Rebecca Burgess came up with the idea of a fibersheds project to develop an eco-friendly, locally sourced wardrobe. Nicolás Boullosa / CC BY 2.0

By Tara Lohan

If I were to open my refrigerator, the origins of most of the food wouldn’t be too much of a mystery — the milk, cheese and produce all come from relatively nearby farms. I can tell from the labels on other packaged goods if they’re fair trade, non-GMO or organic.

But if I were to open my closet, it’d be a different story. I know shockingly little about where the clothes I own come from, what chemicals went into making them, or how far they may have traveled.

In recent years the idea of eating from our own local foodsheds has become more popular, but can the idea of locally sourcing things we use be taken beyond food?

Rebecca Burgess wondered that, too. A trained weaver and dyer, she came up with the idea of a fibersheds project about 10 years ago to develop an eco-friendly, locally sourced wardrobe.

The project led to the establishment of a nonprofit, Fibershed, to put some of her experiences into practice. Now Burgess has expanded it even more in her new book, Fibershed: Growing a Movement of Farmers, Fashion Activists and Makers for a New Textile Economy.

As Burgess writes, we’re still a long way from local fibersheds supplying our clothes, but fixing that paradigm is the focus of the book.

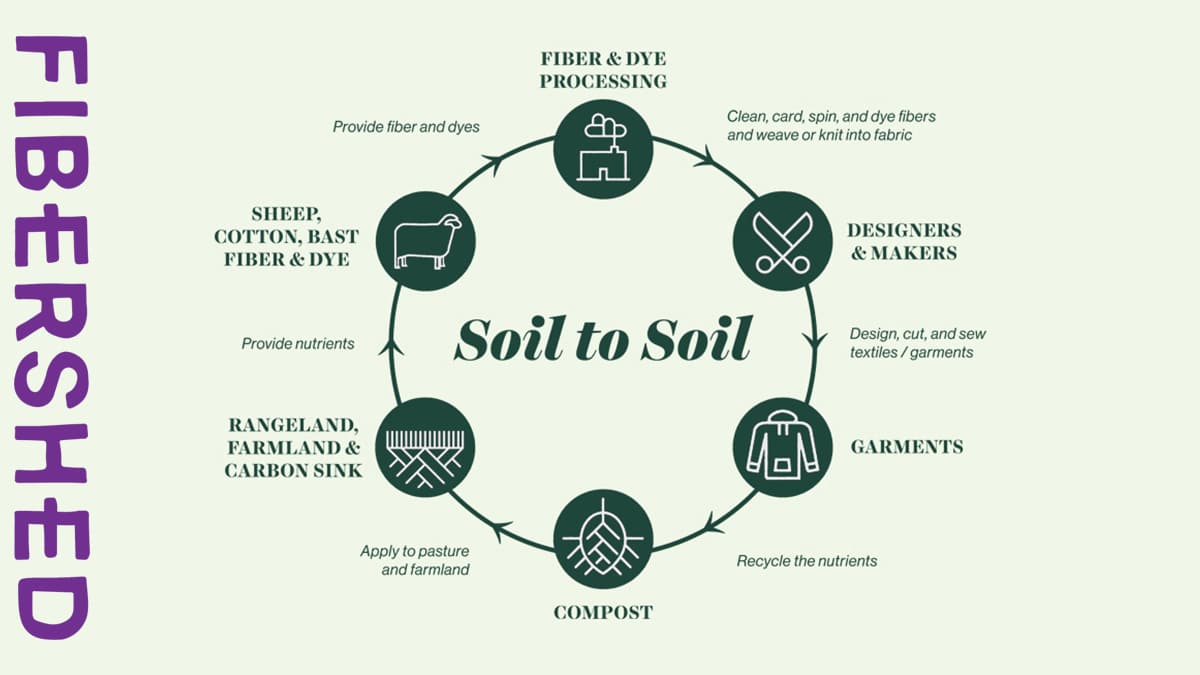

Burgess describes fibersheds as “place-based textile sovereignty … focused on the source of the raw material, the transparency with which it is converted into clothing, and the connectivity among all parts, from soil to skin and back to soil.”

Essentially, it’s knowing a lot better where your clothes come from. But it’s also about disconnecting from a harmful system and reinvigorating a local, place-based economy where the process of “farm to closet” is beneficial for the environment and all the people involved in the supply chain.

The main focus of the book is explaining the tough work of how to create a fibershed, but she starts with why we need one to begin with. And it’s a pretty convincing picture.

“The [textile] industry utilizes thousands of synthetic compounds, often in various combinations to soften, process and dye our clothing, many of which are linked to a range of human diseases, including chronic illnesses and cancer,” she writes.

About 98 percent of the clothes sold in the U.S. are made overseas, many in factories where workers face dangerous conditions. These days we also buy more clothes than we have in the past, and we keep them for less time. “Fast fashion” — clothes designed to last just two weeks before being thrown away — is a real thing. And a real problem.

The entire textile economy — much like the industrial food economy — is bad for people and the planet.

So what do we do about it? Burgess spends most of her book focusing on how to build the infrastructure to produce the materials we need locally, ethically and sustainably. And she doesn’t skirt around the fact that this is really tough to pull off.

As she found in her initial year-long project, getting local clothes is not nearly as easy as getting local food because the materials for clothes need to be processed in multiple stages. That takes specific equipment and skilled labor — something in short supply in the U.S. these days.

Take cotton, for example.

Burgess’s home state of California still grows a lot of cotton, but most of it is shipped overseas for combing and spinning, and then to be cheaply made into clothes. And what’s grown here is almost all genetically modified.

“Global-scale commodity systems have done a very good job of making it harder and more expensive to purchase a locally grown cotton T-shirt than it is to drive to a box store and purchase an equivalent garment grown and constructed on several different continents,” she writes.

That doesn’t mean the system can’t be changed. Doing so means supporting existing farmers and helping them transition to more climate-friendly farming practices, she says. Burgess weaves a whole chapter about how good farming techniques can help build healthy soil, an important component for making the most of water resources (which can be sparse in California) and helping to sequester carbon.

Chelsea Green

As an example she points to California grower Sally Fox, who breeds naturally colored cotton (apparently not all cotton is white) in the Capay Valley and implements soil-building farming practices rotating cotton with heirloom wheat and a flock of Merino sheep.

Burgess also stitches together examples of other plant and animal-based fibers being used in her region of Northern California and explains why they can help supplant the need for synthetic and chemical-based fabrics we mostly rely on now.

There’s flax, which produces linen, and is best suited for growing during California’s rainy season when farmers don’t need additional irrigation water. And of course the use of water-thrifty hemp has experienced a resurgence since most restrictions on farming and selling it have been lifted.

And then there are a litany of animal fibers. In her region in Northern California alone, she writes, there are around 20 different types of sheep being raised, as well as Huacaya and Suri alpaca, mohair goats, llamas, Angora rabbits and guanacos (a close relative of the llama).

But finding the fiber is just one part of the equation. Processing all of this raw material — each of which requires different techniques — is the biggest obstacle.

California produces 3 million pounds of wool a year but has the milling capacity for just 10,000 pounds. That’s a very big gap to close — but Burgess and her collaborators are trying. They have a plan for a “closed-loop manufacturing model” that will help bring the right milling equipment close to home and connect it to local producers and artisans. But it comes with a price tag of million.

Every fibershed is likely to have different costs depending on local materials, equipment and expertise, but they all face the same conundrum: How do you produce enough locally sourced materials to fund the systems to make even more locally sourced materials?

In order to move forward projects like this one in Northern California and in other communities around the country, we’ll need vastly more demand and real commitment from clothing companies and retailers. There’s less in the book specifically focused on how consumers can actively help drive that process. But there are ample resources if you want to learn more about what fibersheds are being developed where you live or how to engage in the process yourself. Don’t expect the book to read like a “how to” manual, though. It’s more of a thoughtful discussion of issues, obstacles and solutions, including meeting on-the-ground farmers and producers who are putting these practices to work.

At the very minimum the book has made me rethink virtually everything my closet, and even a shift in consuming thinking at this point seems like a step in the right direction. Supporting fibersheds may not be as simple as shopping at farmers markets instead of box stores, but Burgess drives home the tremendous value in just trying.

Her yearlong local clothes experiment 10 years ago, for example, led to new friendships and the launch of four new businesses. Engaging in this kind of process, she writes, creates “opportunities to build new relationships that are rooted in sharing skills, physical labor, and creativity, all of which carry meaning, purpose, and a way to belong to one another and to the land.”

That’s the perfect antidote to “fast fashion” and a reminder that our allegiance to a disposable, throwaway culture — the one that produces plastic bottles, flimsy T-shirts and weak interpersonal relationships — is what needs to be tossed.

Tara Lohan is deputy editor of The Revelator.

Reposted with permission from The Revelator.

- 5 Tips for a More Earth-Conscious Wardrobe - EcoWatch

- Ashley Biden Shows Ivanka Trump How to Make American Fashion ...

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe