20 Year David and Goliath Fist Fight Saves Patagonia’s Futaleufu

A History of Democracy and Free-Flowing Rivers

Chilean environmentalists and global whitewater aficionados are celebrating the happy ending to the tumultuous 20-year battle to save Patagonia’s Futaleufu River. On Aug. 30, Endesa Chile, subsidiary of Enersis and part of Italian-controlled energy consortium Enel, formally relinquished all claims to Chile’s iconic whitewater mecca, and similar stakes in other Chilean rivers.

Endesa sought to build two dams on the Futaleufu that would capture its water for energy generation while inundating the river’s spectacular landscapes—the 800-megawatt La Cuesta facility nine miles from the village of Puerto Ramirez and the 400-megawatt Los Coihues dam across Inferno Canyon at the gateway to the river’s prime whitewater.

The picturesque farming communities above that dam would have drowned beneath 75 feet of water; mountainous rapids below the dam would survive only in the memories of those lucky enough to have experienced the unbridled river. The Spanish company hoped to sell the power from these installations to Argentina, or otherwise up north through Chile using a massive transmission line that was never built.

In a statement to the Chilean government, Endesa tabulated the factors behind its decision as:

- “the high annual cost for the company to maintain water rights without using them”

- the technical and economic difficulties facing the damming project

- and, most notably, the lack of “sufficient support from local communities”

Fierce local opposition caused Endesa, two years ago, to suspend immediate plans to dam the Futaleufu, which has one dam near its headwaters in Argentina but flows free for 65 miles through Chile. Trapped between unyielding popular resistance and the escalating costs of its water rights, Endesa abandoned the project altogether. Endesa said its decision represents a $52-million haircut for its shareholders.

“This is an extraordinary triumph for Patagonia,” said Patrick Lynch, staff attorney and international director at Futaleufu Riverkeeper. “The victory belongs to a half dozen activist groups composed of local farmers, river guides, fishermen and outfitters, and to the thousands of river lovers around the world and the international environmental groups who supported the community fighting the dam.“

Reflecting on the long battle, Lynch told me, “It was always such an unlikely coalition. And yet this community won a bruising 20 year David and Goliath fist fight. We beat back an all-powerful international utility company that owned this river for more than 20 years. Now we need legal reforms to put an end to a corrupt system that still reward damming rivers for profit.”

The Futaleufu played a symbolic role in Chile’s struggles to restore her democracy, still reeling from two decades of dictatorship under General Augusto Pinochet. “Pinochet’s regime was old school European corporatism,” the Chilean environmental and human rights activist, Juan Pablo Orrego, explained to me in 1993 soon after Pinochet left power. “He followed Mussolini’s scheme to merge state and corporate power and that meant handing Chile’s publicly owned natural resources—including our rivers—over to private corporations.”

Every tyranny includes efforts by powerful interests to privatize the public commons, but Pinochet’s regime turned the ideology of privatization into a religion. In what is now regarded as a cataclysmically failed social experiment in voodoo economics, Pinochet turned Chile over to a group of right wing theoretical economists from the University of Chicago, entrusting them with authoritarian control over virtually every aspect of economic life in Chile.

These acolytes of “free market” guru Milton Friedman, the so called “Chicago Boys,” used their unlimited power to impose a barbaric austerity on Chile’s poor and middle classes. They slashed taxes on the rich and corporations, discarded vital subsidies for fuel, school milk and other food staples, eviscerated labor unions, cut education and healthcare, and repealed environmental, financial and trade regulations. In an orgy of privatization, they auctioned off Chile’s public assets—including her roads, airports, airlines, telephone and electric utilities, her waterways and forests to multinational corporations at fire sale prices. “They literally liquidated our commonwealth for cash,” Orrego observed. “They obliterated Chile’s public spaces.” Pinochet’s henchmen gave away every Chilean river to private companies for damming.

These anti-democratic reforms were naturally unpopular with many Chileans, and Pinochet jailed, tortured and killed his program’s critics, murdering 3,000 dissenters, imprisoning 20,000 and forcing another 200,000 into exile.

My family has had a long history of friendship with Chile. In the early 1960s, Chile’s leftist democratic president, Eduardo Frei Montalva, became the closest Latin American ally of my uncle, President John Kennedy. Frei helped craft the blueprint for JFK’s Alliance for Progress. Both men hoped the “Alianza” would break the strangle hold of Latin America’s oligarchies who presided over feudal economies characterized by vast gulfs between rich and poor.

The oligarchs protected their wealth and privilege through seamless relationships with the military caudillos who ruled their nations with brutal dictatorship. That ruling coalition fortified itself in symbiotic relationships with all-powerful U.S. multinationals like Anaconda Copper, United Fruit, IT&T and Standard Oil, to whom the local oligarchs ceded their nations’ natural resources in exchange for a share of the profits. These colonial style arrangements gave the oligarchs unimaginable wealth and power, kept their people in desperate poverty and gave rise to a new derisive sobriquet for these countries, the “Banana Republic.”

Prior to JFK, U.S. foreign policy was to nurture these powerful oligarchies which unctuously served the mercantile interests of American corporations. But these policies, for JFK, represented a stark departure from American values—including our national anti-colonial heritage—and caused appalling injustice and poverty that was easily exploited by communist revolutionaries. Frei and Kennedy designed the alliance as a suite of reforms to rebuild Latin America as a collection of just, democratic, middle class societies. Chile, the continent’s beacon of middle class stability, democracy and freedom would be the template.

My father’s first public break with President Lyndon Johnson following JFK’s assassination was over Johnson’s subversion of the alliance. My father believed that the new U.S. president had abandoned the alliance’s idealistic goals and returned U.S. policy to its historical role of supporting the oligarchs and fostering corporate colonialism.

In 1964, my father infuriated Johnson by visiting Chile and advising its intellectuals and government officials to nationalize the U.S. oil and mining interests that were robbing the nation’s natural wealth. My father engaged in a heated debate with communist students at the University of Concepcion who showered him with spit, eggs and other missiles. He then made a harrowing trip headfirst into the depths of an Atacama copper mine on a tiny sled to meet with beleaguered miners. He returned to the surface to chastise the dismayed mine owner for mistreating his workers.

Just after dawn on the morning of June 29, 1973, I found myself with four others, including New York Times reporter Blake Fleetwood, on a remote Andean ridge near Chile’s frontier with Argentina earnestly digging in the deep snow to escape a hail of gunfire from half a dozen carabineros crouched in the valley 100 meters below us. The squadron had pursued us from the nearby military base as we climbed on sealskins for a day of backcountry skiing. Believing we were trying to escape across the border, they soon captured and detained us. The nation was on high alert. Unbeknownst to us, a tank battalion, that morning, had launched a coup against the regime of Chile’s socialist president, Salvador Allende.

I had traveled to Chile for the Atlantic Monthly to write about the Nixon administration’s efforts to destroy Chile’s economy—”Make the economy scream,” he had ordered the CIA in 1970—and to overthrow Allende, the duly elected president of Latin America’s oldest and most stable democracy. (Our nation would later learn that Nixon had accepted a hefty bribe from IT&T, which feared Allende’s plans to naturalize their company).

Colonel Roberto Souper’s so called “Tank Coup” quickly failed, but three months later, on Sept. 11, Salvador Allende died in a firefight as General Pinochet’s troops invaded the presidential palace. The following year at a Senate Refugee Committee hearing chaired by my uncle, Senator Edward Kennedy, junta representatives warned me never to return to Chile. From the moment Allende died, Teddy had been scrambling to rescue Chilean descendants from Pinochet’s murderous wrath. Chile’s Foreign Minister Heraldo Muñoz, former United Nations ambassador, told me that he owes his life to Teddy’s timely intervention. Teddy’s 1974 bill, the so called “Kennedy Amendment,” froze U.S. arm sales to the junta. When Teddy tried to visit Chile in 1986, Pinochet arranged violent riots to muzzle him and drive him from the country.

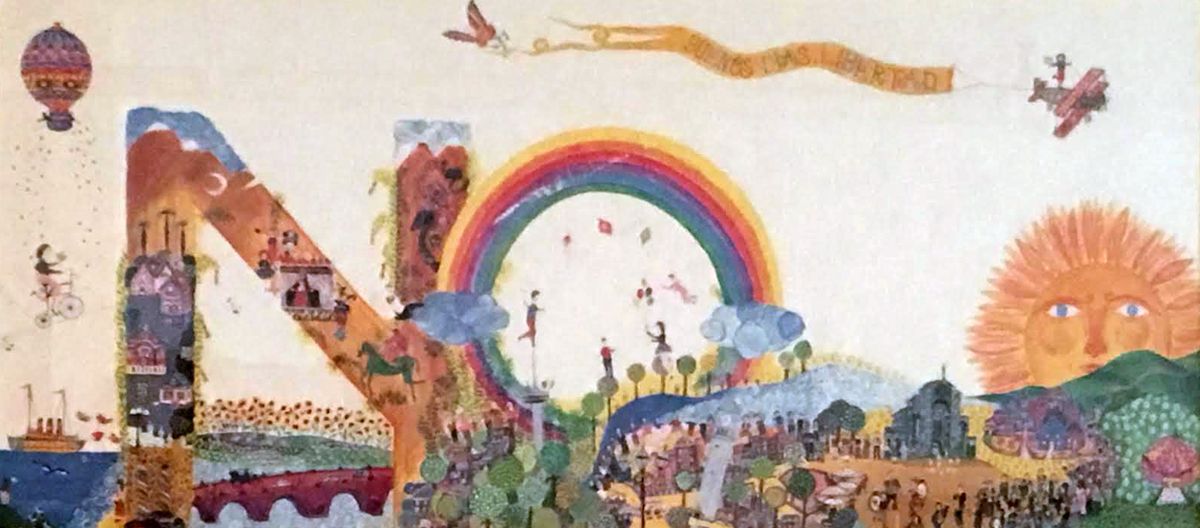

Working with Chile’s democratic resistance, Teddy authored and passed legislation conditioning U.S. aid to Chile on a national referendum in which the Chilean people would be allowed to vote “si” or “no” on Pinochet’s continued rule. Chile was desperate for that U.S. aid package; by then, the Chicago Boys’ “reforms” had wrecked the Chilean economy and dismantled the finest health and education systems on the continent.

Chile’s industrial base was in ruins; unemployment had risen tenfold. Chile was suffering from 375 percent inflation and a runaway national debt. Chile’s resounding “No” vote in the plebiscite finally drove Pinochet from power. In 1990, Teddy returned to a hero’s welcome in Chile to attend the inauguration of Pinochet’s democratically elected successor, President Patricio Aylwin.

My entire family was beyond proud when in September 2008, Chile’s first woman president, Michelle Bachelet came to our home in Hyannis Port to award Teddy Chile’s highest civilian honor, the “Order of Merit” for his long support for democracy in Chile. Bachelet and her mother were among the Chileans Pinochet had tortured and jailed. Bachelet’s father, an air force officer, was tortured to death in prison.

Even after he relinquished power, Pinochet’s legal legacy continued causing mischief against the nation’s people and their right to water. Pinochet had embedded the privatization of all Chile’s water flows into key parts of the nation’s Constitution and Water Code. To make sure that free-flowing rivers can never remain in public hands, the framework provides that ownership of Chile’s water rights no longer belong to the public. Instead they belong to the first corporation to claim them. The law was finally revised in 2005 to punish corporate owners with escalating fees for not using the rights, but they can get the fees back once they propose and begin construction of a dam. These fees escalate over time, gradually topping millions of dollars per year for some rivers. The first battleground for challenging Pinochet’s corporatist water regime was the fight to save the Biobio from dam builders in 1993.

The Biobio River was Chile’s crown jewel. By the late 1980’s it had already become Latin America’s—and arguably, the World’s—premier whitewater destination. Whitewater paddlers considered it the equivalent of the Colorado River, the world’s gold standard of whitewater, for its breathtaking rapids and magical scenery. The Biobio plunged through a Grand Canyon scale gorge, but unlike the naked rock that frames the Colorado, the Biobio’s lush climate had festooned its canyon walls with hanging gardens and watered them with five massive waterfalls that cascaded from the high plateau—all of this in the shadow of a smoking snow-capped volcano!

In 1993, following the collapse of the Pinochet Regime and the democratic election of Patricio Aylwin, I was among a small contingent of Natural Resources Defense Council attorneys who accompanied Mapuche Indian leaders and Chilean environmental activists on the largest expedition ever to run Chile’s Biobio River. Juan Pablo Orrego, one of the founding fathers of the Chile’s modern environmental movement, accompanied us as president of the grassroots Grupo de Accion por el Biobio.

Orrego observed to me, at that time, that while democracy had nominally returned to Chile, Pinochet had already given away virtually all the public assets that made democracy meaningful. The return of democracy, Orrego argued, was therefore illusory. Chile, he said, had reverted to a colonial model with its natural resources controlled by foreign corporations. Pinochet had given away Chile’s entire commonwealth to private companies.

“We supposedly have democracy, but it is a democracy without teeth. A nation can’t have a true democracy without sovereignty over its lands and infrastructures,” Orrego told me.

The Biobio, once the diadem of Chile’s patrimony, was now the wholly owned asset of private utility—Endesa. With the Chilean government’s blessing and World Bank loans, Endesa planned a series of six dams on the river that would bury its stunning landscapes. Working with Orrego, the Mapuche-Pehuenches, NRDC and the Chilean Commission on Human Rights, our coalition launched an international campaign to save the Biobio. We attacked the critical flaws in Endesa’s plans, including the fact that the dams were to be built in the middle of an earthquake fault at the base of two volcanoes. In meetings with World Bank officials, we pressured the institution to launch its own internal investigation. In the end, we managed to force Endesa to drop its proposals for all but a single dam—the Pangue. Many people saw this as a victory. I did not. The Pangue and its 1,250-acre reservoir in indigenous territory ruined the Biobio’s viewshed and its best whitewater. Ten years later, Endesa succeeded in building one more dam on the Biobio, called Ralco, which displaced 97 Pehuenche families and even flooded a sacred graveyard. I have never been able to bring myself to return to that desecrated paradise.

In 1993, my friend Eric Hertz—a white-water outfitter, river conservationist and founder of Earth River Expeditions—told me he had found a river nearly the Biobio’s equal. Hertz had spent a lifetime searching for the perfect river. He had finally discovered it 600 kilometers south of the Biobio, in Chilean Patagonia.

Situated between snow-capped glaciers and rugged saw-tooth mountains reminiscent of the Tetons, the Fu flows through narrow canyons and verdant valleys, where river runners find an irresistible mix of wilderness and charming pastoral landscapes. Chattering ibis, spoonbills and plovers flock over grazing sheep as Patagonian gauchos, sporting sheepskin chaps trimmed with heavy fur, ride their criollo ponies or drive yoked oxen pulling wooden wagons along the banks. Stunning granite cliffs and outcroppings at the valley fringes frame a fairytale landscape of rustic farms, broken forests, orchards and alpine meadows.

Intrepid kayakers who had ventured into southern Chile the previous year said that violent rapids made the Futaleufu River unrunnable by raft. But Hertz and his partner at Earth River, the Chilean white-water expert Roberto Currie, made an expeditionary first decent in 1993 and figured out how to safely navigate what today is the most intensive stretch of commercially rafted whitewater rapids in the world. Ever since then, I try to make an annual trip to the Fu with my family and friends each March. Kayakers and rafters and fishermen flocking to the river soon transformed the tiny Alpine village of Futaleufu into a bustling river outfitter’s haven.

Several elements combine to make the Fu an incomparable outdoor adventure: the breathtaking scenery, the series of more than 30 tightly packed and formidable Class IV and V rapids, the hospitable climate, the cultural charms of its farm community of vaqueros and homestead pioneers, the incomparable campsites and hiking trails, the absence of biting insects and the shocking teal color of the river’s gin clear waters—a feature that nearly always prompts a double-take at first sight; when actress Julia Louis- Dreyfus caught her first glimpse of the Fu’s show stopping blue-green luminescent, during a 2003 expedition, she gave an astonished laugh, “Did they dye it,” she asked me, “like at Disneyland?”

[vimeo https://vimeo.com/182256583 expand=1]

The Fu is also a world class fishing destination. During my annual pilgrimages to the Fu, I customarily fish from the bow of my raft as I take in the scenery between the rapids. The small bays and pockets of still water along the Fu’s banks and below each rapid almost always yield trout or large salmon that dart, voracious and aggressive, from hiding places under the branches of willows and osiers, and from beneath the Fu’s granite walls. For mile after river mile on virtually every cast, whether with fly or spinning rods, an angler can watch brown trout follow a lure through the clear cyan water.

The Fu has a pebbled bottom, clean water, rich vegetation and an alkaline pH, conditions that are ideal for trout. Besides brown trout, coho, Atlantic salmon, chinook and other North American imports also frequent the Fu, growing upward of 60 pounds. I’ve fished in most of the states, including Alaska, and in most of the provinces of Canada, and in Latin America from Costa Rica to Tierra del Fuego. But I’ve rarely seen a waterway with consistently large salmonoids in such abundance. A local friend, Adrei Gallardo, took a 39.9-pound brown trout from the Fu on a handline—the Latin American record. Gallardo told me that he subsequently refused to relinquish the mount to representatives of Munich’s Hunting & Fishing museum, despite a $20,000 offer—the equivalent of a two-year salary.

Julia Louis-Dreyfus stands among a parade of international celebrities who have visited the Futaleufu over the past two decades to run its rapids and fight the dams—Dan Ackroyd, Donna Dixon, John McEnroe, Patti Smith, Glenn Close, Brad Hall, David Chokachi and Richard Dean Anderson, to name a few. They came to support the valley’s voiceless vaqueros, shepherds, fishermen, kayak paddle guides, whitewater companies and landowners. For all of those who participated in this battle, Aug. 30 was a time of celebration.

But Lynch cautions against complacency. “We can’t celebrate with our paddles in the air just yet,” warned Lynch. “In Chile they call the forces that want to privatize those rivers zombies. These are zombie dams. Every time you think you’ve killed a project, it comes back from the dead.

“The era of big dams in Patagonia is not over yet. Endesa still has rights over the Baker and Pascua Rivers. And other companies still have permits to build dams on other wild and scenic rivers like the Cuervo.”

And Lynch still worries about the Fu. General Augusto Pinochet died in 2006 under house arrest, awaiting trial for corruption, torture and murder, but in a very real sense Pinochet continues to rule Chile from the grave. Because of the reactionary water regime devised by the Chicago Boys, the water rights that Endesa relinquished will not long remain in public hands. Under Chile’s Water Code, any hydroelectric company that wants to seize the river for damming may step into the vacuum left by Endesa and claim the Fu for itself. Lynch has a wary eye on the Chinese with their bottomless appetite for Latin America’s natural resources.

“China is the world’s leading dam builder,” he said. “They would be the most likely international suitor.”

Looking forward, Lynch said, “Our job is to help show international water speculators—called piratas here—that it’s a risky business to try to build a dam in Chile. We need to let them know that the people have had enough. If they come here, they are going to have a Donnybrook on their hands.”

Lynch understands that river conservation is as difficult as democracy. There are no permanent victories. The only thing we ever really win is the opportunity to keep fighting.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe