Every year the Gulf of Mexico hosts a human caused “dead zone.” This year, it will approach record levels scientists from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration — or NOAA — estimate, in a statement released Monday.

The researchers predict the hypoxic zone — an area with little to no oxygen that can kill marine life — to be nearly 8,000 square miles or roughly the size of Massachusetts.

NOAA wasn’t the only organization to estimate a near record dead zone this summer. Researchers from Louisiana State University (LSU) released a statement on Monday predicting this year’s dead zone to be 8,717 square miles, making it the second largest on record.

“We think this will be the second-largest, but it could very well go over that,” said Nancy Rabalais, a marine ecologist who studies dead zones co-authored the LSU report, as CNN reported.

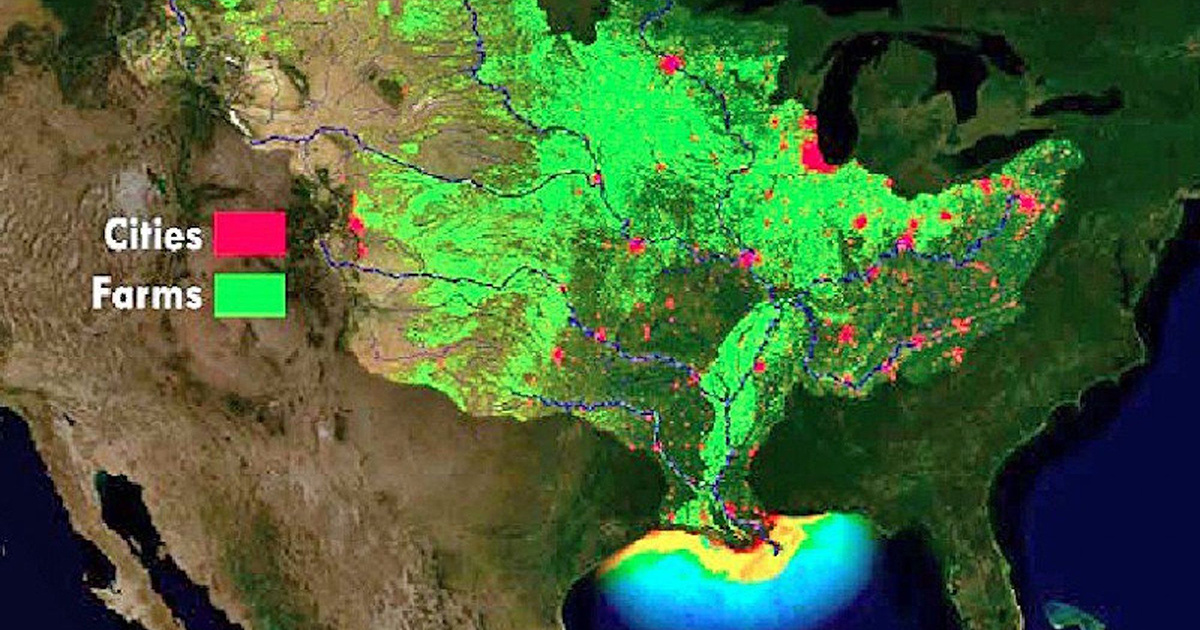

The Gulf of Mexico’s dead zone is a result of nutrient pollution, including nitrogen and phosphorus from urban environments and farms, traveling through the Mississippi River watershed and into the gulf, according to NOAA’s press release.

NOAA pointed to the overwhelming spring rains along the Mississippi River, which led to record high river flows and flooding, as a major contributing factor to this year’s sizeable dead zone.

The record flooding brought a substantial amount of pollutants into the water. “This past May, discharge in the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers was about 67 percent above the long-term average between 1980 and 2018. USGS estimates that this larger-than average river discharge carried 156,000 metric tons of nitrate and 25,300 metric tons of phosphorus into the Gulf of Mexico in May alone. These nitrate loads were about 18 percent above the long-term average, and phosphorus loads were about 49 percent above the long-term average,” NOAA said in its press release.

What happens is the nitrogen and phosphorus stimulate the growth of phytoplankton, which fall to the bottom of the water and decompose with the bacteria that uses up the oxygen, creating an area with not enough oxygen to sustain life.

“The low oxygen conditions in the gulf’s most productive waters stresses organisms and may even cause their death, threatening living resources, including fish, shrimp and crabs caught there,” LSU said in a statement. “Low oxygen conditions started to appear 50 years ago when agricultural practices intensified in the Midwest.”

To prevent the problem in the future, a task force of federal, state and tribal agencies from 12 of the 31 states that comprise the Mississippi River watershed set a goal of reducing the dead zone from an average of about 5,800 square miles to an average of 1,900 square miles, but that number is far from today’s reality, according to NBC Dallas-Fort Worth.

“While this year’s zone will be larger than usual because of the flooding, the long-term trend is still not changing,” said Don Scavia, an aquatic ecologist at the University of Michigan who contributed to the NOAA report, in a University of Michigan statement. “The bottom line is that we will never reach the dead zone reduction target of 1,900 square miles until more serious actions are taken to reduce the loss of Midwest fertilizers into the Mississippi River system.”

In the meantime, farmers along the Mississippi can build embankments to stop runoff, diversifying their crops and using sustainable perennials like wheat grass, which will hold more nitrogen and soil in the ground since it has a longer root than corn and soybeans, according to CNN.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe