Indiana Harbor in East Chicago, Indiana. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Chicago District

By Gloria Oladipo

Akeeshea Daniels once lived in the West Calumet public housing complex in the shadow of a former lead smelter in East Chicago, Indiana. She worried about the pervasive lead contamination in the area and hoped that the government would fix the problem. Officials tried — and are still trying — to clean up the mess, but in many ways their efforts have made life harder for residents like Daniels.

After letting industrial pollution linger for decades, in 2016, city and federal officials forced residents of the housing complex to move — but they neglected to provide them adequate means to find new homes. Residents continued to pay rent at the contaminated complex even as they searched for housing elsewhere. Some ended up homeless or relocating to neighborhoods mired in violence.

Daniels struggled to find somewhere she could afford. Every time she had applied to a new apartment, the landlord would run a credit check. The repeated credit checks put a dent in her credit score. “A lot of our credit scores took a hit after they were run at least 19 times total,” she said. “Nobody ever said anything about trying to help us build our credit back up.” Her lower credit score made it difficult to secure a lease.

When she finally did find a place, she left everything behind from her former apartment because she was afraid of bringing lead-tainted furniture to her new home. “A lot of us walked away with nothing,” she said. “I had to start over. No beds, no dressers, no nothing.”

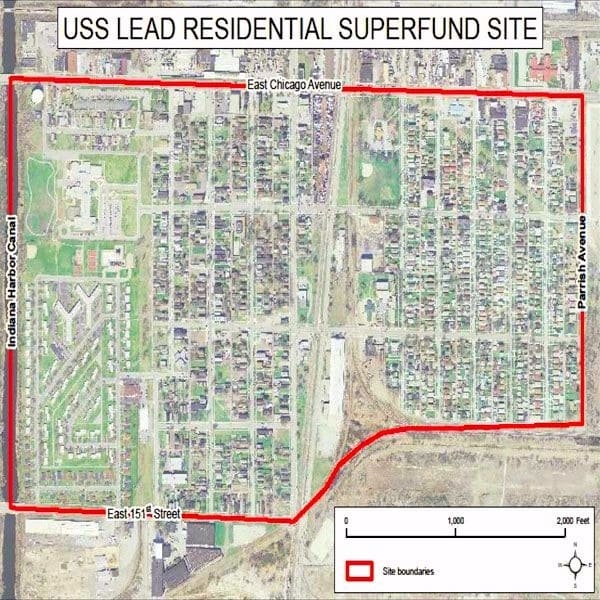

The USS Lead Superfund site.

Source: Environmental Protection Agency

The contamination is nothing new. In 1985, the Indiana State Department of Health discovered lead contamination near the USS Lead facility, the same year the facility closed down. While USS Lead would later clean up lead waste at the facility, contamination would linger in the surrounding areas. It wasn’t until 2009 that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) added parts of the USS Lead facility and the surrounding neighborhood to the Superfund National Priorities List.

“Growing up, you heard the folktales that we were living on top of lead, but I never knew. I never did any research and I was never told by the complex,” Daniels said.

In the summer of 2016, the EPA sent letters to residents of the housing complex informing them of the lead contamination. Frustrated by the slow pace of the EPA cleanup effort, which continues to this day, East Chicago Mayor Anthony Copeland called on the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to demolish the West Calumet Housing Complex, which it did, forcing more than a thousand residents to move out.

Debbie Chizewer, a Montgomery Foundation Environmental Law Fellow at the Northwestern Pritzker School of Law, and one of the attorneys representing the East Chicago/Calumet Coalition Community Advisory Group, spoke about the difficulty relocating the West Calumet residents.

“One of the problems is that moving 348 families at once when there’s limited affordable housing and Section 8 housing [a federal program that provides rental assistance to low-income tenants] in East Chicago is almost impossible,” she said.”It was difficult to use the housing vouchers both because East Chicago doesn’t have enough housing, and in other communities, residents were being discriminated against.”

EPA workers collect soil samples.

Source: Environmental Protection Agency

Facing a lack of affordable housing, Daniels pursued Section 8 housing using vouchers provided by the East Chicago Housing Authority, though she found it difficult to navigate the process.

Similarly, Thomas Frank, a co-founder of Calumet Lives Matter, which advocates for residents affected by lead contamination, said HUD gave residents little help relocating. “HUD basically sent [West Calumet residents] to the wind and sent them all over the country,” he said. Many residents, he added, “ended up losing their jobs, and several of them ended up homeless.” This is partly due to the fact that many residents “weren’t accepted into the [public housing] they were assigned.” Frank described one woman who was homeless for six weeks before being accepted back into East Chicago public housing — only to be relocated again.

Kate Walz, vice president of advocacy and senior director of litigation at the Shriver Center, pushed HUD to ensure residents had adequate time and money to relocate. She spoke about the issues residents faced when finding new landlords.

“The housing authority gave out the same list of landlords to all of the families who were moving,” she said. “People were essentially competing against each other.” She noted that some of the properties landlords had listed had no available units, while others offered only apartments that were in poor shape.

Many East Chicago residents could not afford to move, as they were unable to cover the cost of housing application fees, background checks and other moving expenses. And, while finding somewhere new to live, residents were still expected to pay rent for apartments on contaminated land. “I paid my rent until I left,” Daniels said. “They decided they weren’t going to give that money back to us.”

EPA staff speak to residents of the Superfund site.

Source: Environmental Protection Agency

Once they moved, many former residents had problems adjusting to their new environments. “The only other place [West Calumet residents] could move is what’s called ‘The Harbor,'” Frank said, a neighborhood where locals have a history of conflict with West Calumet residents. “When East Chicago HUD started moving residents into ‘The Harbor,'” he said, “lots of violence occurred.”

Daniels is worried that she won’t be able to afford to move again if needed. HUD paid for the security deposit for a new home, but should she ever move, HUD will recover that deposit, meaning she will have to come up with the money for a future security deposit.

Daniels also noted that HUD’s file on her and her family contains sensitive information like their social security numbers. She worries that some of that information might have gotten misplaced. When she received her file during the move, she said she discovered “at least 30 pages” of other peoples’ information.

After all the tumult and hardship, Daniels and her children are still living in a home on the Superfund site, just not in the West Calumet housing complex. “The inside of the house has never been tested,” she said. “The water also hasn’t been tested, so I still don’t know what I’m exposing myself and my children to.”

Private homeowners on the Superfund site were left to fend for themselves. “We didn’t get anything, honestly, for moving expenses or any kind of compensation at all,” said Sara Jimenez, who lived near the old lead smelter. Eager to move, but unable to sell their home, Jimenez and her husband are renting to a woman who was willing to move in despite the lead contamination. “We told her [about the pollution],” Jimenez said. “I said, ‘Do you really want to rent this place?'”

They dug into their retirement to secure a new home, but they still miss their old neighborhood. “[My husband and I loved] our house there,” she said. “We lived in a real nice community where everybody knew each other.” She added, “Our plans were to stay there until we died.”

For Jimenez, Daniels and others threatened by lead contamination, the housing crisis has bred mistrust between residents and the EPA, companies that originally polluted the area, and the East Chicago government. Bureaucratic dysfunction left residents with nowhere to turn, and in some cases, nowhere to live. “They act like they’re going to do something,” Jimenez said. “They don’t.”

Reposted with permission from our media associate Nexus Media.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe