As if the fact that, in the U.S., we waste 40 percent of our food isn’t shocking enough, a recent study by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences finds that total emissions of the potent greenhouse gas methane are almost twice as high in the U.S. as previously thought. More potent than carbon dioxide, methane is a deadly contributor to global warming.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), all that uneaten food accounts for 23 percent of methane emissions as it rots in landfills. Other sources include livestock operations and oil production. And yet, properly captured or, better yet, generated in anaerobic digesters that break down food waste before it ever reaches landfills, methane represents a cleaner energy source for use in heating homes, running engines, and generating electricity. Yet challenges to the widespread availability and use of biogas remain.

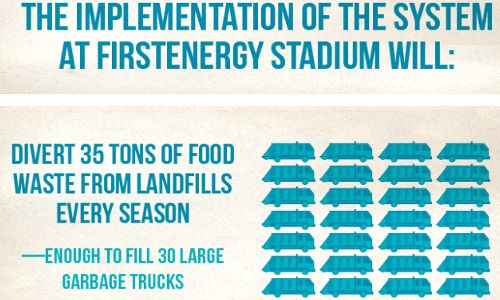

Enter FirstEnergy Stadium in Cleveland, where a new partnership with the Cleveland Browns and the Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy has implemented a new system to will divert an estimated 35 tons of stadium food waste from landfills into biodigesters for conversion into energy. The system, called Grind2Energy, is a technology from Emerson’s InSinkErator, a brand many associate with in-sink disposals found in kitchens across the U.S. Far more than an industrial-strength garbage disposal, it’s an integrated system that includes leasing, installation, and service coverage of a closed system that grinds up food waste into a slurry and transports it to an anaerobic digestion facility where it is converted to energy.

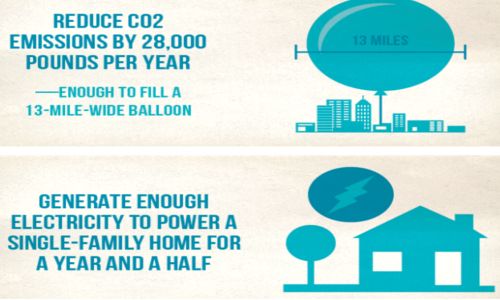

Slurry from FirstEnergy Stadium travels to an anaerobic digester operated by Quasar Energy group at the Ohio State University’s Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center where it will generate enough electricity for a single family for a full year, produce enough natural gas to heat 32 homes for a month and recover enough nutrients to fertilize three football fields of crops.

As well as diverting food waste from landfills, the system at FirstEnergy Stadium will reduce carbon emissions by 28,000 pounds per year, generate enough electricity for a single family for a full year, produce enough natural gas to heat 32 homes for a month, and recover enough nutrients to fertilize three football fields of crops.

The closed nature of the system eliminates odors and enhances kitchen hygiene, decreasing reliance on cleaners and pesticides. The setup creates savings in waste removal because storage tanks can compactly hold three to four weeks of organic slurry. In some cases where such systems are in place, facilities have the opportunity to buy renewable energy and biogas back from anaerobic digester facilities.

The project’s partners hope that the systems’ implementation in a sports arena will fuel public awareness, in keeping with the U.S. Deparent of Agriculture (USDA) and EPA’s U.S. Food Waste Challenge, and encourage producers, manufacturers, communities, and government agencies to reduce and recycle food waste. According to David Krems, Business Development Manager for Grind2Energy, the system’s implementation in Cleveland has generated a lot of interest.

“We have the NFL asking us how do we do this at every NFL stadium,” Krems said.

Currently the company has three Grind2Energy systems operational in Ohio, and one deploying in Milwaukee. They’re working to meet high demand for the system in the coming year, especially in the Northeast where many biodigesters are being built, making Grind2Energy a priority for global conglomerate and green housing innovator Emerson. Emerson is satisfying an existing demand. According to Sustainable America’s March 2013 survey, U.S. consumers support “stronger efforts to reduce food waste in restaurants and grocery stores”. And yet the survey found that the perceived importance of these issues lagged behind others—jobs and the economy, for example.

While a food-waste-to-fuel system doesn’t prevent food waste, according to Dana Gunders, a staff scientist with the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), which partnered with the Green Sports Alliance to promote sustainable practices in the sports world, “It’s a great way to reach people who are often difficult to reach through typical environmental channels . . . I think it’s one more block in the domino effect that will eventually lead to change.”

While the widespread integration of anaerobic digesters into the energy grid continues to face hurdles like viable partnerships with energy providers and high initial capital costs for building facilities, they have already proven their value in use by the dairy industry in all 50 states, according to Tom Gallagher, CEO of the Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy. And hopefully the model at FirstEnergy Stadium will be replicated at stadiums, arenas, and other large venues with high levels of food waste across the country.

As director of the NRDC Sports Greening Project and Sustainable America board member Dr. Allen Hershkowitz puts it: “Anaerobic digestion is an important technology that provides great potential to manage our food waste in a more ecologically intelligent way.”

While turning wasted food into energy ranks low on the EPA’s food waste recovery hierarchy, its combined benefits, including the mitigation of greenhouse gas generation, are undeniable. As support for bans on sending food waste to landfills grows, the true potential of anaerobic digestion, through the widespread implementation of systems like Grind2Energy, will become clear.

Turning food waste into renewable energy will become increasingly profitable as relationships between biogas producers and energy providers develop. If we can turn food waste into fuel, we’d go a long way toward reducing some of the harmful linkages between the food and fuel markets in the U.S.

Visit EcoWatch’s SUSTAINABLE BUSINESS page for more related news on this topic.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe