By Ajit Niranjan

The lizards are frantic and the turtles plodding, but both scrabble to escape the perspex containers that hold them. The reptiles, some in small boxes and fetching prices of up to thousands of euros, are on sale at the Terraristika — Europe’s largest reptile trade fair and a suspected wildlife-trafficking hub.

Thousands of enthusiasts descend on the German city of Hamm four times a year to buy exotic creatures ranging from coin-sized glass frogs to tarantulas and venomous snakes. In the wild, some of these animals are becoming dangerously scarce.

As well as the physical marketplace, the Terraristika is a center of a global online community of reptile traders and hobbyists. Customers browse animals on the web and collect them at the fair, sometimes on the unsupervised fringes of the event. Sellers arrange pickups via Facebook groups, owners share care tips on internet forums and YouTubers post videos of themselves “unboxing” animals bought at fairs.

In Germany, live reptiles make up the majority of wildlife traded online, a report into wildlife cybercrime by conservation group International Fund for Animal Welfare found in 2018.

The researchers found most adverts in internet forums, not social media, but they also saw closed Facebook groups with names suggesting they are used to trade reptiles.

Visitors to the Terraristika can buy all kinds of reptiles, including snakes.

DW also found endangered reptiles for sale in Facebook groups such as ‘Terraristika Hamm — “MARKTPLATZ”‘ and ‘Hamm and Houten Reptile Classifieds.’

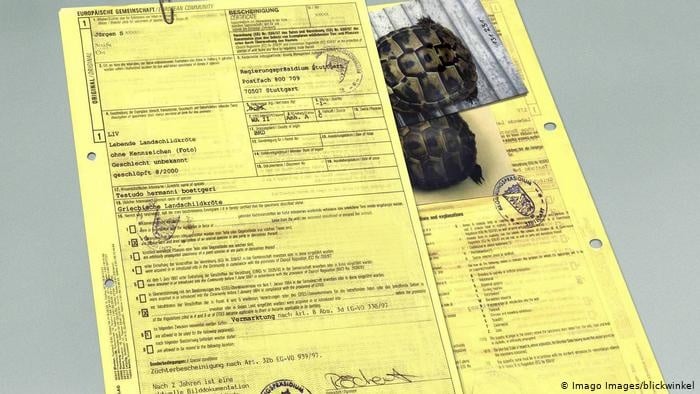

Some of the species on offer are listed under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), an agreement signed by 183 countries that restricts trade in threatened wildlife. The animals were not necessarily poached — specimens of endangered species are often bred in captivity — but conservation groups fear that, because online trade is so difficult to regulate, endangered animals are being trafficked online.

In one group, a buyer complained that lizards he’d bought over Facebook didn’t survive being delivered by post. “Pay me 1200 euro [sic],” he wrote in a private message to the seller accompanied by a laughing emoji, a screenshot of which he posted in the group. “You sent dead animals.”

Hiding in Plain Sight

Facebook refused multiple requests for comment. Confronted with screenshots, a spokesperson from a PR firm acting on the company’s behalf thanked DW for “sharing the examples of groups advertising endangered animals.” Facebook then deleted the groups.

Facebook’s commercial policy states that posts may not promote the sale of animals. It is a member of the Coalition to End Wildlife Trafficking Online, a partnership between internet companies and conservation groups, along with tech giants such as eBay, Baidu and Google.

But conservation groups fear the ease with which live animals can be bought on Facebook and other platforms has opened up the market for smugglers. Online wildlife trade is an “extreme problem” because it makes endangered animals available to “every normal person,” said Katharina Lameter, a biologist at conservation group Pro Wildlife.

Some reptiles traded online are subject to bans or regulations under the CITES convention.

“That means anyone can advertise, there can be an incredible number of species on offer and anyone can buy these animals without ever having seen them. Often the animals are shipped off or picked up at reptile trade fairs,” Lameter told DW.

Unlike drugs or weapons, wildlife is rarely traded on the darknet, a corner of the internet used to anonymously buy illegal goods — and what does appear there is mostly body parts such as elephant tusks, rhino horns and pangolin scales. Live animals are scarce, with traders preferring regular platforms that have access to bigger markets.

“Cybercrime is under the spotlight because the internet is an easy platform to place and to offer illegal goods anonymously … including wildlife,” said Sergio Tirro, head of environmental crime analysis at Europol. “It’s easy to hide the financial flow by using a prepaid card.”

Legal Loopholes

Legal loopholes also cause headaches for law enforcement trying to catch traffickers in the act. For instance, Germany is at the center of the illegal trade in Sri Lankan reptiles, according to an investigation published in April by wildlife trade monitoring group TRAFFIC.

More than half of Sri Lankan reptile species are threatened and the government has banned the export of almost all live reptiles. But they are not all protected internationally under CITES, meaning animals smuggled over in violation of Sri Lankan law can be freely traded in Europe.

Traffic found species “extremely vulnerable to overexploitation” being sold in Facebook groups and classified reptile forums. The number of online adverts offering endangered reptiles, including those endemic to Sri Lanka, rises in the run-up to the quarterly Terraristika fair.

Reptiles are popular pets and trade happens on and offline, like at this fair.

In the bustling warehouse where the Terraristika takes place, sellers eagerly describe their species’ “exotic” origins — Sri Lanka, Mexico, Vietnam — but say the specimens they offer were bred in captivity in Europe, not smuggled from abroad.

But with deals taking place in nearby car parks, hotel bars and under tables at the fair itself, authorities struggle to police this. Styrofoam boxes of reptiles change hands off-site before the fair has even begun. Traders who arrange car park deals over the internet need not register a stall with the Terraristika organizers or submit themselves to checks in order to find buyers.

Terraristika did not respond to a request for comment. In a public statement in August responding to questions from German news agency dpa, Terraristika said it works with authorities to prevent illegal activities, but was not responsible if animals were misclassified with false documentation, just as an antiques market could not guarantee vendors wouldn’t offer stolen goods.

Fighting Back

Yet the internet and digital media are also being used in the fight against illegal wildlife trafficking. Europol’s Sergio Tirro said customs officers often take photos of suspicious specimens and send them immediately to experts to identify. Reptiles such as turtles can have minor physical differences between species that are endangered and not.

“You don’t need to see the animal physically,” said Tirro.

“When you have very precise pictures you can detect it. You don’t need to travel all around the world to see if an animal belongs to a protected species.”

And not all internet platforms are affected. DW did not find reptiles for sale on eBay, which said its open marketplace does not lend itself to trade in living creatures because every posting is completely public. Conservation groups confirmed this.

Ebay said it uses algorithms to search for suspicious keywords and alert human enforcers who can remove them. Some terms such as ivory are automatically banned by block filters, so sellers receive a warning message as soon as they try to post an advert with a banned word.

It’s unclear if Facebook uses similar methods, but DW found several posts offering endangered species by typing the animals’ Latin names into the Facebook search bar.

Conservation groups encourage tougher rules and stricter enforcement from internet platforms. But they caution that as one platform cracks down on wildlife trade, traders simply move to others that are less regulated.

“It would be best if online trade in live animals were completely banned,” said Lameter from Pro Wildlife.

Reposted with permission from our media associate DW.

- How Social Media Often Supports Animal Cruelty and the Illegal Pet ...

- Facebook Suspends More Than 200 Environmental and Indigenous Groups - EcoWatch

- UK Announces First Live Animal-Export Ban in Europe

- Facebook Tackles Climate Misinformation in New Project - EcoWatch

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe