Scientist at Work: Identifying Individual Gray Wolves by Their Howls

By Angela Dassow

Love them or hate them, wolves are vital members of natural ecosystems and the health of a wolf population can be an important factor in maintaining balance among species. Wolf populations are growing in North America—the Great Lakes region in particular now supports more than 3,700 individuals. Keeping track of wolf pack movements is important for reducing human-wolf conflicts which can arise when packs move too close to ranches.

The traditional way to track wolves involves setting traps, sedating and then radio-collaring individual animals. While effective, this approach is time intensive and expensive, and entails risks for the animals.

I was fortunate to participate in this entire process firsthand as an undergraduate student. During the summer trapping seasons, I became familiar with each of the wolves in the central forest region of Wisconsin. This experience led to several conversations with the wildlife biologists in the area about whether wolf howls could be used to help identifying non-radio-collared pack members.

This question remained a fun thought experiment for many years. Now as a biology professor who specializes in bioacoustics, I’ve been able to turn that thought experiment into a full research question: Can we use acoustic features to identify individual wolves in the wild?

Downsides of Radio Collaring

Because of the many challenges involved in radio collaring an animal, it would be useful to have a new way to identify and track wild wolves.

A U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service employee fastens a radio collar onto a sedated female gray wolf. Lori Iverson / USFWS / CC BY

To successfully set a trap, wildlife managers must first spend days, if not weeks, scouting for signs of wolves. Once they’ve identified a suitable area, they set traps that must be checked every 24 hours. If successful, the animal needs to be sedated before it can be removed from the trap—which can be stressful both for the wolf and the researchers involved.

A sedated wolf cannot regulate its body temperature and overheating can become an issue on hot days. Human handling of a sedated wolf can also be stressful on the pack members that are often nearby, observing the scene. Even after an animal is successfully radio-collared and released, it’s still vulnerable to predators while the sedative wears off.

In spite of these risks, radio-collaring has been the standard way to track populations because each collar’s radio-transmitter frequency acts as a unique identifier of an individual. Researchers can then use aerial surveys where a pilot searches for the collared animal or ground surveys where a field crew drives throughout a pack territory searching for feedback from the radio signal. This method is used to track a wide array of animals, including turtles, birds, bats, whales, fish, snakes and more.

Angela Dassow and Cara Hull survey a road in central Wisconsin for signs of wolves. Caitlin McCombe / CC BY-ND

Listening to Learn Who’s Who

In 2013, behavioral ecologist Holly Root-Gutteridge and her colleagues successfully demonstrated that they could identify individual wolves in captivity using acoustic features. Their research provided evidence that it made sense to test whether vocal identification in wild animals is possible.

So with the support of the Summer Undergraduate Research Experience at Carthage College, volunteers from the Timber Wolf Information Network, and wildlife managers at Sandhill Wildlife Area in Babcock, Wisconsin, my undergraduate students Cara Hull and Caitlin McCombe and I began to record wolves in the wild.

It would be an understatement to say fieldwork can be challenging. On any given day, there can be daunting weather fluctuations. Biting insects, especially mosquitoes and deer flies, are abundant in wolf habitat. We had to constantly check ourselves for ticks. And then of course comes the actual fieldwork.

Wolves naturally avoid coming near people, but the best quality recordings are made up close to where the animals are producing the sounds. To get close with our audio equipment, we had to track the wolves every day to learn where they’d most recently been within their large territories. That’s how we’d establish a starting point for our nightly recording sessions.

Fresh track from an adult gray wolf. Angela Dassow / CC BY-ND

Conducting a daily survey of wolf habitat requires driving or walking down every possible path within a wolf’s territory. Signs of activity could include fresh footprints or tracks. This can tell us how many animals were in the area and what direction they were heading.

Large dogs can produce footprints that are similar in size to those of wolves; but the pattern of tracks can be distinguished based on the placement of their feet and the directness of the chosen route. Dogs have a tendency to wander more, while wolves will walk in a more efficient straight line.

In addition to tracks, we conduct a survey of fresh scat. It’s not glamorous, but examining their feces provides valuable information about what the wolves have been eating and how recently they walked along a trail.

Carthage College biology students Cara Hull and Caitlin McCombe conduct a howl survey in central Wisconsin. Angela Dassow / CC BY-ND

Using the information from our daytime survey, we plan a shorter nighttime howling route. Howling is a natural behavior during the evenings, when wolves call to signal that a territory is occupied. At each stopping point on our route, a researcher must get out of the vehicle and howl while another researcher records with a microphone any wolf responses, announcing their presence or defending territory. If we are successful in eliciting a response, we continue in its direction until we get as close as possible.

Use of lights is discouraged since it can deter the wolves from calling again, so we needed to feel our way through the forest at night. Personally, I think it is incredibly exciting to be walking down a trail in the dark and have a wolf walk within feet of where I am. It may sound scary, but we are not in any danger since wolves prefer to avoid contact with humans. During our month-long survey, we were fortunate to experience two close wolf encounters.

Back in the Lab, Analyzing the Calls

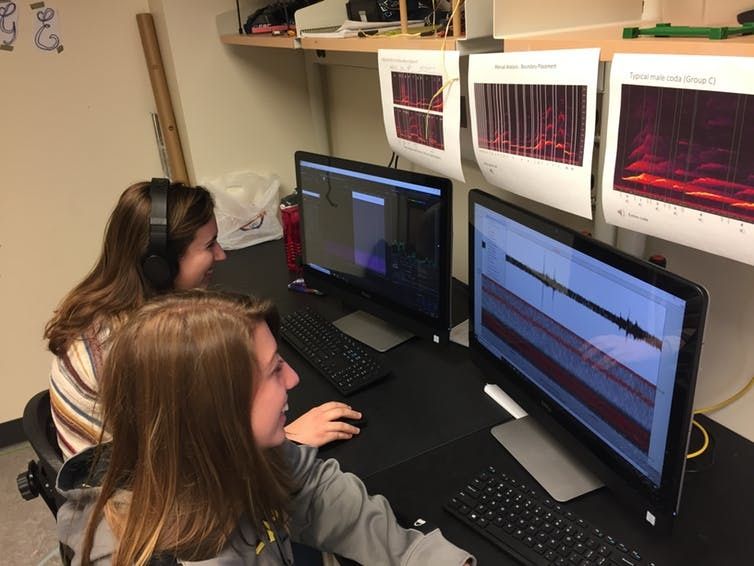

With the howls recorded, we can return to the lab to analyze our findings using audio software.

Acoustic properties are measured using Adobe Audition. Angela Dassow / CC BY-ND

We were able to isolate 21 howls from two adult wolves over two evenings. For each howl, we made six types of frequency measurements and two types of duration measurements. Frequency is how high or low the pitch of the howl sounds and duration is the length of time the howl lasted.

For wild gray wolves, we found that the maximum frequency—that is, the highest sound an animal produced—and the frequency at the end of the howl were the two variables that were most individualistic. For captive wolves, it was different. The lowest frequency an individual produced—what in acoustics is called their fundamental frequency—and the loudness of its calls were the factors that best differentiated among the captive individuals.

The differences in useful identification information between wild and captive howls are likely a reflection of signal quality. The captive recordings are much clearer than what we were able to record in the wild, where we were typically at least half a mile away from the wolves; the signal degrades with distance. As signal quality declines, maximum frequency and end frequency become more useful in individual identification.

Based on our findings and previous research, it is possible to monitor gray wolf populations using non-invasive methods. To do so effectively, researchers would need to record known individuals in a particular area. Once they’ve built up a database of known individuals’ howls, they can conduct nightly surveys. Comparing new recordings to those in the audio library would let them determine which individuals are in an area.

While radio-collaring procedures may still be useful in some cases, vocal identification is a promising alternative for monitoring individuals. Acoustic surveys are still a time-consuming process, but they eliminate the time needed to trap individuals and remove any possibility of accidentally injuring an animal in a trap. Additionally, once researchers gather a database of positively identified individuals, they can use remote monitoring stations to record howls, thus reducing the amount of time spent conducting nightly surveys. Acoustic monitoring could potentially track all the wolves in multiple packs whereas radio-collaring is typically used to track a single member in select packs.

Reposted with permission from our media associate The Conversation.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe