ESA CHEOPS Mission Launches to Study Evolution of Planets Orbiting Nearby Suns

A Soyouz rocket lift-off from Europe's launchpad in Kourou, French Guiana, on Dec. 18 with Europe's CHEOPS planet-hunting satellite on board. JODY AMIET / AFP / Getty Images

By Matthias Klaus

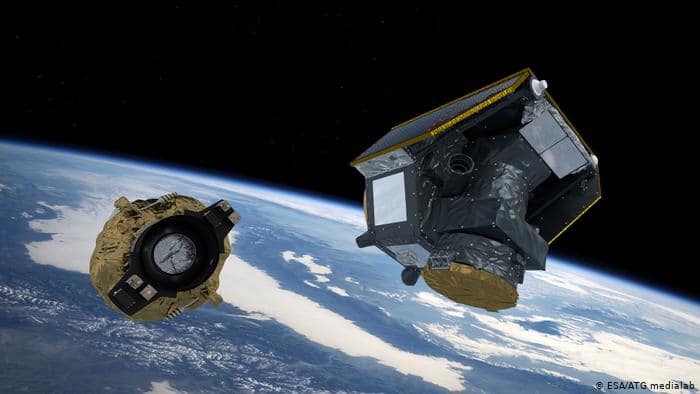

The CHEOPS mission blasted off from Kourou, French Guiana atop a Russian Soyuz rocket on Wednesday. The launch came 24 hours after a first attempt was delayed shortly before liftoff because of a software problem in the upper stage of the rocket.

Scientists have long theorized with near certainty that there are countless planets in the universe, given the sheer numbers of stars. But it has only been possible to truly prove this since the 1990s.

Since then, thousands of so-called exoplanets, i.e. planets outside our solar system, have been discovered. As of yet, we don’t know what these planets consist of or whether they have atmospheres.

That’s why the CHEOPS mission of the European Space Agency (ESA) is preparing to investigate some of the known exoplanets in more detail.

Measuring the Light Intensity of Stars

CHEOPS stands for “CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite,” a satellite for the exploration of exoplanets. Despite the fact that exoplanets are incredibly far away from us (far outside our solar system, orbiting around distant stars), the mission is actually not that expensive.

“CHEOPS is a small mission in terms of scope, cost and also in terms of the time it takes to develop the mission,” says Kate Isaak, a scientific coordinator of CHEOPS. “The mission is to measure the size of planets orbiting nearby suns.”

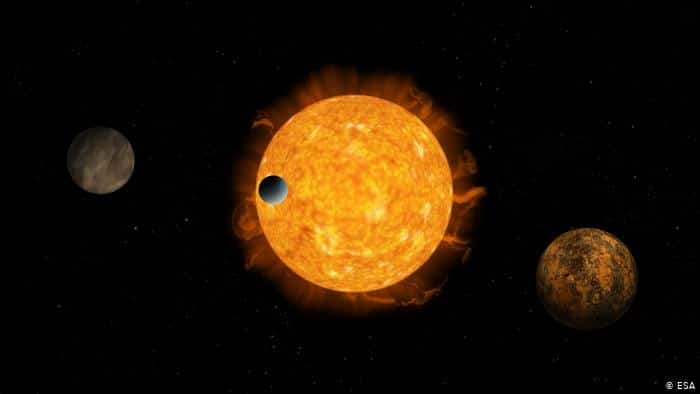

And this is how it works: when a planet passes a star on its orbit, the star’s light becomes darker for a short time. This is like a small solar eclipse that can be observed by CHEOPS.

And even if the same planet is placed behind the star from the point of the observer, it reflects the light of the star back. CHEOPS can still see that, too. Astronomers can compute the size of the planet from the attenuation of the light. And the light reflections emitted by the planet itself provide clues as to whether, for example, it has an atmosphere.

A Closer Look at Known Exoplanets

“By combining the size of the planets with their mass, something we can measure with telescopes on Earth, we learn a lot about the composition of the planets and their evolution,” says Isaak.

All these differences are, of course, very small, since the stars and planets observed are several light years away. In order to be able to measure them at all, any disturbance must be excluded.

That’s the reason why such observations are best made using space-based telescopes rather than those on Earth. The Earth’s atmosphere would simply get in the way. CHEOPS is designed to target planets that are larger than Earth and smaller than Neptune.

Will CHEOPS Find Aliens?

The mission will take three and a half years. But, this time, the question of all questions will not be answered.

“The question of whether we are alone in the universe is certainly one of the most fundamental questions ever,” says Isaak. But CHEOPS will not get that far. “Other satellites have shown that there are planets beyond our solar system. So it is clear that there are exoplanets. What we want to show now is what these smaller rock planets are like and how they evolve.”

After all, it should be possible to identify at least some planets on which extraterrestrial life is at least conceivable.

“What we are looking for now are the best planetary candidates for future exploration by other satellites such as the James Webb Space Telescope or by observatories [such as the European Southern Observatory (ESO)] in South America. From there, we can study the atmospheres of these candidates and search for molecules characteristic of the presence of life.”

Modular Research Satellite Design

In addition to the scientific findings that the CHEOPS mission will provide, the ESA looking for ways of making research satellites cheaper. The satellite developers have come up with new technologies for this purpose.

“Satellites are very expensive and very complex to build. And these programs always take a very long time,” says Richard Southworth of the European Space Operations Centre (ESOC). He is responsible for controlling the CHEOPS satellite.

“With CHEOPS, the idea was to see if we could do it better, a little faster and less costly. We have tried to keep the probe relatively simple and above all to use parts that have flown on other missions before. These components will then be less expensive and more reliable because they have already been tested.”

ESA also saves on the transport of the probe into space: CHEOPS flies on a Soyuz rocket as cargo. So the project shares the travel costs with another — in this case an Italian — satellite.

And even if the satellite is already in the sky, there is still an opportunity to reduce costs. The CHEOPS researchers use the flying telescope only 80 percent of the time. The rest of the time others can rent it for their own research.

Scrapping Already Firmly Scheduled

The research itself will then begin after a test period of several months. But what happens to CHEOPS when the project is finished?

“It’s planned to operate for three and a half years,” says satellite controller Southworth. “But the design of the satellite should ensure that we could also fly for five years if there is money and interest. In the end, we deactivate the satellite and initiate de-orbiting.”

The satellite will first be switched into a passive mode so that it can no longer interfere with radio signals or other satellites.

“Finally, we will also make an orbit correction. This will lead to the satellite’s safe return to Earth. That means CHEOPS won’t become space debris in the long run.”

In the end, the probe will burn and disintegrate when entering the earth’s atmosphere.

Reposted with permission from Deutsche Welle.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe