Only a little more than one-third of the world’s 246 longest rivers remain free-flowing, drastically reducing the diverse benefits that healthy rivers provide to people and nature everywhere, according to a new study by World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and partners.

A team of researchers from WWF, McGill University, and other institutions studied about 7.5 million miles of rivers worldwide to determine whether they’re well connected. They found that only 37 percent are free-flowing — meaning they’re largely unaffected by human-made changes to its flow and connectivity. Dams built in the wrong place and climate change are impacting river health worldwide, and the planet’s remaining free-flowing rivers are largely restricted to remote regions of the Arctic, the Amazon Basin and the Congo Basin.

Vanishing Free-Flowing Rivers

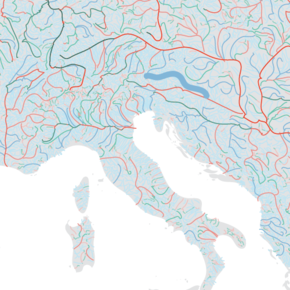

Long free-flowing rivers are vanishing. Around the world, rivers are becoming increasingly fragmented by dams and other development — such as roads or dikes — endangering freshwater ecosystems and the people and wildlife that rely on them. Free-flowing rivers transport water, nutrients and species that sustain biodiversity and benefit millions of people. To help countries and communities better protect their freshwater resources, WWF and partners came up with a technical definition of a free-flowing river and then created a first-of-its-kind, scientifically backed map — a comprehensive inventory of the world’s last free-flowing rivers, rivers with good connectivity and impacted rivers.

1. Mura River — Slovenia

Called the “Amazon of Europe,” the Mura River provides critical habitat for endangered and rare species such as otters, Danube salmon and black stork. After urging from WWF and others, in February 2019, the Slovenian government signed an agreement to stop all hydropower plant development that would devastate the Mura.

2. Usumacinta River — Mexico

In June 2018, guided by WWF and partners, Mexico established water reserves across nearly 300 river basins, guaranteeing water supplies for 45 million people for the next 50 years. Ninety-three percent of the water in the Usumacinta — the longest, most biodiverse river in Central America and one of Mexico’s — is now federally protected.

3. Bita River – Colombia

The Colombian government named the Bita River basin a Ramsar site — a wetland of international importance — in June 2018, thanks in large part to the work of WWF and partners. Covering 825,000 hectares, it’s the largest of the country’s 11 Ramsar sites and one of the few in the world to encompass an entire free-flowing river watershed.

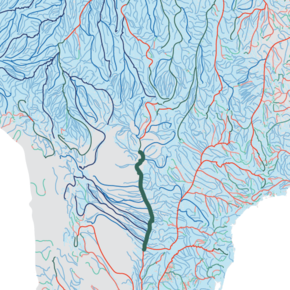

4. Paraguay Basin — Brazil

More than 100 dams planned for the Upper Paraguay Basin could hurt water supplies, biodiversity and local communities. After tremendous efforts from a coalition including WWF, Brazil’s National Water Agency suspended new dam development there until May 2020. But the suspension only applies to rivers under federal jurisdiction — so just 20 of the 100 dams will be suspended.

5. Luangwa River — Zambia

The Luangwa, which is free but impacted by a dam on a nearby river, is at risk. A proposed dam at Ndevu Gorge threatens this wild waterway, which shelters abundant wildlife and human populations. In Zambia, WWF is advocating on behalf of people and nature, pushing the government to reconsider its energy plans and ensuring that local people maintain their rights to natural resources.

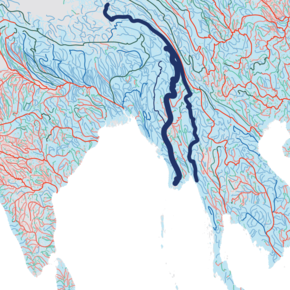

6. Irrawaddy and Salween Rivers — Myanmar

In Myanmar, an in-depth Strategic Environmental Assessment recommended that the main stems of the Irrawaddy and Salween rivers — two of the last long free-flowing rivers in southeast Asia — should remain free of dams. But there is still risk, making alternative energy such as solar and wind power even more important for people, rivers, and the country’s economy.

Learn more about free-flowing rivers and WWF’s efforts to protect them.

Mapping Downs

Dams provide safe drinking water and electricity to millions of people. But when built in the wrong place — for instance, a river’s main stem — they can impede a river’s flow, causing drastic declines in biodiversity and affecting fish migration, agriculture and livelihoods. Today there are more than 60,000 major dams around the world — a number that’s increasing to meet demand for hydropower. WWF is helping national governments, industries and developers consider both the long-term impacts on local people and habitats and other potential alternative options for meeting water and energy supply needs, as well as helping them identify the best opportunities for river restoration projects. Solar and wind prices are going down, making them attractive alternatives.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe