Food Apartheid: Racialized Access to Healthy Affordable Food

Huerta del Valle, a four acre organic community-supported garden and farm in Ontario, San Bernardino County, California. Lance Cheung / USDA

By Nina Sevilla

Food insecurity rates have skyrocketed during the COVID-19 pandemic, but even before March 2020, many Americans already faced challenges accessing healthy and affordable food.

“Food desert” has become a common term to describe low-income communities — often communities of color — where access to healthy and affordable food is limited or where there are no grocery stores. Living in Tucson, Arizona, in the Sonoran Desert, taught me that despite its common usage, “food desert” is an inaccurate and misleading term that pulls focus from the underlying root causes of the lack of access to healthy food in communities. The language we use to describe the issues can inspire solutions, so we should follow the lead of food justice leaders who urge us to reconceptualize “food deserts” as “food apartheid” by focusing on creating food sovereignty through community-driven solutions and systemic change.

The term “food desert” emerged in the 1970s and 80s, but in the past decade has really caught on, and is now a common concept in economic and public health fields. The racial demographics of the areas described by this term are most often Black and Latino. When comparing communities with similar poverty rates, Black and Latino neighborhoods tend to have fewer supermarkets that offer a variety of produce and healthy foods, and have more small retail (i.e. convenience and liquor) stores that have fewer produce options than in predominantly white neighborhoods.

Despite its prevalence, the term “food desert” has come under scrutiny for two reasons:

- It obscures the vibrant life and food systems in these communities.

- It implies that these areas are naturally occurring.

Sonoran Desert. Bob Wick / Bureau of Land Management

First, the word “desert” typically conjures up dramatic images of vast arid landscapes with little to no vegetation and water. Common uses of the word describe the absence of life or activity, but most deserts are full of adapted plants and have sustained human and animal populations for centuries. I fell into the trap of this misconception when I moved to Tucson. I thought it was going to be devoid of all life, but when I got there, I realized that the Sonoran Desert in Arizona, like most deserts, can be quite abundant, especially when they have the right resources.

Using the word “desert” to imply a location’s inferiority as a desolate place writes off the people who live there, as well as the flora and fauna that are actually present in deserts. The term “food desert” obscures the presence of community and backyard gardens, farmer’s markets, food businesses, and other food sharing activities that exist in these areas. As farmer and activist Karen Washington points out, “food desert” is an outsider term, used by people who do not actually live in these areas. She says, “Number one, people will tell you that they do have food. Number two, people in the ‘hood have never used that term… When we’re talking about these places, there is so much life and vibrancy and potential. Using that word runs the risk of preventing us from seeing all of those things.”

Students harvest vegetables from a school garden. State Farm via Flickr

Second, by using the term “desert” one is implying that food deserts are naturally occurring. Deserts are classified by amount of precipitation an area receives, so they are dictated by weather patterns — forces beyond human control. Though increasing desertification due to climate change is exacerbated by human activities, for the most part, deserts are naturally occurring. Food deserts, in contrast, are not naturally occurring. They are the result of systematic racism and oppression in the form of zoning codes, lending practices, and other discriminatory policies rooted in white supremacy. Using the term desert implies that the lack of healthy and affordable food is somehow naturally occurring and obscures that it is the direct result of racially discriminatory policies and systematic disinvestment in these communities.

Building more grocery stores won’t necessarily make things better. Sometimes grocery stores are unaffordable to their surrounding communities. Sociologists have started using the term “food mirage” to describe the phenomenon when there are places to buy food, but they are too expensive for the neighborhood. And, as Karen Washington and research from Johns Hopkins University highlight, people who live in the places labeled “food deserts” most of the time do have food, but often the food they can afford is fast food or junk food. People who work in public health have come up with another term for areas with easier access to fast food and junk food than to healthier food: “food swamps.” Rather than simply building grocery stores, some of these communities need stable jobs and a livable wage to change their access to healthier food.

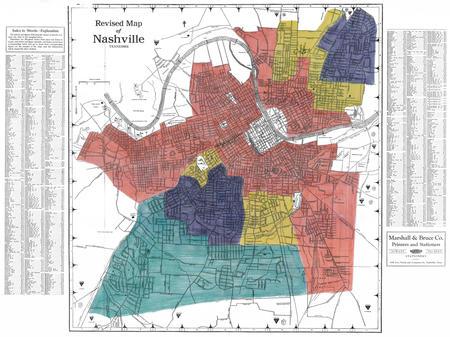

A Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) redlining map from the 1930’s that labeled “hazardous” majority Black areas of Nashville, Tennessee in red. HOLC

Swamp, desert, mirage… all these sound like places to stay away from. Language is important and using these terms prevents us from naming and addressing the root causes and making systemic change. Many groups are now using the term “food apartheid” to correctly highlight the how racist policies shaped these areas and led to limited access to healthy food. Apartheid is a system of institutional racial segregation and discrimination, and these areas are food apartheids because they too are created by racially discriminatory policies. Using the term “apartheid” focuses our examination on the intersectional root causes that created low-income and low food access areas, and importantly, points us towards working for structural change to address these root causes.

Corona Farmers Market, Queens, New York City. Preston Keres / USDA

Getting at the root causes is not a small task — naming them is the first step, and there are many different routes to take from there. Fortunately, there are many organizations already working on different aspects of addressing food apartheid, from building alternative food system models to providing ideas for policy reform. Organizations like The Ron Finley Project, the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network, and Whitelock Community Farm are strengthening regional food systems through urban and small-scale farming. SÜPRMARKT, Mandela Grocery, and other nonprofits are creating affordable, organic grocery stores, and re-thinking the grocery store model through co-ops. HEAL Food Alliance offers a comprehensive policy platform to address food apartheid root causes and build a better food system. As an example of transformative policy change, the Navajo Nation passed a tax on unhealthy food to fund community health initiatives in 2014. Ultimately, strong policies are necessary to ensure that no neighborhood experiences food apartheid and to redistribute power to remove systems of oppression.

A major component of power is economic capital — a reparations map maintained by Soul Fire Farm offers an easy way to start supporting efforts across the U.S. to more fairly allocate land and money and work toward repairing historical inequities based on race. In addition to economic capital, power is also control over your decisions and the choices you make. To address this, movements of food sovereignty seek to bring power back to the people. The Declaration of Nyéléni asserts that food sovereignty is the right of all people to design and influence their own food systems and the right to healthy, culturally appropriate, and sustainably-produced food.

The food sovereignty movement and the phrase “food sovereignty” were created by La Via Campesina, the largest international peasant movement. The term and movement have since expanded across the globe and into urban areas. I have encountered the term used to describe urban farming in large cities, like Baltimore, and to describe indigenous peoples reclaiming their native foodways. I have also heard people question if food sovereignty is the right term to cover these vast topics. I believe the words we choose help us see the way forward and if we are serious about transformative change, we should explore food sovereignty seriously.

In a similar way that using the term “food apartheid” can help us identify and address the root causes of the geographies that lack access to healthy food, highlighting “food sovereignty” as a call to action directly addresses the power dynamics at play in the food system. This term focuses the lens on how our modern, globalized food system does not value the rights of peasant and small-scale farmers anywhere and how in most cases the major decisionmakers are multinational corporations. The organization A Growing Culture says “there is no genuine food security without food sovereignty.” They continue, “We must stop seeing food security as the pathway to eradicating hunger. It reduces food to an economic commodity, when food is the basis of culture, of life itself. Food sovereignty is the pathway to imagining something fundamentally different.”

As we look forward and imagine a fundamentally different system that nourishes all people and the planet, we have a wealth of knowledge and examples to draw upon, as well as rich terminology to describe the challenges communities are facing and our goals for the future. Any efforts to achieve — and ways we discuss — a better, more equitable, food system should address root causes, redistribute power, and be guided by people with lived experience in food apartheids. Food security is more than proximity to a grocery store; it should be about food sovereignty — the right of all people to have a say in how their food is grown and the right to fresh, affordable, and culturally appropriate food.

Reposted with permission from Natural Resources Defense Council.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe