Hurricane Florence on Sept. 12, 2018. ESA / A.Gerst, CC BY-SA 2.0

By Astrid Caldas

On May 21, the first named storm of 2019, Andrea, was recorded on the north Atlantic. This makes 2019 the fifth consecutive year that a named storm has formed before the official start of Atlantic hurricane season.

Something caught my eye when I read that: the number five. That’s because, according to NASA, 2018 was the fourth warmest year in a continued warming trend since record keeping began in the 1880’s, with temperatures 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit (0.83 degrees Celsius) warmer than the 1951 to 1980 mean. And with it, a string of five consecutive years have been recorded as the five warmest on record. I will say this again: the last five years have been the five warmest years on record.

Is climate change having an effect on hurricane season, or on hurricanes themselves? Hurricane season starts on June 1st. Let’s take a look at the latest forecasts and science.

Hurricane Forecasts and Their Messages

On April 16, Colorado State University (CSU) released its hurricane outlook for the 2019 season, forecasting 13 named storms with 5 of them turning into hurricanes, of which 2 would classify as major (categories 3 and above).

On May 23, the National Hurricane Center, part of the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration (NOAA) released their forecast, predicting a “near-normal” season with 9 to 15 named storms and 4 to 8 hurricanes, with 2 to 4 being major ones. An average season has 12 named storms, six hurricanes and three major hurricanes. The numbers are very similar to the ones from CSU.

The odds for that near-normal season are 40%. Odds for above-normal or below-normal activity are both at 30%. But, as I mentioned last year, odds are not certain predictions. They are just that: odds (see below for more on that). And the last couple of years certainly reminded us of that.

Years to Remember – in More Than One Way

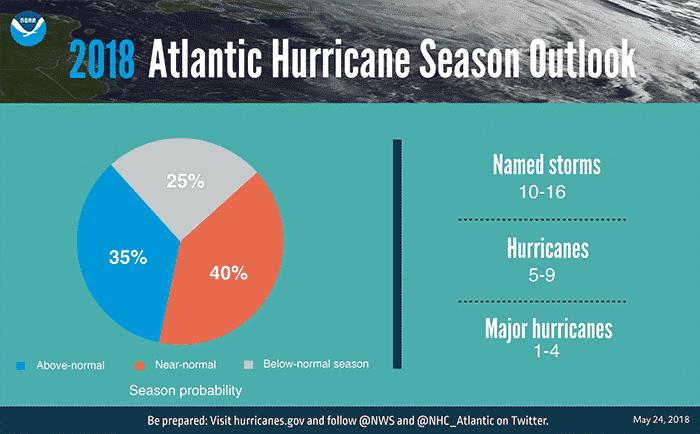

NOAA’s forecast for the 2018 season also had a near-normal probability of 40%, with 35% odds of it being above normal, and 25% odds of being below-normal. It forecast 10 to 16 named storms and 5 to 9 hurricanes, with 1 to 4 being major. What we saw was a season tilted toward the higher side of the predictions — there were 15 named storms and eight hurricanes. Two of those were major, and two hurricanes — Michael and Florence, the latter not a major hurricane but a category 1 — caused roughly billion in estimated damage.

While the probabilistic predictions may not have raised any eyebrows, when a record four hurricanes were active at the same time, that caught my eye.

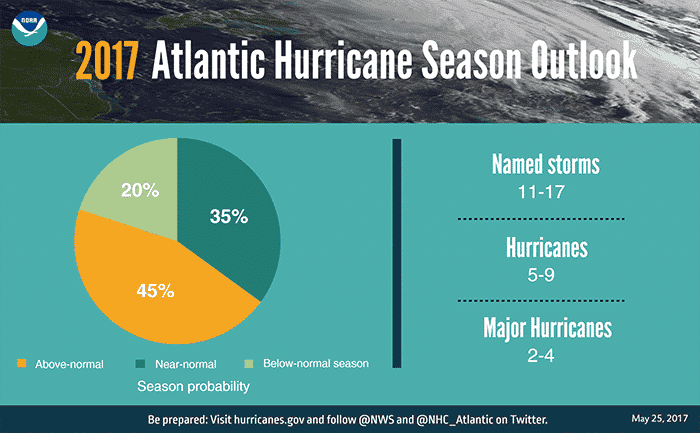

If we look further back, at 2017, the probability of an above-normal season was at 45%, and below-normal activity was at 20%. The forecast called for 5 to 9 hurricanes, with 2 to 5 being major — and the reality blew the predictions: we had 10 hurricanes with 6 major ones. Three of these major ones hit the U.S., and nobody will forget the string of names Harvey, Irma and Maria anytime soon. That also caught my eye.

However, I was not surprised when the numbers fell outside of the given range.

Understanding the Forecast

That is because the range in numbers given in NOAA’s forecast has a 70% probability, meaning that “The seasonal activity is expected to fall within these ranges in 7 out of 10 seasons with similar climate conditions and uncertainties to those expected this year. They do not represent the total possible ranges of activity seen in past similar years.” So, there you have it, in plain language, that the actual numbers for 2019 (as in any season) may be different from the ones in the forecast.

What Do These Seasons Tell Us?

Forecasts are based on probabilities calculated from conditions at the time of the forecast, and as such, there is ample room for conditions to change and actual facts to fall outside the probabilistic calculations, as the numbers for 2017 show. At the time of the 2018 forecast, sea surface temperatures were running below average in the area where tropical storms form, and the forecast was based on those conditions. For this year, NOAA stated that there are competing signals affecting the forecast: an ongoing weak El Niño is expected to suppress intensity of Atlantic hurricane activity, while warmer-than-average surface waters and an enhanced African monsoon are forces that could lead to increased activity. Will these conditions change and affect hurricane activity? Probably. That is also why NOAA releases an updated forecast later in the season, usually in early August. Mind you, the updated forecast is based on the same probabilistic calculations, only using updated conditions.

Most importantly, it only takes one hurricane to hit to cause possible devastation. Nobody can tell ahead of time how many hurricanes in a season will strike land. One should always remember that, and be prepared, such as by following the NOAA/NWS storm tracking page and FEMA hurricane preparation guidance. And with the last couple of seasons seeing major hurricanes (some making landfall), preparedness takes on a new urgency.

But are we really seeing more of these major hurricanes, or is it just an impression — or coincidence?

Hurricanes Are Getting Stronger

The fact is that global warming is loading the dice when it comes to hurricane strength, with abnormally warm water being one of the culprits because it has the potential to increase hurricane power. Two of the most powerful hurricanes in recent history, Harvey and Florence, gained immense strength in very little time, and one of the reasons was that the sea surface temperature of the water in its path was running well above normal. In the case of Harvey, Gulf waters were warmer than any time on record, and temperatures along Florence’s path were 3.6°F (2°C) hotter than normal. That warmer water is linked to human-caused warming due to emissions from burning coal, oil and gas. And it is worth noting that, after further analysis, hurricane Michael was upgraded to a category 5 in April 2019, months after it hit in 2018.

But it is not just the wind and strength of a hurricane that are amplified by climate change: global warming can also increase the amount of rain that hurricanes bring. Warmer air holds more moisture (read: more water to fall when it rains), and global average temperature is currently about 1.8°F (1°C) warmer than it was in the late 1800s. In fact, a study found that the record rainfall from Harvey was roughly three times more likely and 15% more intense than in a world without global warming. Another study found that higher ocean heat content and sea surface temperatures make hurricanes such as Harvey “more intense, bigger, and longer lasting and greatly increase their flooding rains.”

Furthermore, research suggests that there has been an increase in intense hurricane activity over the past 40 years, and since the mid-1970s the number of strong hurricanes reaching categories 3 and above has roughly doubled.

So, while we wait for this hurricane season to develop, let’s be mindful of probabilities, a changing climate, changing conditions, and most of all, preparedness. It reduces risks, helps ensure communities withstand the next storm, and can save lives.

Astrid Caldas is a climate scientist with the Climate & Energy program at the Union of Concerned Scientists.

- How Rural Areas Like Florida's Panhandle Can Become More ...

- Early Forecasts Suggest 'Quiet' 2019 Hurricane Season - EcoWatch

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe