Beyond Carbon Storage: New Study Highlights Other Ways Forests Keep Us Cool

If all of the world’s forests disappeared tomorrow, how much hotter would the world be?

A first-of-its-kind study published in Frontiers in Forests and Global Change Thursday found that the world’s forests keep the planet around 0.5 degrees Celsius cooler than it would be otherwise. That 0.5 degrees is the same crucial difference between two degrees Celsius of warming and the 1.5 degree limit that scientists say we must stop at if we want to avoid the worst impacts of the climate crisis.

“Forests are doing that for us already,” study lead author and University of Virginia professor Deborah Lawrence told EcoWatch.

But the big news from the study isn’t merely that forests keep the planet cool. Their importance as carbon sinks has long been documented by scientists and touted by policy makers. Rather, the research is unique for considering the other ways that forests lower temperatures at both a local and global level that don’t involve drawing carbon dioxide down from the atmosphere. Accounting for these so-called biophysical effects allowed the researchers to calculate forests’ true cooling effect. Further, the study found that the band of tropical forests between 10 degrees north latitude and 10 degrees south latitude are doing the most work to keep the planet cool.

“Tropical forests are doing even more than we thought to keep us cool and to keep people safe, to keep our agricultural systems productive and to keep our cities livable,” Lawrence said.

Biophysical Effects

The paper looked at three main non-carbon related ways that forests having a cooling influence.

- Evapotranspiration: Evapotranspiration is one way that forests transform the energy they take from the sun. It describes how trees take liquid water from the soil and release it as water vapor through holes called stomata in their leaves. The process has a net cooling effect. “The canopy is like a giant air conditioner,” Lawrence explained.

- Roughness: While evapotranspiration cools the air immediately around a forest, it doesn’t cool the whole planet. But forests, by growing up to 50 meters tall, create something called surface roughness. Air traveling across the planet runs into this roughness, which creates turbulence that pushes the warm air higher. This lowers the temperature of the air at zero to five meters — ”the place where we live,” as Lawrence put it.

- Biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOC): Forests also release carbon compounds called biogenic volatile organic compounds. “It’s what makes a forest smell like a forest,” Lawrence explains. These have both a warming and a cooling effect. They promote ozone and methane, which are greenhouse gases, but they are also aerosols that reflect the sun’s energy back into space. Ultimately, the cooling effect wins out.

These biophysical effects keep things cool on both a global and a local level. The local cooling impact is perhaps the easiest to understand. The difference between a forested area and a non-forested area is like the difference between a hot parking lot and a vegetation-filled office building, Lawrence said. But the cool air created by forests can also travel farther afield, entering the oceans, for example.

“Research is making it increasingly clear that forests are even more complex than previously understood,” study co-author and carbon program director at the Woodwell Climate Research Center Wayne Walker said in a press release emailed to EcoWatch. “When we cut them down, we see devastating impacts on our climate, food supplies and everyday life. The benefits of keeping forests intact are clear; it’s imperative that we prioritize their protection.”

The Power of the Tropics

The researchers were able to prove that these biophysical effects made a difference at the global level by looking at models of what would happen to the global climate if you kept the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide constant, but removed forests. This enabled them to isolate the impacts of effects like evapotranspiration, roughness and BVOCs.

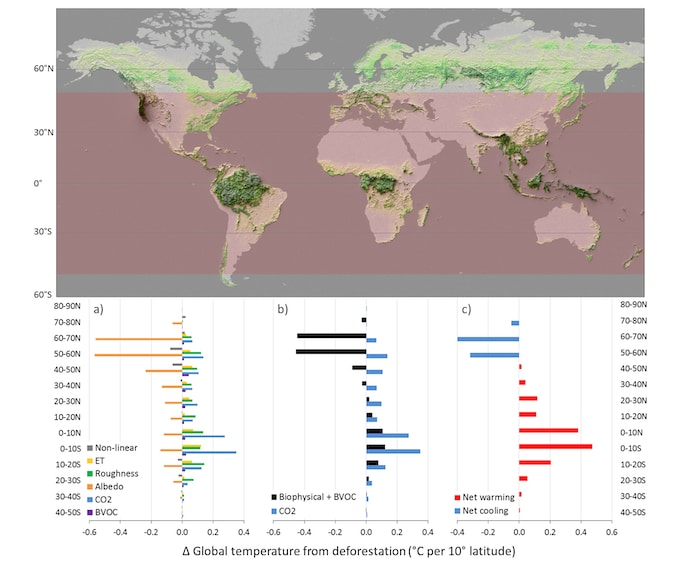

The dataset that the research team used had another benefit: It broke forests into 10-degree latitude bands, allowing them to determine the impact of deforestation from the far north to the far south, and to separate each band’s biophysical effects from its carbon-absorption.

What they found was that, for forests as far as 30 degrees to 40 degrees north latitude, both biophysical effects and carbon-absorption had a cooling effect, and deforestation therefore led to greater warming. From the mid-latitudes to around 50 degrees north latitude, biophysical effects had a slight warming impact that was canceled out by the forests’ carbon storage, so deforestation still made things hotter. Above 50 degrees north, getting rid of forests actually had a net cooling impact because biophysical effects in this region had a warming effect that exceeded the impacts of carbon storage.

Because of this, getting rid of all of the world’s forests would make the planet 0.5 degrees hotter, but getting rid of just tropical forests would make the globe more than one degree Celsius hotter. The biophysical effects of tropical forests alone cool the planet by one-third of a degree Celsius.

Why are tropical rainforests such cooling superstars? Lawrence said there are two reasons.

“We still have a lot of forest and they’re right at the equator where the sunlight energy is greatest,” she said, meaning they have the most potential to transform that energy.

Really Worried

The news comes at a perilous moment for the world’s tropical rainforests. Brazil’s space agency reported in November of 2021 that deforestation in the nation’s iconic Amazon rainforest was at its highest level in 15 years. Another study published this month warned that the forest could be approaching a “critical threshold” past which trees would begin to die back.

So how worried should we be about these developments?

“I’d say this paper says, ‘Really worried,’” Lawrence said. “I think tropical forests alone are keeping us well below the warming we would already be experiencing.”

This means that people who want to preserve forests should make an effort to do so in the tropics, where they will get the biggest “bang for [their] buck,” Lawrence said.

Forest-hosting countries like Brazil, where right-wing President Jair Bolsonaro paints environmental protection as an enemy of economic growth, should recognize that cutting down trees is actually an exercise in self harm. A study published in October of 2021 found that deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon and Cerrado actually meant that soy agriculture lost value because of extreme heat. The same month, another warned that tree-clearing in the Brazilian Amazon would expose more than 11 million more people to heat stress by 2100.

The research team emphasized that forests are not just important tools for carbon storage on the global scale — they also help local communities adapt to the climate crisis. In fact, at the local level, the biophysical effects of forests are much greater than their carbon-storage effects, leading to fewer temperature extremes no matter the time of day or year. But the global conversation does not acknowledge this.

“Despite the mounting evidence that forests deliver myriad climate benefits, trees are still viewed just as sticks of carbon by many policymakers in the climate change arena,” study co-author Louis Verchot, a principal scientist at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), said in the press release. “It’s time for policymakers at the local and global levels to realize that forests have even greater value to people and economies, now and in the future, due to their non-carbon benefits. Forests are key to mitigation, but also adaptation.”

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe