Australia Throws Great Barrier Reef a $300 Million Lifeline, but Will It Cut Emissions?

Australia's Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program will further investigate 43 potential fixes for the Great Barrier Reef in a wide-scale rescue effort. Australian Institute of Marine Science

The Great Barrier Reef is in trouble. The Australian government is trying to buy its crown jewel some time, but is it willing to support what the reef needs most — a reduction in emissions?

A few weeks ago, the world’s greatest coral reef suffered its third major bleaching event in five years, the most widespread to date. The frequency and severity of the bleachings have caused some scientists to speculate whether the reef has reached a tipping point of no return.

On Thursday, Minister of the Environment Susan Ley announced the launch of the research and development (R&D) phase of the government’s Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program (RRAP) to combat the declines the reef is experiencing.

Following a two-year feasibility study led by the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS), a list of 160 potential fixes was whittled down to 43 promising concepts that will be funded for further investigation.

AIMS Chief Executive Paul Hardisty described how the R&D phase will “provide the scientific basis to help the reef survive in the coming decades,” noted a media statement. The program is designed to uncover adaptations for the reef that are cost-effective, safe, and acceptable to the public and regulators, Hardisty said.

But how effective can an adaptation and resilience program really be against the backdrop of ever-increasing global emissions and ocean temperatures?

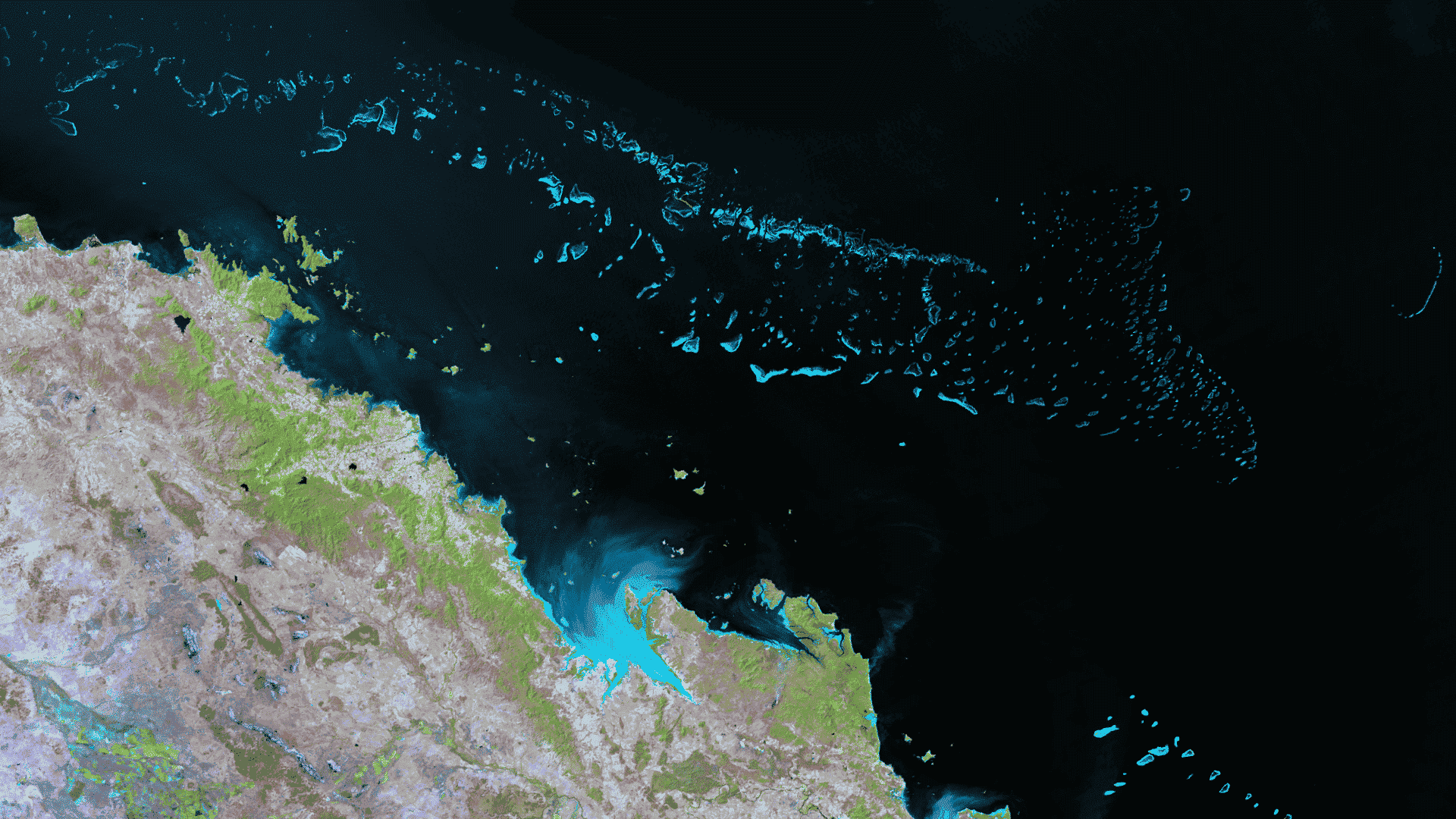

The Great Barrier Reef is the world’s largest coral reef ecosystem. Stretching 2,300 km along Australia’s northeast coastline, this complex of shallow water reefs and islands is home to thousands of species of fish, invertebrates, algae, reptiles, birds and algae. This image, taken by the VIIRS sensor on the Suomi NPP satellite on Aug.19, 2017 uses the high resolution SVI 3, 2, and 1 bands, commonly referred to as “natural color” RGB. NOAA National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service (NESDIS)

The feasibility study found that global warming might kill the entire Great Barrier Reef by as early as 2050, reported Hack.

Most tropical coral reefs will disappear even if heating can be limited to 1.5°C, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said, reported The Guardian. Reefs will still be “at very high risk” at 1.2°C warming, and the globe is already over 1°C since the Industrial Revolution, The Guardian explained.

The feasibility report concluded, “We are facing the very real prospect that, within a generation and without concerted action to reduce emissions and help drive adaptation and faster recovery from damage, the Great Barrier Reef as we have known it will cease to exist,” reported Hack.

To avoid this, the scientists are calling for an intervention at a scale never seen before, and they’re trying to find adaptation solutions before climate change destroys what remains of the reef, The Guardian reported.

Daniel Harrison, a biological oceanographer at Southern Cross University, led one of the 43 experimental trials being funded for further research.

“This is a race against time,” he said to The Guardian. “If we can go really hard on emissions and meet or beat the Paris [climate] targets, then these interventions have the potential to help get the reef to a sustainable future – but only under that very aggressive emissions reduction scenario.”

Therein lies one of the historically sticky points for environmentalists when it comes to Australia’s “hypocritical” environmental protection efforts contrasted against its broader, coal-friendly environmental policies, reported Fortune.

In 2017, Greenpeace called the government’s “coal crush” the real threat to the Great Barrier Reef because it “[ignored] the simple reality of climate change.” In 2018, Australia invested 9 million into saving the reef. The government concurrently promoted the building of new coal mines, which fuel global warming that harms the reef.

In 2019, Australia continued its “love affair with fossil fuels,” setting new record highs for emissions pollution. That same year, the marine park authority approved plans to dump one million tonnes (approximately 1.1 million U.S. tons) of sludge onto the reef.

As recently as December 2019, coal advocate and current Prime Minister Scott Morrison received backlash for vacationing in Hawaii and seeming “remarkably indifferent” while bush fires devastated the country, reported The Washington Post. The fires were exacerbated by climate change and the spike in greenhouse gases caused by the burning of fossil fuels, explained The Washington Post.

In response, Morrison said, “Our emissions reductions policies will both protect our environment and seek to reduce the risks and hazards we are seeing today,” reported The Washington Post.

The realities of climate change and coral bleaching have led even the scientists spearheading this latest effort to save the reef to characterize the RRAP as a long shot, reported Hack.

AIMS principal research scientist Ken Anthony told The Guardian, “It’s a bit like the Apollo 11 mission. It really is on that scale.”

Hardisty also metaphorically compared the new program to the “high-risk but successful U.S. mission to put a man on the moon before the end of the ’60s,” reported Hack. He agreed that success might seem like a “moonshot,” given the current situation on the reef and global emissions, but optimistically added, “If we work hard and are smart and are courageous we can turn this around,” reported Hack.

The R&D phase will be funded by the Australian government and a consortium of universities and marine studies institutes. The government committed 0 million for the next five years, and that figure could jump to 0 million with promised donations from the private sector and in-kind investments from R&D providers, noted a government press release.

The feasibility study found that the efforts could result in a net benefit to Australia of tens of billions of dollars, much greater than the initial investment, the investment case said.

- 'The Great Barrier Reef is on a Knife Edge': Reef Faces Third Major ...

- Australia Downgrades Great Barrier Reef Outlook to 'Very Poor ...

- Great Barrier Reef Authority Warns That Climate Action Is Needed ...

- 2020 Great Barrier Reef Bleaching Event Is Most Widespread to Date

- Scientists Discover Massive Coral Reef Taller Than Empire State Building - EcoWatch

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe