The official number of moose in Yellowstone National Park is 200. Unofficially, rangers told me that it could be as few as 80 animals. In other parts of the country, Minnesota has seen a dramatic decline in their moose population of 70 percent from 2006 to 2013, while in New Hampshire, 3,800 animals remain of the 7,500 present in the late 1990s.

There’s no question about the cause. Warmer winters have increased ticks in the North Woods, which can weaken moose. Some animals are carrying as many as 120,000 ticks. They are so highly infected that they become anemic from blood loss as the ticks engorge themselves on their hosts.

Other moose rub so vigorously against the forest trees to remove ticks that they lose much of their characteristic dark brown coat. They’re known as “ghost moose” for the pale skin that’s revealed. That makes them more visible to predators and less able to cope with the cold winters in their environs.

Moose calf mortality is high, too. In New Hampshire, 75 percent of moose calves died from ticks over the winter of 2015-2016, while Maine’s mortality rate was 60 percent.

Parasites, including brainworms (Parelaphostrogylus tenuis), are also taking a toll. Liver flukes (Fascioloides magna) and tapeworms have also been found in necropsies of moose in Minnesota. The tapeworms, which are carried by wolves, can fatally clog the lungs of a moose.

“Moose are under a firing line of things that are affecting their population,” said Dr. Seth Moore, director of biology and environment for the Greater Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. “And I think ultimately that all these different things that are affecting the moose population are driven by climate change.”

Speaking on a CBC documentary produced in 2015, Moore predicted that Minnesota moose could be gone in 50 years.

The National Wildlife Federation (NWF) also links the plight of moose to climate change.

“Heat affects moose directly, as summer heat stress leads to dropping weights, a fall in pregnancy rates, and increased vulnerability to disease,” the NWF explains. “When it gets too warm, moose typically seek shelter rather than foraging for nutritious foods needed to keep them healthy.”

Referencing New England’s now-shorter winters, the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department wistfully says, “The best ways to reduce the impacts of winter ticks would be to add back the three weeks of winter.”

Moose populations are now a managed resource in most states. According to the NWF, 56,000 people hunt in New Hampshire and 630,000 enjoy wildlife watching. There is often a conflict between those who want to hunt moose and those who simply want to watch them. As a result of the decline in moose in Minnesota, hunting was suspended indefinitely in the state beginning in 2013.

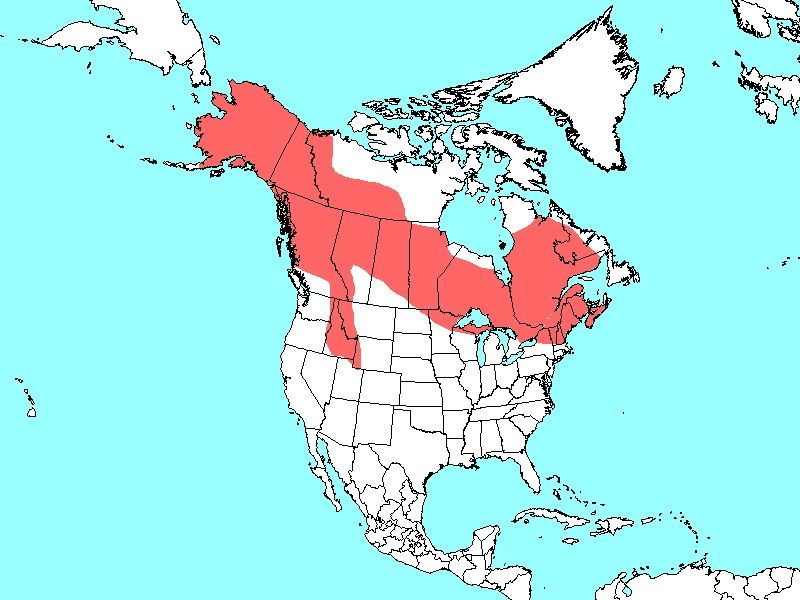

Overhunting decimated populations in the lower 48 states by the late 1800s, but conservation efforts enabled them to recover. Moose are listed as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. They cite a 2011 population of about 1 million in North America. However, other sources differ. There are no standardized national or international monitoring programs. Populations in any one area can change dynamically due to local conditions such as forest fires, unusually warm or cold winters, introduction of predators or new infestations.

In Maine, where I live, there’s a healthy population of 60-70,000 moose—the largest in the lower 48 states. The state will issue 2,160 hunting permits this year, for a one-week season in late October.

The Penobscot Nation, who hosted me on their tribal lands last week, have a traditional story about a giant monster moose in a large lake. The Creator, Glooksap, slays the moose and eats it. He turns his kettle over and leaves it by the lake, where it turns into stone and is now the place known as Mount Kineo, in Moosehead Lake. The story points Penobscot hunters to a place were moose are abundant—even today—enabling them to feed their families. It was with this knowledge that I partook of the warm moose stew they fed me on a raw September evening along the Penobscot River. For the Penobscot, nothing is taken from the land without thanking Mother Earth.

Moose is an Algonquin term for “eater of twigs.” An adult moose can consume 40 to 60 pounds of leaves, twigs and buds each day. In summer, they frequent ponds and lakes to feed on sodium-rich aquatic plants. Winter can be harsh, particularly where deep snow makes movement difficult. Average lifespan in the wild is 10 to 12 years. Black bears, along with mountain lions and wolves, where present, are predators, and coyotes may take some young calves.

Forest fires can benefit moose in certain circumstances. By creating open burned areas, more edge habitat is available for foraging. Moose may return to burned areas several months after a fire, leading to population density increases of five or six fold. Populations in a post-burn area will peak 10 to 30 years following the fire.

However, large fires may be followed by changes in the vegetation that replants the affected areas.

“Some burns produce a grassland stage; others come back in pure spruce; many produce aspen with little birch or willow which are the most palatable and productive browse plants,” says a 2010 study by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“Where can I see a moose?” is an oft-asked question by tourists to Alaska, Yellowstone, Northern New England and other areas where they can be found. Encountering one of these large, long-legged mammals in the wild is an event not soon forgotten. Future encounters may be fewer due to the risks created by climate change.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe