

The study underscores the growing evidence that climate change is having — and will continue to have — a deleterious impact on global health, not only from the direct effects of extreme weather events like heat waves and flooding, but also because mosquitoes thrive in warm temperatures and carbon dioxide, encouraging them to flourish and spread disease. Rising temperatures also are causing many to migrate to new locations.

“This is a very important forward-looking report,” said Robert T. Schooley, an infectious diseases expert at the University of California, San Diego, and editor of the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, who was not involved in this study. “Understanding in as much detail as possible the risks we face as we move toward a warmer planet is essential. Mosquitoes are able to spread blood-borne pathogens faster than epidemiologists can track an epidemic. There are many one-way doors through which we will go as the planet warms. The spread of mosquitoes and other vectors that can transmit multiple pathogens is an important one that those who don’t think climate change is a serious problem should ponder.”

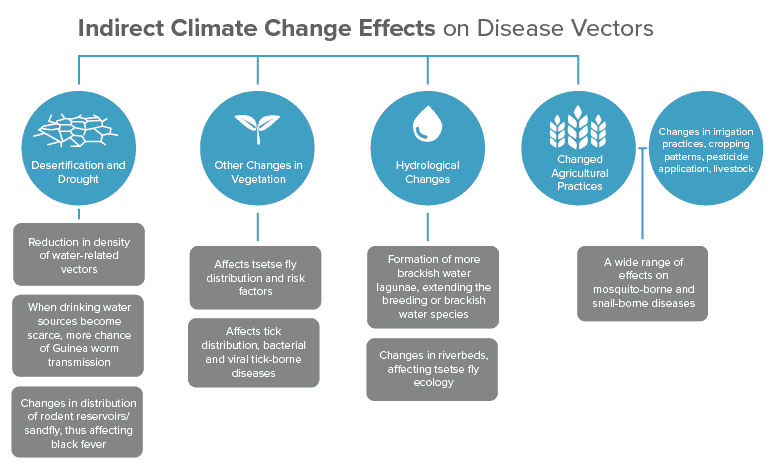

The research team, also led by Sadie J. Ryan, of the University of Florida’s emerging pathogens institute and associate professor of medical geography, looked what would happen to the two most common disease-carrying mosquitoes, Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, as temperatures increase during the coming decades. It found that global warming will expose almost all of the world’s population to mosquitoes at some point in the next 50 years. Also, there likely will be year-round transmissions in the tropics and seasonal risks almost everywhere else, along with a greater intensity of infections, according to the study. Moreover, shorter, warmer winters will mean more mosquitoes will survive.

“Where the number of temperature-suitable months of the year increase, so too will the winter months decrease, lowering the threshold for overwintering survival of the mosquitoes,” Ryan said. “We already have evidence, for example, in New England, that tire piles can provide sufficiently ambient overwintering habitat already for albopictus, by virtue of retaining pooled water that doesn’t get too cold. With fewer months at those very low temperatures, the pressure on survival is lessened, and more overwintering mosquitoes will make it to the next season.”

Humidity and water are crucial for vector breeding.

Pixabay

The scientists’ goal was to better understand what increasing temperatures would mean for the handful of viruses that Aedes mosquitoes spread. “We used a model of virus spread at different temperatures to mark out where in the world these viruses might be over time, and used climate models to map people at risk now and in the future, that is, 2050 and 2080,” Carlson explained. “This study is a bit of a numbers game: with 7 billion people on Earth, who’s most at risk now? Who’s at risk in a generation? We don’t know where mosquitoes will be in the future. What we can do is say where they might be able to transmit viruses if they show up.”

The burden on developing countries, already hard hit, likely will increase, especially in the East African portion of sub-Saharan Africa, “one of the top regions to experience increases in people at risk,” Ryan said. “These are regions in which we tend to focus on malaria and malaria control … However, we know that there is also dengue circulating in these regions. It is essential to think about surveillance of these diseases now. This is a part of the world that will be facing the intersection of multiple vulnerabilities under climate change, with underfunded infrastructure to manage multiple health impacts.”

Regions most impacted by Dengue worldwide, 2015.

Dengue, which causes high fever, headache, and joint pain, is the most common vector-borne viral disease in the world, with up to 100 million infections and 25,000 deaths annually, and, in recent years, has appeared in the U.S. It caused an epidemic in Hawaii in 2001, as well as a cluster of cases in Florida about ten years ago, with additional sporadic infections since then. It also has shown up with increasing frequency along the Texas-Mexican border.

The 2009 Florida cases, in fact, were the first dengue cases acquired in the continental U.S. — outside of the Texas-Mexico border — since 1945, and the first locally transmitted cases in Florida since 1934. “We’ve seen dengue showing up in Hawaii and Florida, then we saw Zika arrive in Florida and really grab public attention,” Ryan said. “Because Aedes aegypti is such a globalized mosquito, the potential for it to facilitate new outbreaks of many diseases is high.”

Often, cases that arise in the U.S. typically result after Americans travel and are infected abroad. Once they return home, a local mosquito bites them and acquires the virus. It then can transmit it to others. “Travelers overseas can bring back pathogens that can establish in local mosquito populations,” Ryan said. “This potential is a very real issue.”

Estimated potential range of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in the U.S. Maps do not represent risk for spread of disease, 2017.

There are several thousand species of mosquitoes, but only a few transmit disease. Anopheles mosquitoes carry the parasites that causes malaria and filariasis — also called elephantiasis — and the virus that causes encephalitis. Culex mosquitoes carry encephalitis, filariasis, and the virus that causes West Nile, while the two Aedes species studied in this paper transmit the viruses that cause yellow fever, dengue and encephalitis.

“We’ve only managed to capture the uncertain futures for two mosquitoes that spread a handful of diseases — and there’s at least a dozen vectors we need this information on,” Carlson said. “It’s very worrisome to think how much these diseases might increase, but it’s even more concerning that we don’t have a sense of that future. We have several decades of work to do in the next couple years if we want to be ready.”

He believes that climate mitigation could save millions of lives, “but I also don’t want us to fall into the trap of mitigating climate change just to keep dengue and Zika in the tropics, and out of the U.S. and Europe,” he said. “Facing something as massive as climate change gives us a chance to rethink the world’s health disparities, and work towards a future where fewer people die of preventable diseases like these. Facing climate change and tackling the burden of neglected tropical diseases go hand-in-hand.”

Reposted with permission from our media associate Nexus Media.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe