It's OK, I'm a filter feeder: Whale shark off Indonesia. Marcel Ekkel, /Flickr / CC BY

By Gavin Naylor

Sharks elicit outsized fear, even though the risk of a shark bite is infinitesimally small. As a marine biologist and director of the Florida Program for Shark Research, I oversee the International Shark Attack File — a global record of reported shark bites that has been maintained continuously since 1958.

We are careful to emphasize how rare shark bites are: You are 30 times more likely to be struck by lightning than be bitten by a shark. You are more likely to die while taking a selfie, or be bitten by a New Yorker. In anticipation of the anxiety that’s typically generated by the Discovery Channel’s Shark Week programming, here are a few things about sharks that are often overlooked.

A Big, Diverse Family

Not all sharks are the same. Only a dozen or so of the roughly 520 shark species pose any risk to people. Even the three species that account for almost all shark bite fatalities — the white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) and bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas) — are behaviorally and evolutionarily very different from one another.

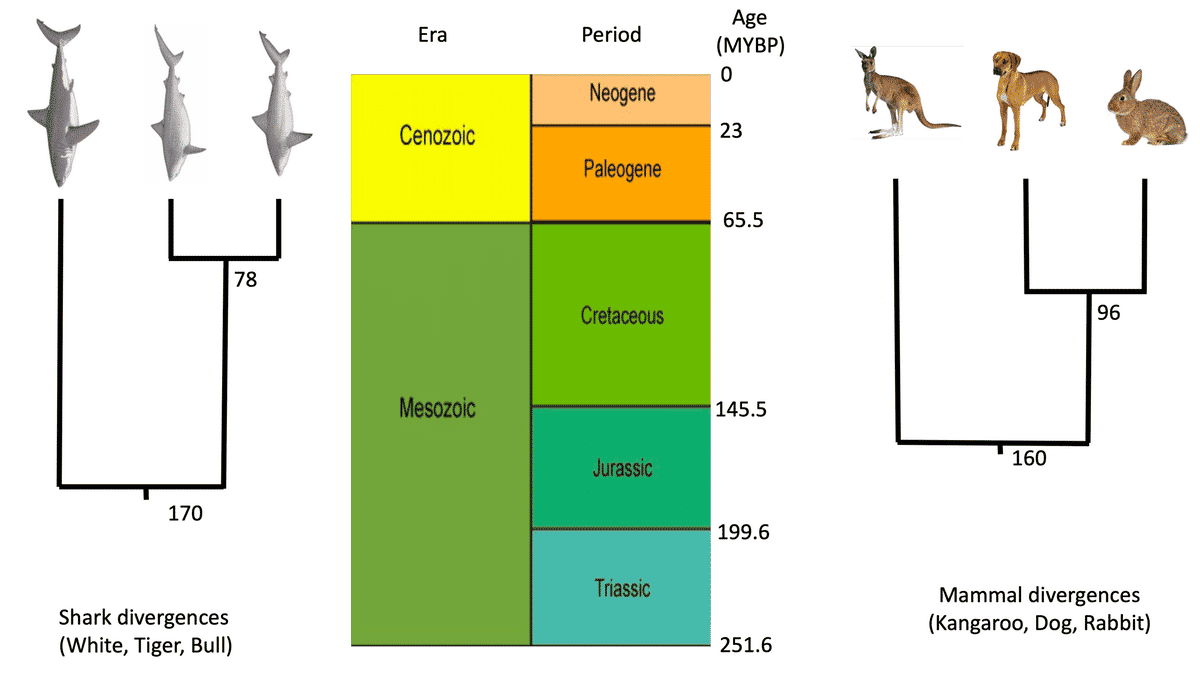

The tiger shark and bull shark are genetically as different from each other as a dog is from a rabbit. And both of these species are about as different from a white shark as a dog is from a kangaroo. The evolutionary lineages leading to the two groups split 170 million years ago, during the age of dinosaurs and before the origin of birds, and 110 million years before the origin of primates.

Yet many people assume all sharks are alike and equally likely to bite humans. Consider the term “shark attack,” which is scientifically equivalent to “mammal attack.” Nobody would equate dog bites with hamster bites, but this is exactly what we do when it comes to sharks.

So, when a reporter calls me about a fatality caused by a white shark off Cape Cod and asks my advice for beachgoers in North Carolina, it’s essentially like asking, “A man was killed by a dog on Cape Cod. What precautions should people take when dealing with kangaroos in North Carolina?”

Know Your Species

Understanding local species’ behavior and life habits is one of the best ways to stay safe. For example, almost all shark bites that occur off Cape Cod are by white sharks, which are a large, primarily cold-water species that spend most of their time in isolation feeding on fishes. But they also aggregate near seal colonies that provide a reliable food source at certain times of the year.

Shark bites in the Carolinas are by warm-water species like bull sharks, tiger sharks and blacktips (Carcharhinus limbatus). Each species is associated with particular habitats and dietary preferences.

Blacktips, which we suspect are responsible for most relatively minor bites on humans in the southeastern U.S., feed on schooling bait fishes like menhaden. In contrast, bull sharks are equally at home in fresh water and salt water, and are often found near estuaries. Their bites are more severe than those of blacktips, as they are larger, more powerful, bolder and more tenacious. Several fatalities have been ascribed to bull sharks.

Tiger sharks are also large, and are responsible for a significant fraction of fatalities, particularly off the coast of volcanic islands like Hawaii and Reunion. They are tropical animals that often venture into shallow water frequented by swimmers and surfers.

Humans Are Not Targets

Sharks do not “hunt” humans. Data from the International Shark Attack File compiled over the past 60 years show a tight association between shark bites and the number of people in the water. In other words, shark bites are a simple function of the probability of encountering a shark.

This underscores the fact that shark bites are almost always cases of mistaken identity. If sharks actively hunted people, there would be many more bites, since humans make very easy targets when they swim in sharks’ natural habitats.

Local conditions can also affect the risk of an attack. Encounters are more likely when sharks venture closer to shore, into areas where people are swimming. They may do this because they are following bait fishes or seals upon which they prey.

This means we can use environmental variables such as temperature, tide or weather conditions to better predict movement of bait fish toward the shoreline, which in turn will predict the presence of sharks. Over the next few years, the Florida Program for Shark Research will work with colleagues at other universities to monitor onshore and offshore movements of tagged sharks and their association with environmental variables so that we can improve our understanding of what conditions bring sharks close to shore.

More to Know

There still is much to learn about sharks, especially the 500 or so species that have never been implicated in a bite on humans. One example is the tiny deep sea pocket shark, which has a strange pouch behind its pectoral fins.

Only two specimens of this type of shark have ever been caught — one off the coast of Chile 30 years ago, and another more recently in the Gulf of Mexico. We’re not sure about the function of the pouch, but suspect it stores luminous fluid that is released to distract would-be predators — much as its close relative, the tail light shark, releases luminous fluid from a gland on its underside near its vent.

Sharks range in form from the bizarre goblin shark (Mitsukurina owstoni), most commonly encountered in Japan, to the gentle filter-feeding whale shark (Rhincodon typus). Although whale sharks are the largest fishes in the world, we have yet to locate their nursery grounds, which are likely teeming with thousands of foot-long pups. Some deepwater sharks are primarily known from submersibles, such as the giant sixgill shark, which feeds mainly on carrion but probably also preys on other animals in the deep sea.

Sharks seem familiar to almost all of us, but we know precious little about them. Our current understanding of their biology barely scratches the surface. The little we do know suggests they are profoundly different from other vertebrate animals. They’ve had 400 million years of independent evolution to adapt to their environments, and it’s reasonable to expect they may be hiding more than a few tricks up their gills.

Gavin Naylor is the director of the Florida Program for Shark Research at the University of Florida.

Disclosure statement: Gavin Naylor receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the Lenfest Ocean Program.

Reposted with permission from our media associate The Conversation.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe