Hazelnuts. George Hodan, CC0 Public Domain

By Sarah Derouin

Drive along the backroads of the U.S. Midwest and you’ll see farm fields stretching for thousands of acres. The rolling hills are sliced into straight rows, filled with the same plants all standing in line.

Many farmers here are monoculture-focused, planting only corn or soybeans. These crops are annual plants; each year, fields are prepared and planted, using large amounts of energy, fertilizers, and pesticides. Excess agrochemicals seep from field to stream, polluting waterways and killing beneficial insects, while constant plowing hastens soil erosion. In years of excess water, like the 2019 flooding, these detrimental effects can be exacerbated.

But what if many of these problems, ecologic and economic, could be tempered by going back to the Midwest’s roots? Instead of one or two dominant crops being grown, could some farmland be planted with perennial, native, nut or fruit trees?

Trees stabilize soils while holding and filtering water, encourage biodiversity, which can reduce the need for fertilizers and pesticides, and temper the effects of a changing climate. And the nuts and fruits can be harvested and sold, diversifying a farmer’s crops and revenue streams.

Changing course from monocropping to diverse multicrop farms has a few bottlenecks, but researchers are working to help farmers with agroforestry — as the combination of woody perennials like trees and shrubs with annual crops is known — and propping up nut tree markets. If successful, agroforestry could be a boon to Midwestern farmers and communities.

Alley cropping like this co-planting of soybeans between rows of walnut trees allows farmers to diversify their crops, while reaping the benefits of perennial plants (water storage, soil erosion prevention, shade and wind breaking, among others). NAC / CC BY 2.0

Annual Planting, Annual Challenges

Row cropping is king in the Midwest, covering three-quarters of all the land. Corn and soybeans blanket most fields, and producing these singular species gobbles up energy: around the world, agriculture is responsible for a large chunk of human-caused emissions (10-12% of CO2, and a whopping 54% of other non-CO2 greenhouse gases).

Annual tilling of fields reveals bare earth leading to erosion of the soil — a little or a lot at a time. Over the past century, some researchers estimate that a third of the most fertile topsoil has disappeared from the Midwest.

Relying on a single crop also means that it only takes one weather event — a drought, late freeze, or flooding — to devastate a harvest. In 2019, the Midwest experienced an extremely wet spring, causing more than 7.9 million hectares (19.4 million acres) of corn to not be planted. Considering our changing climate, farmers who practice monocrop farming may therefore face more economic uncertainties as unexpected weather becomes the norm.

“In any one year, crops can be majorly impacted by the environmental situation,” said Sarah Lovell, director of the Center for Agroforestry at the University of Missouri. “Whereas if we have a wider range of crops, they’re oftentimes more resilient under those conditions.”

“In the upper Midwest, we have a water quality problem,” said Jason Fischbach, woody crops specialist at the University of Wisconsin Extension and co-leader of the Upper Midwest Hazelnut Development Initiative (UMHDI), adding that tillage and annual row crops are to blame. He said that with climate change, larger storm events are making things worse. “We’ve seen two 500-year floods in the last five years in our neck of the woods. And farther south, where there’s more exposed soil, it is just getting worse and worse.”

Bill Davison, program manager of tree crop commercialization at Wisconsin-based agroforestry research nonprofit the Savanna Institute, said that if farmers could establish perennial vegetation, many environmental issues could be mitigated. Trees and shrubs reduce runoff and erosion, can foster less agrochemical use, and encourage the capture and storage of water, while filtering agrochemicals. Davison said replacing annual crops with nut and fruit trees “takes a system that is burning carbon, and is based on fossil fuel inputs, and replaces it with a more sustainable form of production.”

In fact, Midwestern farms might be the perfect spot for sequestering carbon while making a profit. In a new book, It’s Not Too Late, Frances M. Lappe writes that gradually expanding alley cropping — where widely spaced rows of trees are planted with crops like corn in between — could remove large amounts of carbon from the atmosphere: hitting a target size of 20 million hectares (50 million acres) could remove 1.07 gigatons of carbon dioxide from the air.

While all these benefits seem straightforward on paper, there is still a big factor for farmers: what will it cost? “This is the challenge: it does reduce soil and nutrient loss, but does it really help the farmers’ bottom line?” said Fischbach. He noted that for farmers to fully embrace planting perennials, agroforestry solutions need to be “productive conservation.”

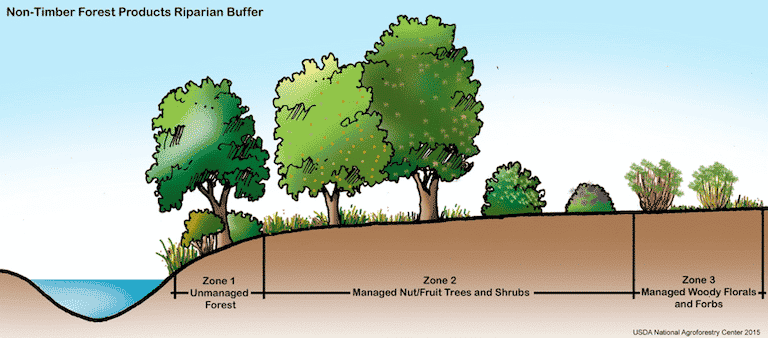

Riparian agroforestry adds fruit or nut trees near water sources to improve water quality, wildlife and pollinator habitat, and increase revenue sources. NAC / CC BY 2.0

Making Agroforestry Work in the Midwest

For farmers interested in stepping away from monoculture farming, planning new agroforestry plantings can feel overwhelming, so researchers at the USDA’s National Agroforestry Center (NAC) are trying to provide information tailored to farmers’ needs.

“It’s really practice-specific and farmer-specific,” said Matt Smith, a research ecologist with the NAC, noting that farmers are trying to address problems on their land with potential agroforestry solutions — and it’s not always a one-size-fits-all solution. “What one farmer is doing, their neighbor could be doing something completely different,” he said, adding that agroforestry solutions could be geared toward ecological or economic goals.

Agroforestry practices have to yield specific solutions to be embraced. For example, on big monoculture farms, alley cropping might not work. “[Farmers] have huge fields where they’re planting 24 rows at a time,” said Missouri’s Lovell. “Jockeying around trees just really isn’t feasible for farmers.”

Instead, farmers could take a bolder approach and change larger areas into perennial crops. Lovell explained that some “difficult” areas — the small, odd-shaped fields, flood-prone areas, or hillside fields — can be perfect for perennial crops. For example, for a sloped, flood-prone field, she noted that crops like pecan are well adapted to that type of setting. The change could be more profitable in the long run, and have environmental benefits for the farmer.

“Replacing annual crops with perennial crops generally improves the quality of habitat for wildlife and in many cases will lead to increased populations of species that depend on perennial cover,” said Davison. He added that by increasing the size of riparian buffers and windbreaks, wildlife will have more natural habitat. More diverse, robust wildlife also means more habitat for pollinators and beneficial insects in general. “This can lead to a more balanced system that has fewer pest and disease outbreaks,” Davison said, adding this ultimately leads to lower costs of production for farmers.

Gary Bentrup, a research landscape planner at NAC, said farmers turn to agroforestry not only to solve problems on their land, but to also even out their labor demands. “You can have some really peak times, particularly if you just have one or two crops,” said Bentrup, adding that for a diversified farm, labor demand is spread out over the whole year.

Bentrup said there’s a lot of interest in agroforestry among farmers. “[They’re] looking at integrating livestock, which can create a more closed loop system with animals providing fertilizer, and in some cases providing management services such as weed and pest control,” said Bentrup. “These systems can also enhance livestock well-being, and shade [and] protection from extreme weather events that we’re seeing more frequently.”

Windbreaks between fields introduce perennial plants to a system, while adding soil erosion protection and water capture and filtration. Farmers can plant trees or shrubs that produce fruits or nuts, or after a few decades, they can harvest the trees for wood. NAC / CC BY 2.0

But some farmers are hesitant to embrace agroforestry practices. Transitioning toward a diversified crop system means a significant outlay. “They have a significant investment in their current operation: investment in equipment, in how their farm operation is laid out, in the buildings and facilities,” said Rich Straight, a forester at the NAC. There are big financial considerations when farmers transition to a different type of scale of farming.

There’s also a steep learning curve. “If a person spends half of their adult life farming in one particular way, it’s a big investment in time and learning and finding resources,” said Straight. “There’s a fair amount of momentum going one direction. And change, as we all know, is not easy.”

Related to this, there is a social and emotional component of transitioning to agroforestry that should be respected. “Folks say, ‘It breaks our heart to plant trees, because our parents and our grandparents spent decades removing the trees from the landscape,'” said Straight.

Changing farming techniques can not only cause familial stress, but community tension as well. “I’ve talked to farmers who have transitioned to organic farming out here in Nebraska, and they have found that it caused a breakdown in relationships with other farmers in the area, that they maybe have known their entire life,” said Straight. “People now perceive you as somewhat of an outsider, or they are thinking you’re judging them because you’ve changed to a new system.”

The trio at NAC noted that education for lenders, farmers and communities can help with resistance to agroforestry. “The National Agroforestry Center is always trying to consider the barriers and we do this by talking to landowners and natural resource professionals,” said Smith, adding that they post potential solutions and latest research on their website. There are also investors who are increasingly looking to help farmers transition to agroforestry.

Farmers who have made the switch have also formed an effective support system. “It’s a very supportive community of people who are looking at growing food and working the land in a different fashion,” said Straight. “It can be very encouraging in that way [and] people do seem to rally around each other and support and encourage and share information.”

Hazelnut alley cropping, where the nuts grow between an annual crop’s rows. Savanna Institute

Is the Answer Nuts?

“For a long time, we would just wag our finger at farmers and say you’re doing bad things — do something different,” said Fischbach, but he added that suitable solutions were murky. So over the last couple of decades, the research community has focused on the feasibility of perennial crops, especially in the Upper Midwest where Fischbach works. “I was brought on to try to help revitalize the agricultural economy,” he said, adding that the short growing season and “crappy, clay soils” make farming a challenge there.

So he and his team looked to native trees for an answer: enter the hazelnut. The team began looking at hazelnuts in part because they are a nearly billion a year market, a big number that’s predicted to grow.

While the majority of them are grown in Turkey, some recent weather events mean the country cannot keep up with demand. Currently, all of the U.S.-grown hazelnuts come from orchards in the Willamette Valley of Oregon, generating 0 million in annual revenue, so the Midwest may be in a great position to cash in on a growing market.

There are two main varieties of hazelnuts: European and American. European nuts are bigger, and a popular snack there: “People eat them like we eat peanuts,” said Fischbach. The American hazelnut is more of a shrub and produces smaller nuts, but the plants are prolific. “The American hazelnut is widely distributed across the upper Midwest and actually most of the eastern U.S.,” he said.

Nut size isn’t necessarily an issue, as the American hazelnut can be used as an oilseed crop. “The nuts are 60% oil by weight and the fatty acid profile is identical to olive oil,” said Fischbach, adding that it can be called “the northern olive oil.”

For the past 14 years, scientists have been working on breeding a hybrid of the European and American varieties; they’re aiming for a hardy shrub that can tolerate a variable climate, yet produces bigger nuts suitable for snacking on. Fischbach said that although they created a plant that grows well from seed, breeders are still trying to crack the code on propagating, or cloning, the most successful plants.

While hazelnuts may be the nut of the future for the Midwest (see Savanna Institute’s report “What will it take to catalyze the Midwest hazelnut industry?” here), they aren’t the only perennial plant that can help farmers diversify. Davison said that on some of the demonstration farms affiliated with them, farmers are combining multiple perennial crops.

“A system that is working for farmers would be chestnut trees, Christmas trees, and blueberries,” said Davison. He explained that these crops need similar types of soil and conditions, so they work well together. And at the end of the day, Davison said having three crops is “a really good economic scenario for the farmers.”

“We kind of overlook the huge potential of a lot of species that are native to the Midwest,” said Lovell. There are many other native species — black walnut, pecan, elderberry, aronia, pawpaw, persimmon — that we haven’t fully incorporated into our food system.

“They’re oftentimes much more resilient and adapted under more extreme climate conditions,” Lovell said. “Looking into the future, there’s just a lot of potential here.”

Chestnuts can also grow well in alley cropping systems. Savanna Institute

Reaping the Rows

When agroforestry is initially embraced, it’s often for smaller efforts like windbreaks. These narrow bands are often fast-growing trees like poplar or pine that become profitable about 30 years later, but only for a one-time sale. If a farmer plants hazelnuts for that windbreak, though, Fischbach said that they will create a positive cash flow in just five or six years.

“That’s how we’re trying to position hazelnuts,” said Fischbach. “We’re not trying to convince people to take the other 40 acres of corn and beans and put in hazelnuts; we want you to deploy these hazelnuts in a way that makes your whole system better.”

Davison has also noted this approach and said he’s seeing signs of more people changing the way they farm. “When I talk to some nursery owners, for the first time in 40 years, they have been overwhelmed with orders for trees — more than they can meet. It’s pretty exciting.”

Once the hazelnuts ripen, the next questions are around harvesting and processing, and since farmers who only grow a few rows of hazelnuts might not want to invest in their own harvesting equipment, UMHDI created Grower Networks in 2019 to help farmers pool resources for harvesting, processing and selling them. Fischbach said that early on, Midwest farmers would pick hazelnuts by hand, but that quickly became untenable.

So they tried a blueberry picker, and Fischbach said they work pretty well, especially considering that they were “built to handle soft, squishy, wimpy little blueberries.” He said they are still tinkering with the machine for greater efficiency. And because the Midwest is new to the nut industry, with no processing plants operating nearby, UMHDI created a processing incubator in Ashland, Wisconsin, so growers can now ship to this regional plant to crack and separate hazelnut kernels from their shells, to avoid large shipping costs for processing in the Northwest.

Researchers from the Savanna Institute use their hazelnut harvester on a farm in Wisconsin. Savanna Institute

The Future of Farms?

Shedding the image of a corn- and soybean-only farm might seem far-fetched, but Lovell said the Midwest has the potential to grow much more. “There’s so many things that we can be producing on this landscape that would just be a win-win-win in terms of the environmental health, the human health, [and] other cultural aspects,” she said.

Increasing perennial crops and reducing monocropping has far-reaching benefits for the ecosystem, she added, like that potential gigaton of carbon sequestration. “All of that plant material that you see above ground, and then oftentimes [in] equal amounts below ground, is carbon that’s being stored.”

“It’s just such an exciting time in agriculture,” said Fischbach. “We really have some new tools, new energies, new young people doing the hard work of developing new systems.” He added that while farmers are willing to try new agroforestry crops like hazelnuts, it still relies on Midwestern markets and companies like the American Hazelnut Company, a small-scale operation that processes and sells Midwest-grown hazelnut products like oil, hazelnut flour and snackable kernels.

“Ultimately, for any of this to work, we need consumers in the Midwest to eat hazelnuts,” he said, adding that convincing folks to buy the little nut isn’t too difficult “because it tastes great.”

So Midwesterners can be on the lookout for this tasty product that supports area farmers. And if hazelnuts take off, one day a locally grown Nutella knockoff might even be pantry staple.

This report is part of Mongabay’s ongoing coverage of trends in global agroforestry. View the full series here.

Reposted with permission from Mongabay.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe