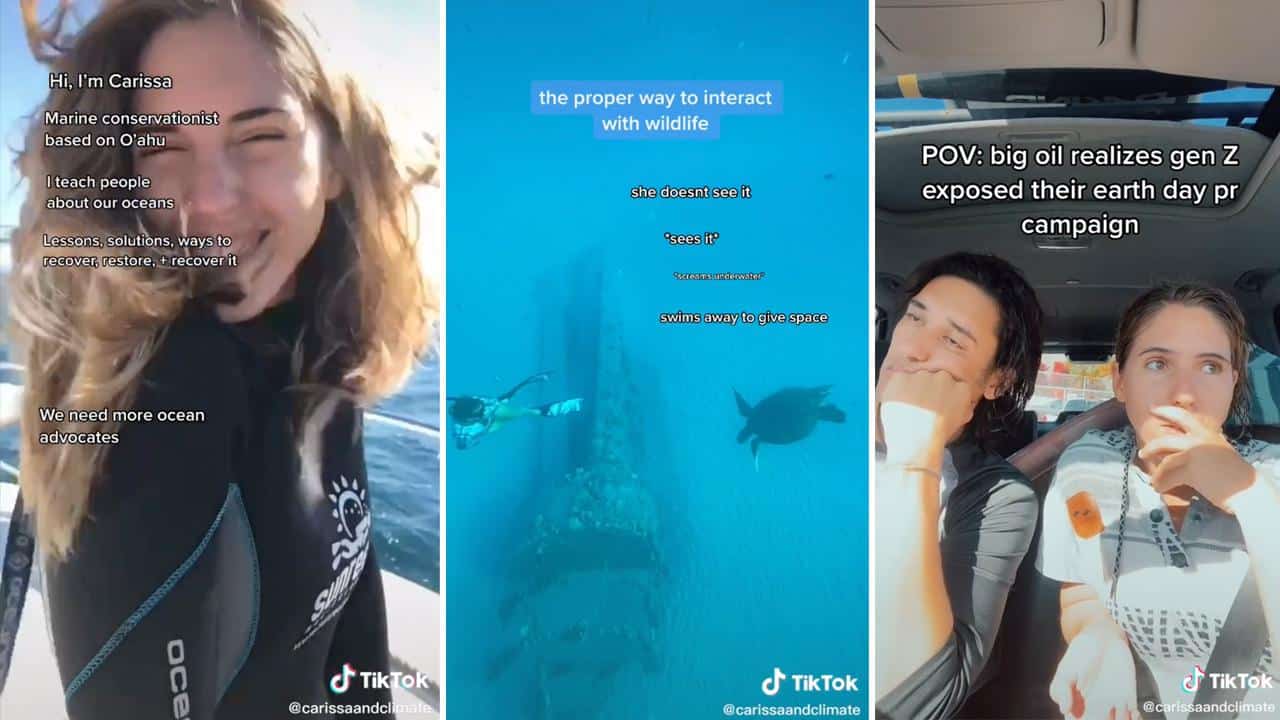

carissaandclimate / TikTok

By Claire Wiley

In March, Carissa Cabrera posted a video of severe flooding near her home in Hawaii to TikTok in response to a comment on her profile reading “climate change is not real.”

Over footage of a swollen river and cars navigating badly flooded roads, a voiceover says: “This isn’t global warming. This isn’t climate change. Let’s call it exactly what it is: climate crisis.”

The 10-second video has been viewed over 300,000 times.

[tiktok_embed https://www.tiktok.com/@carissaandclimate/video/6938210628746218757?is_copy_url=1&is_from_webapp=v1 expand=1]

Cabrera is a marine biologist and member of EcoTok, a collective of young influencers posting to video-sharing platform TikTok about environment and climate topics like carbon capture, food waste, biodiversity and recycling.

EcoTok launched in July 2020 after Las Vegas high school student Alex Silva, who mainly posts videos on low-waste living under the name “ecofreako,” sent an Instagram message to fellow activists with the idea.

The group has grown to 16 members, including students, scientists, environmental educators and civil servants, and has worked with organizations such as TED Countdown, an initiative to encourage climate action, and Bill Gates’ social venture capital firm Gates Ventures on campaigns for their eco-initiatives.

Like most users of TikTok, EcoTokers post fast-paced content featuring upbeat soundtracks, dances and colorful captions to make their green message go viral.

And they’re not the only environmental activists doing so. Other young influencers are reaching millions of people with their posts. The hashtags climate change and sustainable have well over a billion views between them.

Creating Viral Green Videos

Cabrera was used to teaching marine conservation in classrooms of around 30 people. TikTok’s appeal is in the numbers she can reach on the wildly popular app, which has now been downloaded more than 2 billion times, largely by Generation Z — those in their teens and early twenties.

Her videos, posted under the username “carissaandclimate,” have been liked over a million times.

“TikTok is not really a social media app; it can be a learning resource. Gen Z wants the tools and resources, and they want it in a fun way,” said Cabrera, who works with The Conservationist Collective, a small company using media and educational campaigns to promote ocean protection.

In her videos, the biologist usually sticks to her area of expertise: the oceans. To bump the chances of going viral, she keeps her content under 30 seconds and tells viewers what it’s about in the first three.

Gen Z eco-influencers are taking to TikTok to get out their green message.

“You have to [take] this super-dense topic and make it viral material,” she said. “Whereas a lot of the viral material that I see on TikTok could be dances or comedy. How do you make science very fun for everyone?”

She wants to make something memorable, re-watchable, and shareable — with the goal of mobilizing people.

But not everyone thinks TikTok viral videos necessarily translate into real-world action. Sophie Moore, an 18-year-old high school student and TikTok user in California, is active in various environmental and social justice causes but thinks the platform isn’t the place for climate activism.

“I think most people use TikTok as a form of mindless entertainment, to escape from school,” she said. “TikTok is a more passive form of engaging with the climate justice movement. Because climate content is just mixed into my other stuff [in the TikTok feed], it’s easy to see it, like it and then move on.”

Key Ingredients for Real-World Activism

Still, some evidence suggests that TikTok can encourage grassroots political organizing. In June 2020, hundreds of teenage TikTok users said they had a hand in trying to sabotage a rally for then US President Donald Trump. Users registered for tickets to attend with the plan of not showing up and encouraged others to do the same.

In Indonesia, young people have used the app to protest labor law reforms. And following George Floyd’s murder, the platform saw a surge in Black Lives Matter videos.

Sander van der Linden is professor of social psychology in society at Cambridge University in England and editor-in-chief of the “Journal of Environmental Psychology.” He says viral social media campaigns “can result in action” if they do three key things: exert “social influence” by challenging others to join in, support a moral cause and elicit emotion.

But the effects are often short-lived, according to his research on the topic. For instance, the ice-bucket challenge raising awareness of ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, attracted lots of attention for a brief period in 2014 but just as quickly tapered off. Despite this, however, the ALS Association said it was able to increase annual research funding by 187% thanks to the $115 million raised from the challenge.

While van der Linden says he’s not aware of any research specifically looking at TikTok’s climate videos, his social media research suggested that it’s difficult to generate long-term momentum behind the climate movement. Most don’t see climate change as a moral cause or experience strong emotions around it, he added.

Van der Linden wonders if there’s some “preaching to the choir.” He and researchers at Yale University identified something they dubbed “The Thunberg Effect“: Those who identify as environmentalists and know of Swedish school-striker Greta Thunberg have a stronger belief that collective action can help to fight climate change.

Cabrera disagrees. TikTok is a participatory platform that allows users to easily borrow, repurpose and answer each other’s videos. She says her viewers get in touch to let her know they’re taking action by, for example, signing petitions or making small changes to their habits.

But it’s not all about individual responsibility, she adds.

“We also want to be part of this larger, more nuanced conversation about how the responsibility of climate action shouldn’t just be falling on the backs of individuals,” she said. “We want people to feel like we need to hold leadership accountable.”

A Tide of Misinformation

Van der Linden adds that misinformation about climate change on social media generally can have huge consequences because it’s such an important existential threat that “if you mislead people, it could have incredible consequences.”

That misinformation is widespread and covers everything from renewable energy to the scientific consensus on climate change.

“It really spans the whole spectrum and that’s why it’s so difficult to tackle,” he said.

It’s something Cabrera and the EcoTok team are aware of. Each of their videos is shared with the entire collective before posting, and members give feedback. Of course, not all climate content on TikTok undergoes the same checks.

But Moore says that if any video she’s watching “seems far-fetched,” she will check the comments, where other users call out the content as fake.

Unlike some TikTok climate activism with catastrophic messages about time running out, EcoTok and Cabrera also try to avoid “doom and gloom” content, while conveying the urgency of the crisis.

That’s why Cabrera’s TikToks usually include a simple task. For example, one video suggests “three bathroom swaps” to reduce plastic.

“We need everyone to be an environmentalist,” she said. “People need to feel motivated and inspired to do that, instead of guilted into it. But there’s this catch-22 because this is a climate emergency. We don’t have that much time.”

Reposted with permission from Deutsche Welle.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe