By Greg Muttitt

We welcomed last week the first step by the International Energy Agency (IEA) towards describing how energy would look for the world to meet one of the Paris Agreement goals, to keep warming well below 2°C. Specifically, it looked at emissions being limited enough to give a two-in-three chance of staying below 2°C.

The report was co-published by IEA and its clean energy counterpart, the International Renewable Energy Agency, and commissioned by the German government. The two agencies are also working on a 1.5°C scenario, to be published in June.

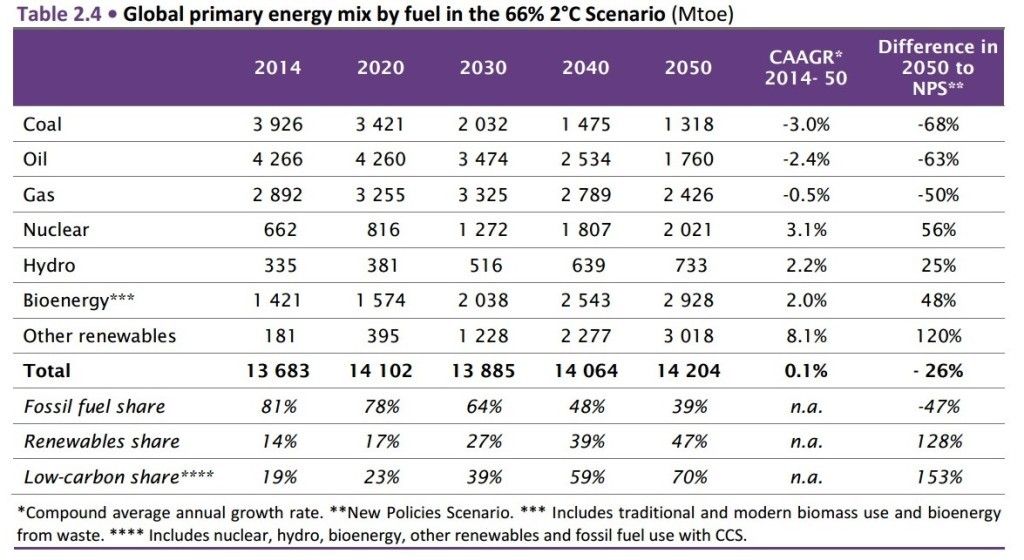

But there’s a problem with the IEA’s new climate scenario: It describes a slower decline in fossil fuels than our analysis of what the climate science actually requires. Here’s the key table:

Remarkably, the IEA foresees significant coal use in 2050 and gas barely declines from current levels. Let’s look at how the IEA reaches this outcome.

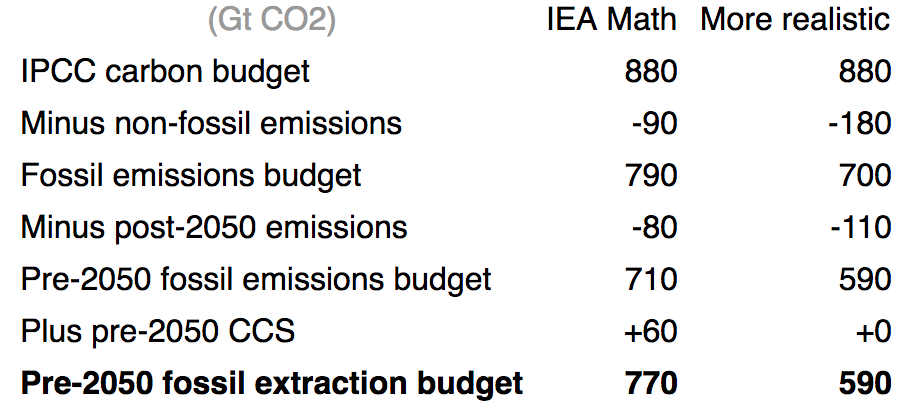

The new report starts off well: It takes the carbon budget from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, as we did in our report The Sky’s Limit: 880 gigatons (Gt) of carbon dioxide can be emitted from 2015 onwards. But the IEA then does three things that inflate the space for fossil fuels within that budget:

- It understates the potential non-fossil fuel emissions (primarily cement and land use emissions);

- It assumes a major breakthrough in carbon capture and storage (CCS);

- It allocates a disproportionate share of the carbon budget to the pre-2050 period—deeper emissions cuts are hidden outside the period of study.

The combined effect is to inflate the emissions from fossil fuels by about 180 Gt—the equivalent to running an extra 1,500 coal plants from 2015 to 2050. Here’s how the math works:

Disappearing Non-Fossil Emissions

The 880 Gt carbon budget is the total cumulative amount of CO2 that can be emitted from all sources in the future. While fossil fuels are the largest source of CO2 emissions, they are not the only source. The others are the calcination reaction in making cement and land use changes (such as agriculture and deforestation). So an estimate of these other sources must be deducted from the budget, to see how much room is left for fossil fuel emissions.

The IEA’s estimate of land use emissions (zero) is only slightly smaller than ours: We estimate 20 Gt over the century (when you take into account absorption of CO2 as well as emissions—based on a median of IPCC scenarios).

But the IEA assumes only 90 Gt of cement emissions over the century. Cement emissions are current 2 Gt per year; the IEA scenario projects them peaking in the 2020s and falling to 1 Gt by 2050, due to material efficiency and CCS. Our estimate is 160 Gt, based on an optimistic reading of the IEA’s own figures. The difference can only be squared with a very optimistic assumption on CCS, to which we turn next.

So the IEA assumes that only 90 Gt of the carbon budget must be deducted, leaving 790 Gt for fossil fuels. Our already-optimistic assumptions would require 180 Gt to be deducted and it could be a lot more than this. So at 790 Gt, fossil fuels are getting too much of the global carbon budget.

Burying Carbon Out of Sight

The new IEA scenario assumes that CCS will be quickly ramped up in the 2020s, capturing 3 Gt per year of fossil fuel emissions by 2035, not counting the more than 1 Gt per year of cement emissions.

This seems highly unlikely, given that both companies and governments (including the UK and the U.S.) have pulled out of investing in CCS in the last couple of years. The IEA itself has noted that “deployment has stalled.” A major reason is that CCS-equipped coal or gas power—while obviously attractive to the fossil fuel industry—is significantly more expensive than wind or solar power. The IEA does not explain how it expects a turnaround to occur.

The IEA sees more than 600 GW of CCS-equipped power plants being installed by 2050, equivalent to nearly 20 percent of today’s coal and gas capacity. Given the long life of power stations, the IEA believes a significant portion of this will be achieved by retrofitting existing plants—which is even more expensive than installing CCS in new plants.

The effect of the IEA’s CCS assumption is to inflate the available carbon budget by around 60 Gt before 2050 and up to 200 Gt over the century, based on an expensive technological fix that has no track record to date.

Hiding Emissions Cuts Off the Page

The new report describes the energy system from 2015 to 2050. But the carbon budget stipulates how much the world can emit over all time (until atmospheric concentrations stabilize). So a key part of IEA’s calculation is to decide how much of its 790 Gt budget to allocate before 2050 and how much after. The IEA opts to save just 80 Gt of the budget for post-2050 and 710 Gt for pre-2050.

This would require a sudden change in the rate of emissions once we reached 2050, as the graph shows.

Since the scenario forecasts only up to 2050, it understates the emissions reductions—and overstates fossil fuel use—during that period. Like a magician’s trick, the real action is happening out of sight.

If emissions fell at a steady rate after 2020, rather than postponing some reductions until after 2050, they would have to decrease by 5 percent per year. On this basis, the IEA’s pre-2050 carbon budget for energy would fall from 710 to 635 Gt. Compounding this with our more reasonable assumption on non-fossil emissions, we would start with an all-time budget of 880 – 180 = 700 Gt. Reducing emissions at a constant rate after 2020 would allocated 590 Gt of this to pre-2050. In comparison, the IEA has taken a pre-2050 budget of 710 Gt and inflated it with CCS to about 770.

The IEA’s three distortions buy an extra 180 Gt for fossil fuels (see table). Over the 35 years of the scenario, that’s the equivalent of an extra 1,500 average-sized coal plants.

Wrong Conclusions

Without these distortions, the IEA would reach the same conclusion that we did in the Sky’s Limit: that there is no room for new fossil fuel development. Instead, it calls for new investment in fossil fuels—including $200 billion a year of investment in fossil fuel extraction as late as 2050—investment that will either be wasted or will drive devastating climate change.

Governments and investors routinely use IEA scenarios to inform energy decisions, especially the scenarios in its flagship World Energy Outlook, published every November. But as we’ve seen, even in its new climate scenario, the IEA overstates the future of fossil fuels, due to flawed assumptions and hidden distortions.

It is time for the IEA to come clean. First, the IEA must drop its outdated 450 Scenario and replace it with one in line with Paris. Second, it must fix these distortions, to give a clear picture of the action that’s really needed.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe