Shrimp fishing along the coast of Nayarit, Mexico. Tomas Castelazo / Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

By Paula Ezcurra and Octavio Aburto

Thousands of hydroelectric dams are under construction around the world, mainly in developing countries. These enormous structures are one of the world’s largest sources of renewable energy, but they also cause environmental problems.

Hydropower dams degrade water quality along rivers. Water that flows downstream from the dams is depleted of oxygen, which harms many aquatic animals. The reservoirs above dams are susceptible to harmful algal blooms, and can leach toxic metals such as mercury from submerged soil.

We wanted to know whether dams also impact river systems farther away, at the coastlines where rivers flow into the sea. So we performed a natural experiment comparing four rivers along Mexico’s Pacific coast — two that are dammed and two that remain free-flowing. We found that damming rivers has measurable negative ecologic and economic effects on coastal regions more than 60 miles downstream.

Feeding or Starving Coastlines

We studied four river outflows along the Pacific Coast of Mexico in the states of Sinaloa and Nayarit. Two of these were from the San Pedro and Acaponeta rivers, which are relatively unrestricted, with over 75% of their flow unobstructed.

The other two outflows came from the nearby Santiago and Fuerte rivers, which have over 95% of their flow retained in reservoirs. In addition to restricting water flow, these reservoirs trap sediments — over 1 million tons per year along the two rivers combined.

In unobstructed rivers, sediment flows downstream and is eventually deposited along the coast, helping to stabilize the shoreline and sometimes even to build it up. We found that this was happening along the free-flowing Acaponeta and San Pedro rivers.

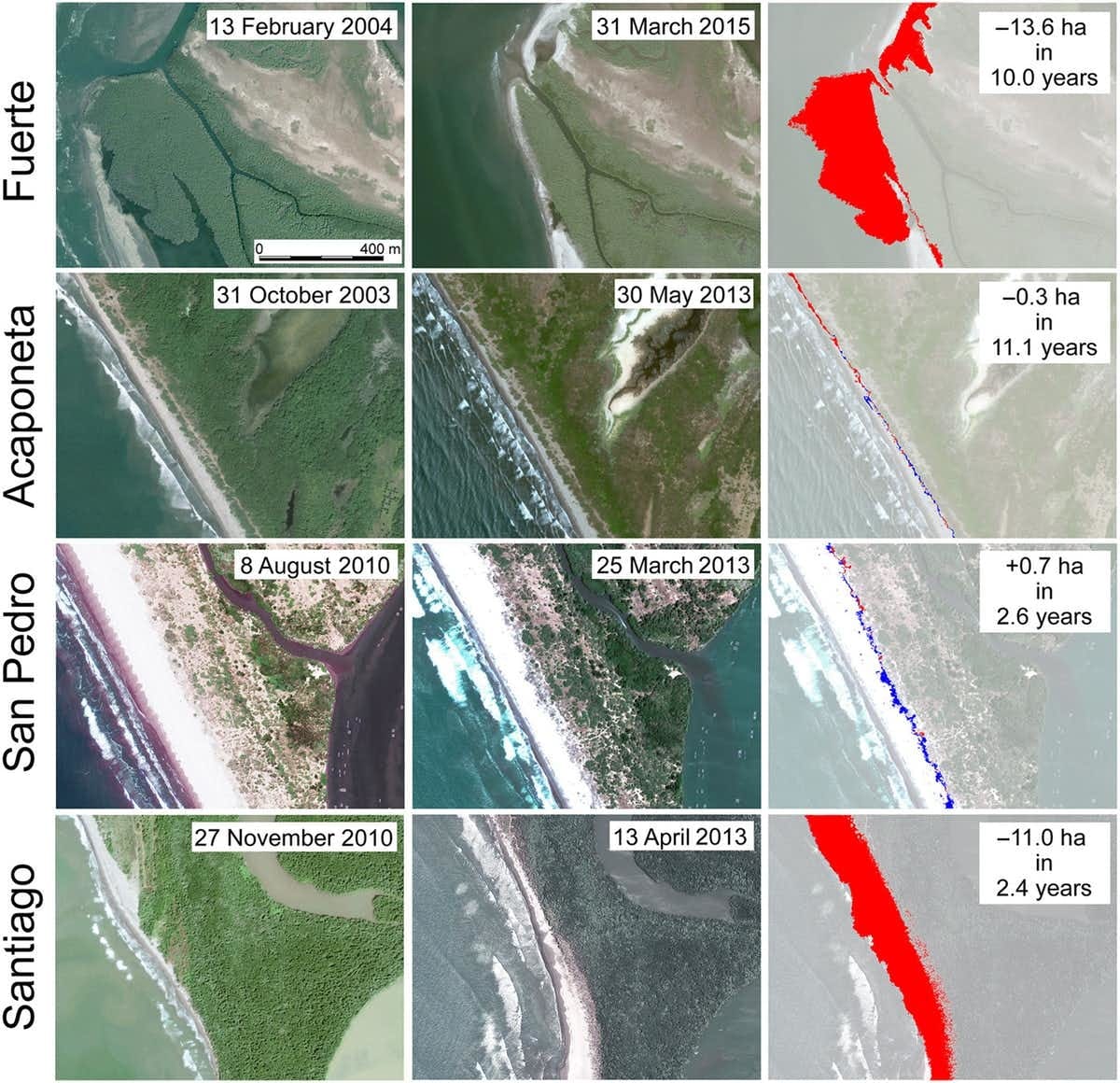

However, because the sediment from the dammed Santiago and Fuerte rivers is no longer carried downstream, wave action takes over at the coast. At the mouths of these two rivers, we found that waves were eroding up to 33 hectares of combined land — equivalent to about 62 football fields — each year, with widespread ecologic and economic effects on the surrounding regions.

The dammed Fuerto and Santiago Rivers show greater erosion where they reach the Pacific coast than the free-flowing San Pedro and Acaponeta rivers. Images at right show coastline changes during the two periods: blue indicates land accretion, red indicates erosion.

Ezcurra et al., 2019., CC BY-NC

The Ecology of Healthy Coasts

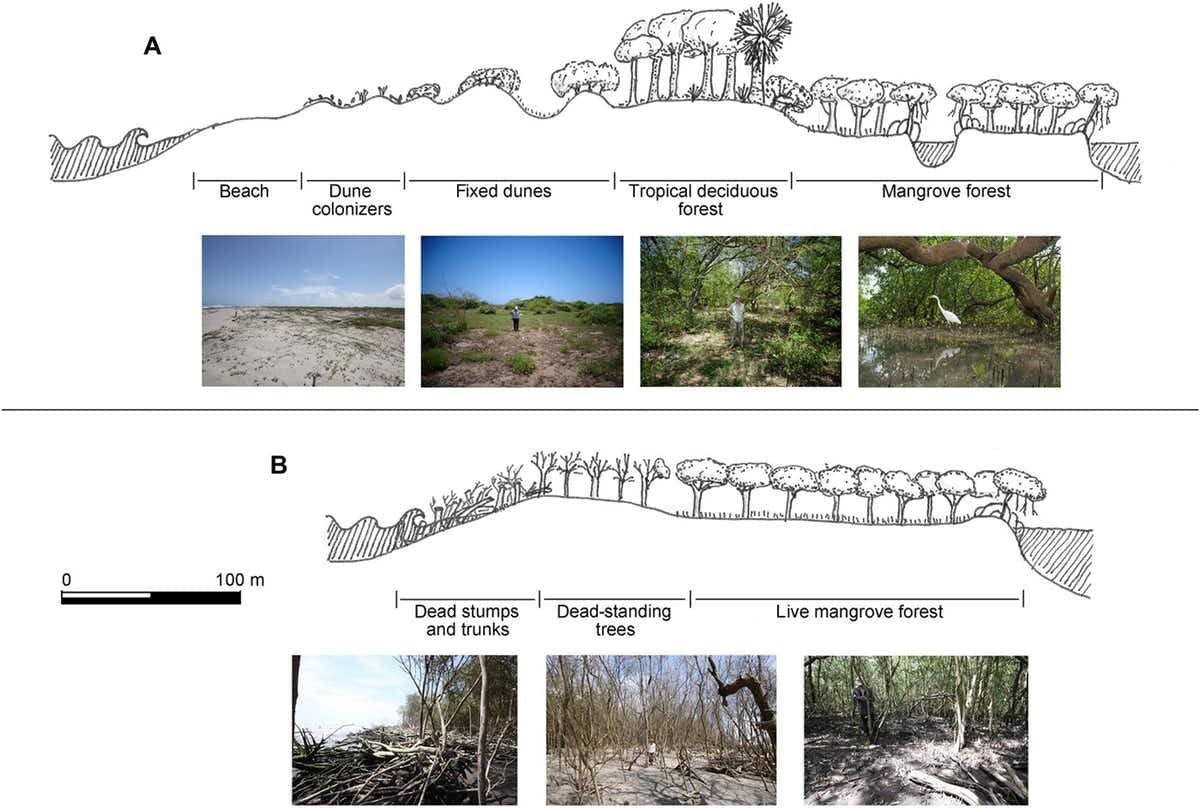

Our field research clearly showed that coastal instability resulting from sediment loss at the mouths of the dammed rivers was harming ecosystems along the shore. For example, we found that coastal regions downstream of free-flowing rivers had significantly more plant diversity. Many of these plants were found only in coastal areas, and therefore had high conservation value.

Coastal erosion due to lack of sediment input from the rivers also reduces critical nursery habitat, such as mangrove forest, where many commercially important fish species spend their juvenile stage. We found that fishing activity at the mouth of the free-flowing San Pedro River was much higher than around the mouth of the dammed Fuerte River. This loss of fishing potential comes at a cost of around .3 million every year.

Reduced sediment flow also deprives coastal estuaries of nutrients. Lucrative shrimp and oyster fisheries in the region we studied rely heavily on nutrient inputs from rivers. In the San Pedro River region, these fisheries generate around .8 million yearly; near the dammed rivers, they have been all but abandoned.

Coastal mangrove wetlands also protect shorelines from hurricanes and tropical storms, and serve as recreational areas and conservation habitat for wildlife. Knowing this, we calculated that the loss of these ecosystem services around the dammed rivers totals .9 million annually.

Vegetation profile of sandbars of the free-flowing San Pedro River (A) and dammed Santiago River (B), where receding black mangrove forest is being eroded away into the advancing coastline

Ezcurra et al., 2019, CC BY-NC

Still another valuable function that mangrove wetlands perform is storing “blue carbon” in plant tissue and soils, reducing the effects of climate change. But when coastlines recede and mangroves are destroyed, this carbon is released. We calculated that mangrove loss in our study region represented a loss of around 0,000 in annual carbon trading potential for this region.

Adding up all of the ecological services that coastal ecosystems provide, we estimate that the economic consequences of shoreline loss around the Santiago and Fuerte rivers related to hydroelectric damming totaled well over million yearly.

Letting More Sediment Flow

Because sediments are so essential to areas around river mouths, reducing sediment trapping behind dams could mitigate some harmful impacts on coastal areas. There are several ways to do this — notably, sediment bypassing, or diverting a portion of the sediments flowing from upriver around dams and allowing it to rejoin the river downstream.

This strategy can be included in new construction or incorporated into existing dams. In addition to reducing dams’ environmental impacts, it also increases dams’ service lives by reducing the rate at which their reservoirs fill up with silt.

To date, environmental impact assessments of large inland dams have often failed to properly analyze the impacts that these dams will have downriver on coastlines, estuaries, deltas and lagoons. Our study shows how important it is to fully account for dams’ environmental and economic impacts along coasts and basins.

Mexico may be at a juncture in its approach to hydropower. The Mexican government recently contracted with Hydro-Quebec, the world’s largest hydroelectric power producer, to revamp existing dams across the country. And a recent study by a Mexican nongovernment organization, SuMar-Voces por la Naturaleza, reported that a long-disputed proposal to build a new hydroelectric dam at Las Cruces is neither financially feasible nor needed to meet energy demand for the region, prompting national groups to call for the final cancellation of the project.

We believe that Mexico and all nations working to develop efficient, low-impact energy sources should take a holistic approach to future dam-related projects, so they can weigh their potentially harmful consequences. The coastal effects that we documented should be part of those reviews.

Paula Ezcurra is a digital communications specialist with the Gulf of California Marine Program, University of California San Diego.

Octavio Aburto is an assistant professor of marine biology with the the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, University of California San Diego.

Disclosure statement: Octavio Aburto receives funding from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, UC MEXUS and the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust. Paula Ezcurra does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond her academic appointment.

Reposted with permission from our media associate The Conversation.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe