Researchers have discovered that bottlenose dolphins residing off the Florida Everglades have higher concentrations of mercury contamination than any other population of the mammals in the world.

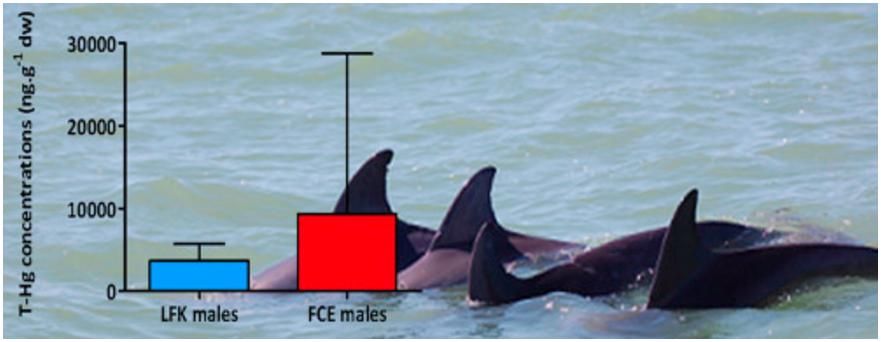

The study, published in the journal Environmental Pollution, examined the levels of mercury and other toxins in the sea creatures. According to the research, mercury concentrations in the skin of Florida Coastal Everglades dolphins (median 9314 ng g−1 dw) were about three times higher than Lower Florida Keys dolphins (median 2941 ng g−1 dw).

“These concentrations are the highest recorded in bottlenose dolphins in the southeastern USA, and may be explained, at least partially, by the biogeochemistry of the Everglades and mangrove sedimentary habitats that create favorable conditions for the retention of mercury and make it available at high concentrations for aquatic predators,” the study abstract states.

The research team includes scientists from Florida International University (FIU), the University of Liège in Belgium, the University of Gronigen in the Netherlands and the Tropical Dolphin Research Foundation in the U.S.

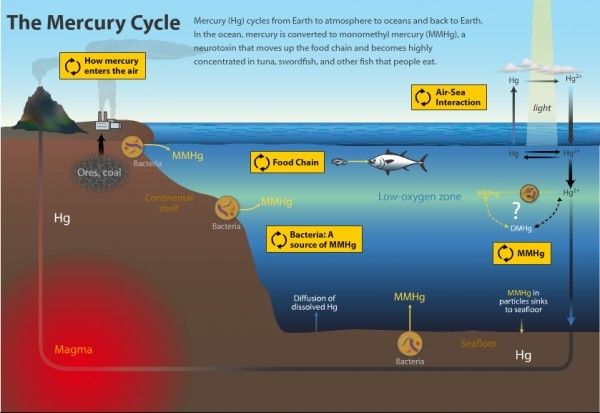

It is unclear where exactly the mercury comes from but the scientists suspect it might stem from smoke stacks, nearby farming operations or from the area’s numerous mangroves in Everglades National Park. As FIU News explained, when mangrove leaves drop into the water, mercury from the mangroves mixes with bacteria and is turned into methylmercury. Methylmercury is highly toxic and can travel up the food chain, as it collects in animal tissue in larger and larger amounts. (That’s why predators like dolphins, swordfish and tuna have troubling levels of mercury.)

Dolphins that live in the Amazon and other mangrove forests also have elevated mercury levels, but the researchers were surprised to find that the mercury levels in Everglades dolphins were even higher.

“I couldn’t believe those levels because that’s the highest ever recorded,” FIU marine scientist Jeremy Kiszka, a co-author of the study, told the Miami Herald. “It raises a lot of other questions.”

The study is important because dolphins are a vital “sentinel species,” meaning they shed light on oceanic and human health. So if a dolphin is swimming in contaminated waters, a person living by the same coastal waters might also be exposed to the same contamination. As the Miami Herald noted, researchers discovered last year that Indian River Lagoon dolphins had elevated mercury levels, reflecting the high levels of mercury in the nearby human population.

News story on our work on #mercury levels in #everglades #dolphins https://t.co/iyInMFQejF @fiuseas @fcelter @jjkiszka

— Mike Heithaus (@MikeHeithaus) December 1, 2016

Similarly, since dolphins and humans eat the same kind of seafood, if a dolphin gets sick from eating toxic fish, a person who eats the same toxic fish might get sick too.

For humans, mercury can have a whole host of terrifying problems. As for what effects mercury has on dolphins, FIU News explained that the chemical can disrupt the animal’s immune system and reproduction, making them more vulnerable to infection and disease.

“Mercury is one of the most neurotoxic elements in the universe,” World Mercury Project president Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., who was not involved in the study, explained to EcoWatch. “The destruction of these extraordinary creatures is part of the cost of our deadly addiction to coal and chemicals. We shouldn’t forget that these dolphins are accumulating these horrifying brain poisons from the same fish that our children eat.”

Burning Less Coal = 19% Less Mercury in the Tuna You Eat https://t.co/WTb3JGAJXC @WorldMercury @RobertKennedyJr @CarlPope @ewg @CleanAirMoms

— EcoWatch (@EcoWatch) November 25, 2016

The scientists are now trying to expand their study on other marine animals.

“Understanding the impact of pollutants on marine ecosystems, including from natural sources, is critical for conservation and management. Results obtained on bottlenose dolphins from the Everglades were surprising, but we now need to assess the effect of mercury on the health of dolphins and other species from the Everglades,” Kiszka told FIU News. “This is a critical question for understanding the effects of pollutants on aquatic ecosystems, but also on humans, since we are also part of these ecosystems.”

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe