Houston’s Tall Buildings and Concrete Sprawl Made Harvey’s Rain and Flooding Worse

The science is clear that in order to prevent more extreme weather events like hurricanes, we need to stop burning fossil fuels. Thursday, EcoWatch reported on a study that found major hurricanes in the past decade were made five to 10 percent wetter because of global warming, and another study last year calculated that the record rainfall that flooded Texas during Hurricane Harvey was made three times more likely due to climate change.

Now, a second study focusing on Hurricane Harvey that was published in Nature Wednesday pointed to another thing we can do to reduce the impact of these devastating storms: change the way we build cities.

Researchers at the University of Princeton and the University of Iowa used computer models and historical data to determine that urbanization in Houston made both the flooding and the record rainfall worse than it would have been in a rural area, a Princeton press release explained.

New article published in the journal Nature by IIHR researchers and colleagues from@PrincetonU linking urban sprawl to increased intensity in flooding resulting from Hurricane Harvey in Texas https://t.co/lRlZQzfgrL @uiowa @UIowaEngr pic.twitter.com/meAIQ9LwgG

— IIHR (@IIHRUIowa) November 14, 2018

While this can help Houston make changes going forward, it also has major implications for other Southeast and Gulf cities facing the threat of wetter storms.

“Hurricane Harvey’s impacts on Houston highlight hazards to coastal cities along the Gulf Coast and Eastern Seaboard of the United States,” co-author and Princeton civil and environmental engineering professor James Smith said in the press release. “An unfortunate repeat performance from Hurricane Florence this year underscores the problems of extreme tropical cyclone rainfall in urban settings.”

Houston has both grown up and out in recent years, and both of those had an impact on rainfall and flood risk. But how does that work exactly?

Flooding

Urbanization’s impact on flooding is pretty common sense. More concrete streets and sidewalks means less water can be absorbed into the ground, leaving it to flood those streets instead.

Researchers compared yearly flood peaks with population growth, and also compared the contemporary results with flood peaks from the 1950s, when Houston was much less built up. Sure enough, as development increased, so did flood risk.

“Urbanization is generally associated with a significant reduction in storm-water infiltration,” Director of Iowa’s Hydroscience and Engineering research center (IIHR) Gabriele Villarini explained in the press release. “Houston has experienced one of the most impressive urban-development booms in U.S. history, and with growth comes an increase in impervious surfaces. This increase in urbanization, combined with the region’s flat clay terrain, represents a very problematic mix, even with flood-mitigation measures in place.”

Rainfall

The reason that urbanization increases rainfall is a little more complicated. Basically, the increased number and height of buildings creates something called “surface roughness” that increases friction and, therefore, rainfall when the storm winds blow over it.

“When Hurricane Harvey blew into Houston, it literally got snagged on the city’s tall skyscrapers and towers,” Villarini said. “The friction caused by high winds buffeting tall buildings created a drag effect that influenced air and heat movement and resulted in optimal conditions for precipitation.”

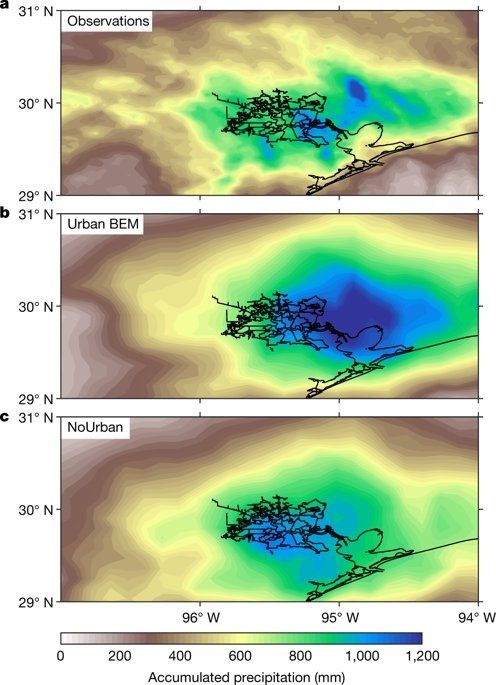

Researchers used computer models to run the same storm over the same geographic area with Houston’s current infrastructure and with open fields. They found that less rain fell and that rainfall patterns changed in the imaginary rural Houston, as this graphic shows.

Rainfall from Harvey in urban v. rural Houston@3rdrockhome

Now that the researchers have shown the impact current urban design has on storms, they hope that urban planners will use that information to reduce risk.

“For every new roadway poured and for every new high-rise erected, there is an increased risk for more adverse rainfall and flooding, and that’s certainly something that city officials and residents should consider when they contemplate future growth,” Villarini concluded.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe