Cleveland skyline. Photo credit: Stefanie Spear

By Susan Cosier

The winds whipping across Lake Erie can average up to 16 miles per hour. And about 7 to 10 miles northwest of Cleveland, there’s a pilot project in the works to capture them. The offshore wind farm would be the second in the nation and the first ever in a Great Lake.

Cleveland, Ohio will be home to America's first-ever offshore wind farm in fresh water: https://t.co/bN3uoMXqoM via @EcoWatch

— NRDC ?? (@NRDC) June 7, 2016

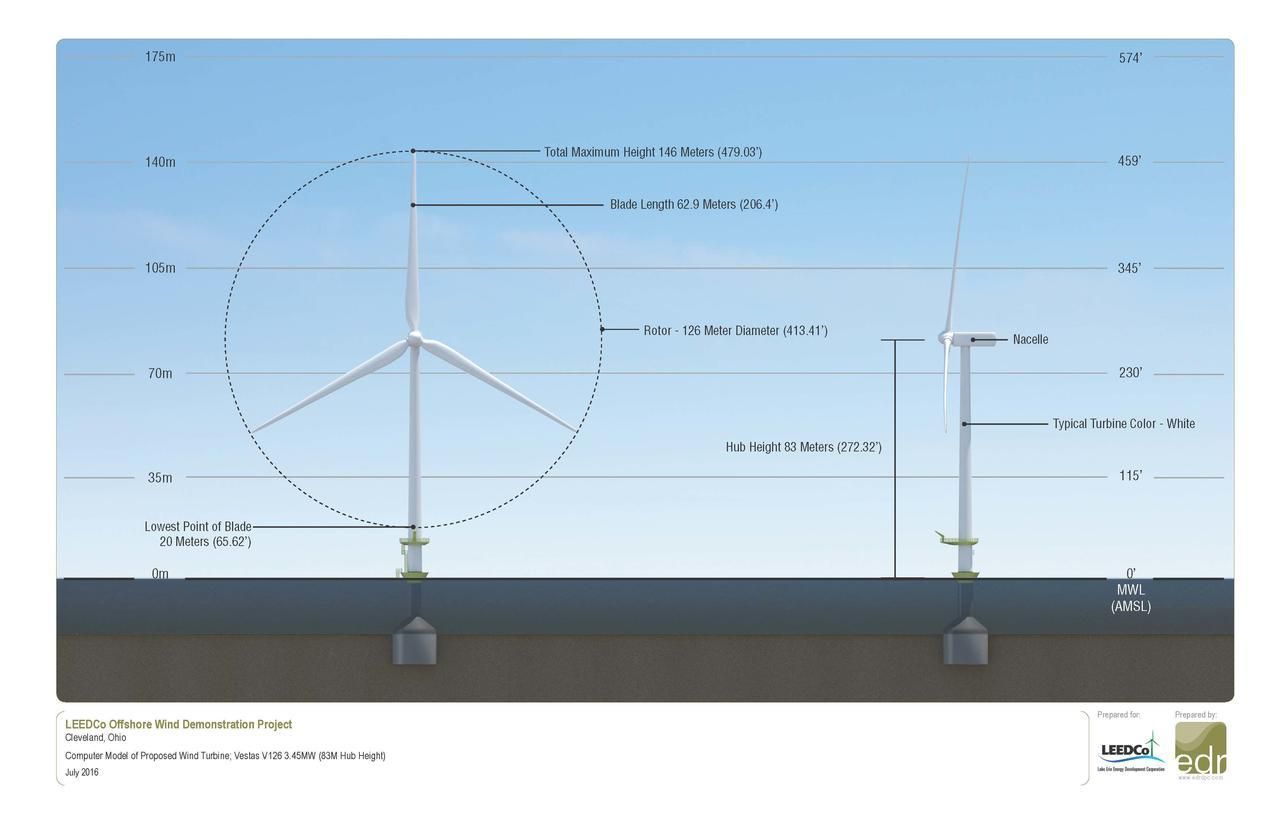

The offshore wind industry is already expanding on the northeastern seaboard, but a freshwater wind farm would face different conditions than those in the salty seas of the Atlantic—the biggest one being ice. Lake Erie, the most shallow of the Great Lakes, usually freezes during winter, so a turbine would have to withstand huge chunks of ice crashing into its pole. That hasn’t stopped LEEDCo, the renewable energy company proposing the project, from pushing ahead. Earlier this month, it submitted its permit application for the project, dubbed Icebreaker Wind.

If the regulatory agencies—including the Ohio Power Siting Board, the state department of natural resources, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the U.S. Coast Guard—give the thumbs up, the towers could go up as early as next year.

Swedish company ReWind Offshore already has 10 turbines twirling in its country’s Lake Vänern. After consulting with ReWind and Eranti Engineering Oy, a Finnish company known for its icebreaking technologies, LEEDCo created its own turbine that can smash through ice. At the water’s surface, a sloped section of the pole will act like the bow of a boat, cutting through any frozen slabs and preventing them from crashing into the turbine.

Icebreaker Wind would generate 20.7 megawatts of electricity, enough to power about 6,000 homes. That’s a relatively small amount, but the farm will also supply lots of valuable info, said Lorry Wagner, LEEdCo’s president. The company plans to study the project closely, ask independent scientists and consultants to collect data on everything from the turbines’ power output to their effect on fish populations, then make the findings publicly available. If successful, the project could attract more wind developers to the Great Lakes. But first, Icebreaker Wind will have to face certain challenges on land.

Representatives from the Ohio-based Black Swamp Bird Observatory and the national American Bird Conservancy have spoken out against wind farms in the Great Lakes, saying the turbines pose a threat to bats and migrating birds. And in a letter to the Ohio Power Siting Board, officials from a number of groups expressed concern about pollution from lubricants and oils used at the turbines, ecological disturbance to birds, bats and fish and restricted access for boaters.

“It comes down to the people, ultimately and if we can’t convince them that this is good for the environment and everything else, then it’s going to be a tough slog,” Wagner said. “We’re making a statement that we are going to clean up the environment and we’re going to do it in a responsible way.”

LEEDCo sent its first proposal to the Ohio Power Siting Board three years ago, but the company pulled its application due to a lack of details on how the farm would be built and how it would work with existing power companies. That was before the U.S. Department of Energy gave the company up to $40 million in Offshore Wind Advanced Technology grants to conduct more research and development.

So far, LeedCo has changed the farm’s location roughly a dozen times to make sure its turbines to have the smallest possible effect on nearby communities and natural resources. WEST, an environmental consulting group hired by the company, also recently assessed the farm’s potential impact on wildlife and found that the six turbines would have minimal impact on local wildlife.

These efforts may help the proposal move through the permitting process, which is the same for land-based projects in Ohio, said Matt Butler, a spokesperson from the Ohio Power Siting Board.

The Ohio legislature mandated in 2014 that wind turbines can’t be within 1,125 feet—measuring from the tip of the turbine’s blade—to the nearest property line, the largest such buffer in the country. Since then, very few wind farms have even gone up in the state. Samantha Williams, a Chicago-based Natural Resources Defense Council attorney, said, in a way, the law is almost forcing wind farms into the lakes.

Ohio created a map that shows the swaths of Lake Erie that might be appropriate for wind farm development in 2008, said Wagner. (Rhode Island has something similar). When wind energy companies start planning, they can request to develop in the most advantageous areas. Still, Butler said the siting board considers each project on a case-by-case basis.

Lake Erie isn’t the only Great Lake wind developers have their eyes on. Two companies previously proposed wind farms off the Canadian shores of Lake Ontario, but the Ontario government has since issued a moratorium on offshore wind development. Lake Michigan could also prove to be a good place for wind energy, said Wagner.

John Scofield, a physicist who researches energy and energy policy at Oberlin College, asks what’s the worst that could happen if the wind farms turn into a mistake? LEEDco just has to take the turbines down.

“The risk is just nothing like some of the risks we have with other energy choices,” said Scofield. For example, coal-fired power plants, like the Bay Shore plant east of Toledo, emit mercury and carbon into the atmosphere and transporting oil can lead to spills almost anywhere, including under the Great Lakes themselves. If an aging pipeline is still allowed to shuttle oil under their waves, certainly offshore wind deserves a fair shot in the lakes, too.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe