Ticks and Mosquitoes Bringing More Diseases—What Can We Do?

By Joyce Sakamoto and Shelley Whitehead

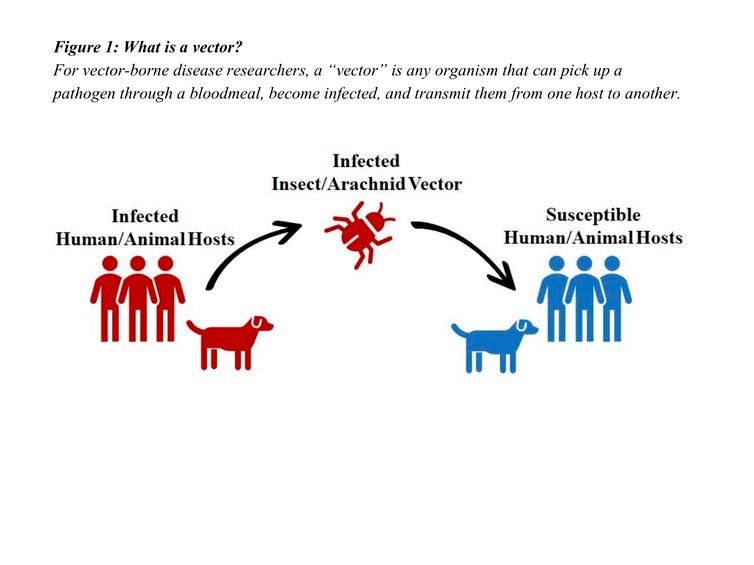

Cases of vector-borne disease have more than doubled in the U.S. since 2004, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently reported, with mosquitoes and ticks bearing most of the blame.

Mosquitoes, long spreaders of malaria and yellow fever, have more recently spread dengue, Zika and Chikungunya viruses, and caused epidemic outbreaks, mainly in U.S. territories. The insects are also largely responsible for making West Nile virus endemic in the continental U.S.

Ticks, which are not insects but parasitic arthropods, actually cause more disease in the U.S. than mosquitoes do, accounting for 76.51 percent of total U.S. vector-borne disease cases. These include Lyme disease and Rocky Mountain spotted fever and newer diseases as well.

Why the uptick in vector-borne disease, and more importantly, how can we protect ourselves from potentially serious diseases? As researchers of these types of diseases, we have some answers.

Blood: The High Cost of Living

Both mosquitoes and ticks transmit disease-causing pathogens through bites.

Shelley Whitehead

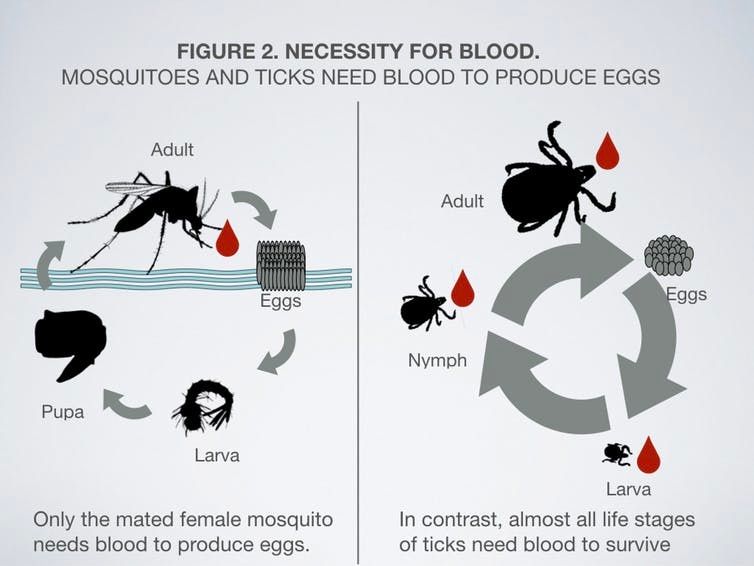

Only the female mosquito takes a blood meal to make eggs, but almost all life stages of ticks need blood to survive.

Joyce Sakamoto

Although mosquitoes were first demonstrated to have the ability to transmit diseases in 1889, mosquitoes have been transmitting diseases for far longer. Written records as early as 2700 B.C. suggest malaria plagued humans in China.

The first suspected dengue outbreak occurred in the early 1600s, but it took three centuries for the first three mosquito-borne diseases—malaria, dengue and yellow fever—to invade the Americas. Yet, in the past two decades alone, we’ve experienced a wave of three more mosquito-borne diseases—West Nile, Chikungunya and Zika viruses. This marked increase in disease spread is due to several factors, including advances in air and water travel and warming temperatures.

The High Cost of International Travel and Trade

The international tire trade has made Aedes albopictus, the Asian tiger mosquito, a global traveler. This mosquito gains passage on cargo ships and gets unlimited access to man-made containers, which it needs for breeding, in the thousands of tires on board these ships. Rainwater collecting in the tires are ideal breeding sites. Even though it is not a major vector of dengue, Chikungunya and Zika viruses, this invasive species is still especially dangerous. It is able to outcompete most other mosquito species that live in similar habitats.

We humans serve as hosts for many vector-borne diseases, and our own movement can aid transmission. We can hop on a plane and be in a different country within hours. Diseases once quarantined to other regions of the globe can now be easily transported within an infected human. Some people don’t even realize they are sick. Researchers have estimated that up to 80 percent of individuals infected with Zika virus are symptomless. Yet, if the right vector feeds on a symptomless but infected person, transmission can still occur.

Increased climate fluctuations, largely due to human activity, can also affect how vector-borne diseases spread. Warmer climates may allow mosquitoes to survive in areas previously too cold to support them.

Predicting the outcome of warming on overall vector populations can be difficult. If, for example, summer in the deep Southeast becomes too hot and dry for mosquito development, peaks in transmission and mosquito numbers could shift to the fall. Higher temperatures may shorten the time it takes for pathogens to develop within mosquitoes, so mosquitoes may become infectious faster and transmit pathogens sooner.

Tick-Borne Diseases

Five percent of 900 tick species are known to transmit disease-causing microorganisms. Because 38 percent of all tick species have been known to bite humans, researchers will likely find more tick-borne diseases. Since 2004, there have been nine new vector-borne diseases described in the U.S., and seven of these are tick-transmitted, including the two potentially fatal Bourbon and Heartland viruses.

Most, or 82 percent of tick-borne disease cases, are Lyme disease, which is caused by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi, and transmitted by the blacklegged, or deer, tick. Cases of Lyme, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, babesiosis, anaplasmosis and ehrlichiosis have increased two-and-a-half to six-and-a-half fold.

Tick-borne diseases may be rising due to global travel, animal transport, habitat fragmentation and changing climate. Climate change is correlated with range expansion of several important tick species. Ticks previously limited by cold winters are now becoming established farther north. In response to the arrival of Lyme disease to Canadian soil, the Public Health Agency of Canada responded with a Federal Framework on Lyme Disease focused on disease surveillance, education and awareness, and best practices for control, prevention and treatment of Lyme disease.

What Can You Do?

To lower your risk of transmission from mosquitoes:

- Check backyards for anything that could hold water and empty such vessels. This includes children’s toys, bird baths, empty soda cans and flower pots.

- Use mosquito repellents that are EPA approved. Avoid natural repellents that haven’t been verified for their effectiveness.

To prevent tick bites:

One sure way to prevent tick bites is to avoid suitable habitats for ticks, but this isn’t always possible. Large-scale habitat control or acaricide (tick-killing) treatment of wildlife, though possible, can be difficult or not cost-effective for homeowners. The best preventative measures are:

- Use CDC-recommended repellents such as DEET or picaridin.

- Shower and do a thorough tick check.

Joyce Sakamoto

Tick checks are absolutely crucial. People usually follow this routine after going outdoors, but sometimes forget. And they often avoid places that ticks love, such as between your legs. Hard-to-reach areas are prime real estate for blood-feeding parasites that don’t want to be dislodged, so make sure to check: the hairline (especially on children), torso, belly button and groin. If necessary, get assistance or a mirror and a bright light.

If you find an embedded tick, correctly dislodge it with fine-tipped tweezers, grasping the part closest to the skin and pulling straight up. Do not burn, squeeze, twist or smother the tick, since this may cause it to regurgitate. Gross-out alert: Any pathogens they have in their saliva can then be dumped into the bite site.

After removal, keep the tick for identification; different species transmit different pathogens. Finally, see a doctor after finding an embedded tick or if you think you have been bitten. In addition to getting medical attention, your data will be added to the national list of reported tick-borne diseases.

The CDC has several pages dedicated to vector-borne disease control and prevention. Local state health departments, general practitioners and veterinarians will also have recommendations for prevention, treatment and vector control. Talk to your veterinarian about repellents or agents that will kill mites called acaricides for pets, since some can be toxic to cats.

#EPA Approves Release of Mosquito-Killing #Mosquitoes in 20 States https://t.co/FYN3EBTLz7 @SierraClub @GMWatch @greenpeaceusa @foe_us @foodandwater @NRDC @OrganicConsumer @350 @LeoDiCaprio @SenSanders

— EcoWatch (@EcoWatch) November 8, 2017

Reposted with permission from our media associate The Conversation.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe