Deep-Sea Mining Threatens 62% of Hydrothermal Vent Molluscs With Extinction

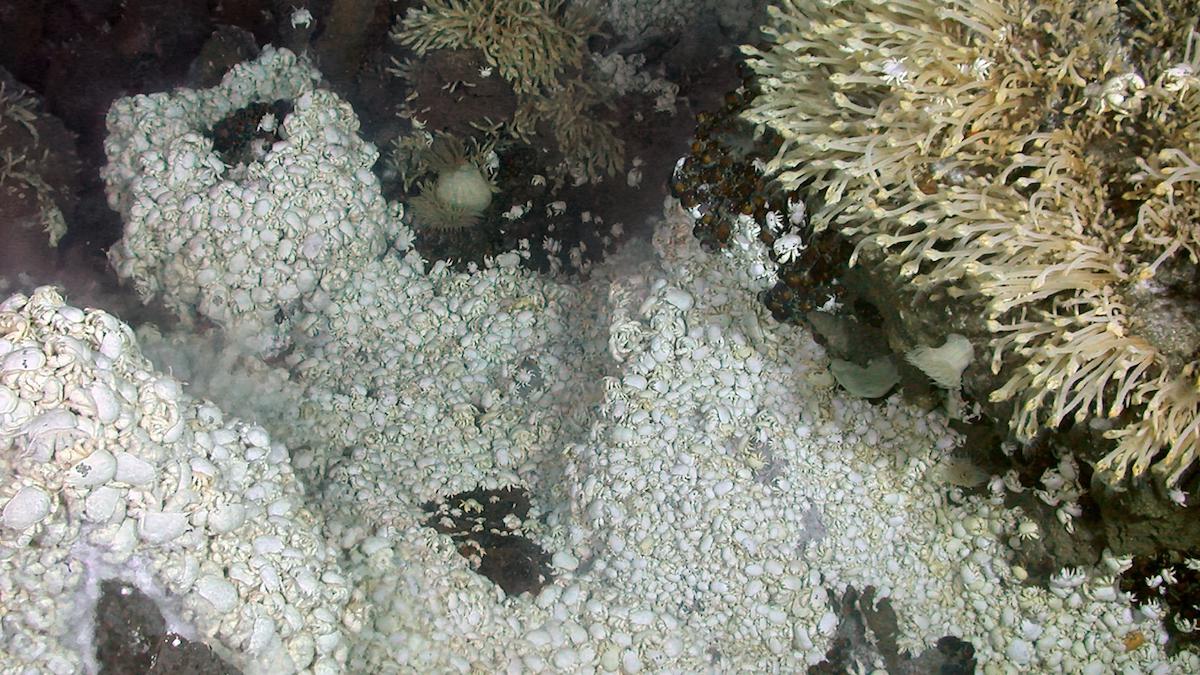

Hydrothermal vents have a biomass equivalent to tropical rainforests or coral reefs. A. D. Rogers et al. / CC BY 2.5

One of the major arguments against deep-sea mining is that it could do “irreversible damage” to the poorly understood ecosystems far below the waves.

Now, a new study published in Frontiers in Marine Science this month adds credence to this view. The research focused on 184 species of molluscs found only in hydrothermal vents, and found that 62 percent of them were listed as threatened according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, all because they lived in areas being considered for mining.

“Our study shows that mining regulation matters,” lead researcher and Queen’s University Belfast Ph.D. student Elin Thomas told EcoWatch in an email. “Species restricted to areas with mining contracts are assessed at the top end of the Red List, all the way up to Critically Endangered, whereas species found in areas that are protected by effective conservation strategies are assessed at the opposite end of the spectrum, as Least Concern.”

A Vent Red List for Molluscs

Deep-sea vents are the habitats at risk from deep-sea mining that have the highest density of life. In fact, their biomass rivals that of coral reefs or tropical rainforests. Further, they are fonts of unique biodiversity. Many species are endemic, or native, to only one vent site.

Molluscs are some of the most common and important species in vent habitats. To better understand the threats these species face, the international research team assessed 184 vent-specific mollusc species according to the criteria of the IUCN Red List to create a “Vent Red List for Molluscs.”

“The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species is an effective and well-recognized tool to promote the protection of species and presents an opportunity to communicate conservation threats to industry, policy makers, and the general public,” the study authors explained.

The Red List relies on a species’ geographic range and any current or future threats to rate a species’ conservation status along five escalating stages: Least Concern, Near Threatened, Vulnerable, Endangered and Critically Endangered.

Of the 184 species the researchers assessed, 39 are Critically Endangered, 32 are Endangered, 43 are Vulnerable, 45 are Near Threatened and 25 are Least Concern. The Least Concern species all live in areas that are fully protected from deep-sea mining, while the Near Threatened species have some populations at risk from mining and some in protected areas.

“This conveys the very real extinction risk that deep-sea mining poses to hydrothermal vent communities,” Thomas said, adding that “the study sets a precedent for the efficient use of conservation tools like the IUCN Red List to identify and communicate threats to other understudied deep-sea habitats and species.”

While the Red List has assessed more than 140,000 species, fewer than 15 percent of them come from marine environments and even fewer from the deep sea, according to a Queen’s University press release emailed to EcoWatch. The new study has added all 184 of the molluscs it assessed to the list.

The Mining Threat

Why is deep-sea mining such a threat to vent species like molluscs?

One deep-sea mining proposal is to mine seafloor massive sulfides from hydrothermal vents, according to a 2018 study also published in Frontiers in Marine Science. These sulfides are rich in copper, gold, zinc, lead, barium, and silver, but mining them from vents would mean removing vent chimneys entirely, which would make it very difficult for habitat and species to recover. Mining could further harm vent species by causing noise and light pollution, crushing them with heavy machinery, leaving physical waste and introducing new species that could compete with the vent species for resources.

The mollusc research in particular was inspired by a research trip Thomas’s supervisor took to vents in the Indian Ocean. The vent species in this region are at the greatest risk from deep-sea mining. Because of contracts granted there by the International Seabed Authority, 100 percent of vent molluscs in the region are threatened with extinction and 62 percent are Critically Endangered.

An example of an individual species under threat is the Dragon Snail (Dracogyra subfusca). This species is newly discovered, yet already listed as Critically Endangered because it only lives in one hydrothermal vent that is under an exploratory mining contract from the International Seabed Authority.

“The Dragon Snail is also the only known member of the genus Dracogyra so there is a chance the entire group could go extinct, and sadly, there are many more examples like this, of deep-sea species that are so new to us and yet are facing such significant threats,” Thomas said.

The lack of scientific knowledge about the deep ocean combined with the risks posed by deep-sea mining is a major reason that more than 622 marine science and policy experts have signed a statement calling for a moratorium on the practice until more is known about its true impacts. This is a goal that Thomas supports.

“Our findings support a precautionary approach for deep-sea conservation, including the implementation of a deep-sea mining moratorium, which is essential to allow for further research into the biodiversity, ecology, connectivity, and resilience of these rich animal communities,” Thomas said.

She also plans to contribute to this further research.

“Hydrothermal vents aren’t even the only target of the deep-sea mining industry and applying the IUCN Red List criteria to the species found in these other areas could be a big step forward for their conservation,” she said.

- Deep-Sea Study Records Species Found Nowhere Else on Earth ...

- Race to Mine Deep Seabeds, With Unknown Ecological Impacts ...

- David Attenborough Calls For Ban on Deep-Sea Mining - EcoWatch

- Major Companies Join Call for Deep-Sea Mining Moratorium ...

- Deep-Sea Mining Not Necessary for Renewable Energy Transition ...

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe