New Film ‘Dark Waters’ Shines Light on Chemical Pollution History in Ohio River Valley

Mark Ruffalo, right, playing attorney Rob Bilott in the film Dark Waters. Credit: Dark Waters

By Sharon Kelly

Dark Waters, the new film starring Mark Ruffalo as attorney Rob Bilott, is set in the Ohio River Valley city of Parkersburg, West Virginia — a place about 150 miles downstream from where Shell is currently building a sprawling plastics manufacturing plant, known as an “ethane cracker,” in Beaver, Pennsylvania.

Ruffalo’s film, directed by Todd Haynes, debuted to critical acclaim, earning a Rotten Tomatoes critics’ rating of 91 percent, with The Atlantic calling it a “chilling true story of corporate indifference.”

While much of Dark Waters, as the title suggests, centers on contaminated water, the story of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), the Teflon-linked chemical at the heart of the film, is also a story about air pollution. And as much as the film looks back to history, DuPont’s pollution — and the company’s decades-long cover-up — may gain new relevance as the chemical industry plans a multi-billion dollar expansion, fed by fracked fossil fuels, along the banks of the Ohio.

The film begins as a detective story set in the 1990s, as Bilott, a corporate defense attorney, begins investigating the bizarre deaths of cattle in a farming region he’d visited as a child. Bilott discovers the chemical culprit’s identity less than an hour into the 2 hour and 7 minute film — and then spends the remainder of the movie pitting his personal tenacity against the DuPont corporation’s deep-pocketed endurance, as even partners at Bilott’s own law firm question his work.

The movie highlights DuPont’s legal maneuvering, showing the company seeking to evade liability by “notifying” customers that the chemical was in their water at levels the notice suggested were “safe” — starting a time clock running for the statute of limitations on DuPont’s liability.

The film’s extended runtime mirrors the duration of Bilott’s real-life legal battles with DuPont, which began as a single civil suit on behalf of farmer Wilbur Tennant but gradually expanded to become one of the largest medical monitoring lawsuits in U.S. history. Real impacted people, including Bucky Bailey and Parkersburg elementary school teacher Joe Kiger and his wife, appear on screen along Ruffalo, Anne Hathaway and Tim Robbins, playing themselves in roles that layer an aura of realism onto the tale.

A Chemical History

Beyond the Ohio River Valley, PFOA, which according to a 2016 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency fact sheet, can cause cancer, harm to fetuses, immune system issues and other health problems, has spread rapidly around the world.

First developed in the lab less than a century ago, PFOA can now be found in the bloodstreams of an estimated 99.7 percent of Americans, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and in wildlife ranging from polar bears to dolphins to bald eagles. Once released, PFOA and the hundreds of other PFAS chemicals like it may take millennia to break down. Tied together by one of nature’s strongest known chemical bonds, the carbon-fluorine bond, the molecule doesn’t naturally degrade from exposure to light or water to break down over time. Instead, it bioaccumulates in the bloodstream, building up and exposing those higher up the food chain to progressively higher levels of the chemical.

Bilott’s class action lawsuit centers on the water contamination from PFOA, which DuPont started using to produce its nonstick coating Teflon at its Parkersburg plant in 1951. His plaintiffs were customers of six water districts along the Ohio River on both the West Virginia and Ohio sides of its banks.

But while DuPont buried drums of the PFOA waste on the banks of the Ohio and otherwise disposed of its waste — in part, long before the nation’s cornerstone environmental laws were written — PFOA itself is also a powdery dust that readily becomes airborne — and the Ohio River is lined on both sides by tall hills that can at times trap air pollution in the valley, where coal and steel towns dot the riverbanks.

Documents obtained by Bilott’s legal team show DuPont slowly realized the dangers that the mix of air pollution and steep hills posed to the surrounding communities. In fact, one DuPont lawyer later privately bemoaned the fact that the company, which had been secretly testing the water for decades, hadn’t checked for PFOA in the air.

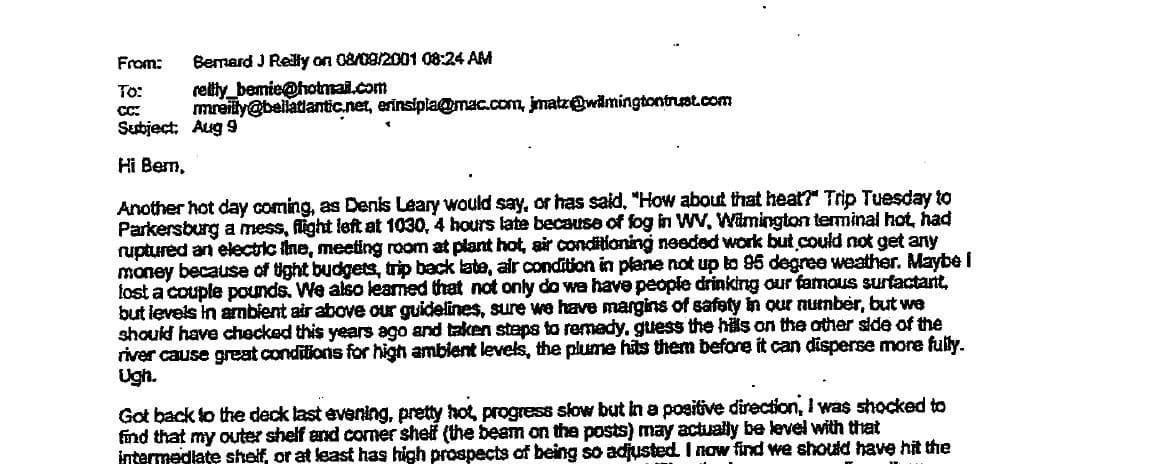

“We also learned that not only do we have people drinking our famous surfactant (PFOA), but levels in ambient air above our guidelines, sure we have margins of safety in our number, but we should have checked this years ago and taken steps to remedy, guess the hills on the other side of the river cause great conditions for high ambient levels, the plume hits them before it can disperse more fully,” DuPont attorney Bernard Reilly wrote in an August 9, 2001 email. “Ugh.”

Email that DuPont attorney Bernard Reilly wrote on Aug. 9, 2001.

PFOA’s ability to become airborne may have helped it spread to some of the furthest reaches of the globe.

“The state of North Carolina has demonstrated atmospheric deposition of PFAS many miles downwind from a manufacturing facility,” the Michigan Department of Environment said in a Q&A on the chemicals. “New Hampshire found contaminated groundwater was caused by atmospheric deposition of PFAS from industrial emissions of PFAS. Additionally, PFAS have been sampled and found in remote regions such as the Arctic.”

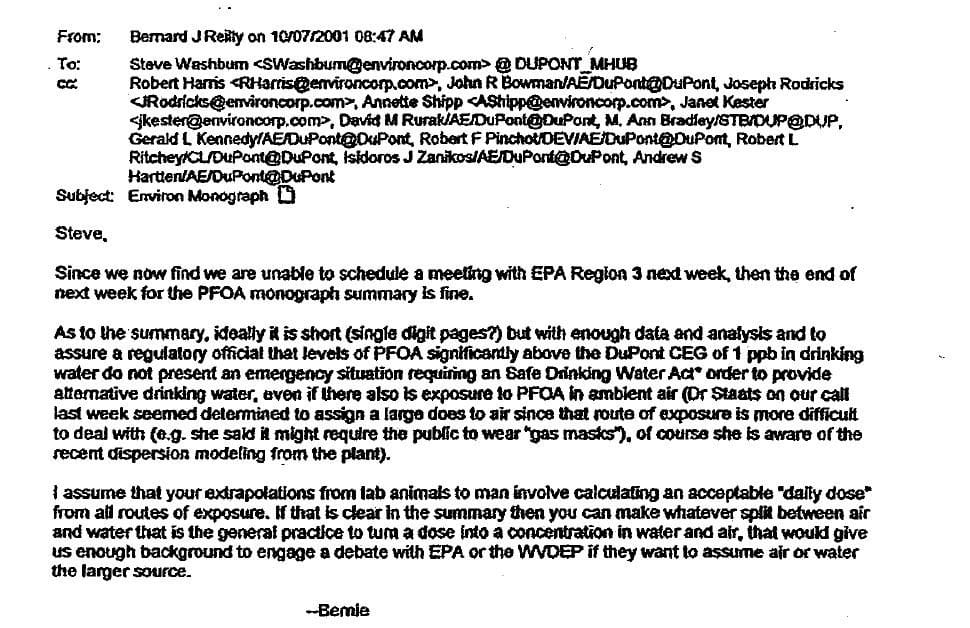

In 2001, DuPont’s attorney wrote that one scientist was so concerned about the PFOA air pollution in the valley that she suggested residents should wear masks. “Dr. Staats on our call last week seemed determined to assign a large does [sic] to air since that route of exposure is more difficult to deal with (e.g. she said it might require the public to wear ‘gas masks’), of course she is aware of the recent dispersion modeling from the plant,” Reilly wrote on Oct. 7 of that year.

Email that DuPont attorney Bernard Reilly wrote on Oct. 7, 2001.

DuPont also worked hard to pressure state environmental regulators to move slowly in response to the harms from PFOA — not because the dangers weren’t real, but because the air pollution in the valley hadn’t been accounted for.

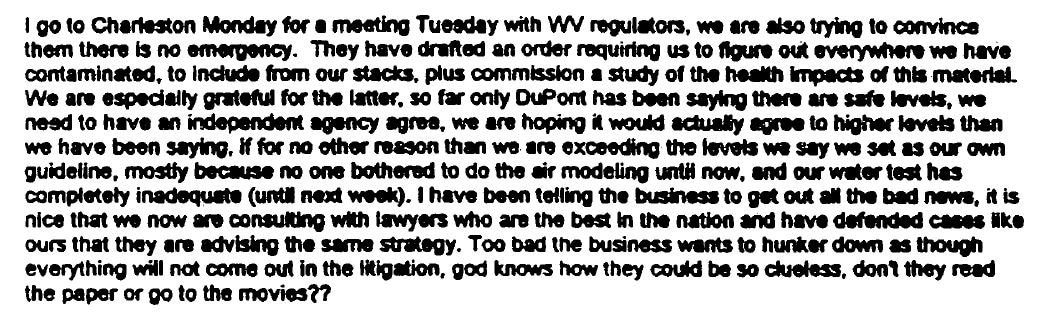

“I go to Charleston Monday for a meeting Tuesday with WV regulators, we are also trying to convince them there is no emergency,” Reilly wrote in an Oct. 13, 2001 email. “… [W]e are hoping [an independent agency] would actually agree to higher levels than we have been saying, if for no reason than we are exceeding the levels we say we set as our own guideline, mostly because no one bothered to do the air modeling until now, and our water test has been completely inadequate (until next week).”

Email that DuPont attorney Bernard Reilly wrote on Oct. 13, 2001.

Chemical Lessons for the Future

With an expanding petrochemical industry eyeing the Ohio as the site for tens of billions of dollars’ worth of new petrochemical and plastic production, some in Parkersburg are wary of the environmental — and political — lessons from PFOA. Ohio and West Virginia have been slower than other states to respond to the pollution, reporter Nicholas Brumfield wrote in a piece published by expatalachians.

“For Parkersburg’s Eric Engle, this inaction [on regulating PFAS in West Virginia and Ohio] is linked to the powerful influence of local petrochemical industries,” Brumfield wrote. “‘We have politicians still investing in petrochemicals to save the oil and gas industry … They’re wanting to store ethane here now. We’re still learning about the dangers of all these petrochemicals … We have to move past it,’ Engle said.

It’s worth observing that DuPont’s PFOA pollution began long before today’s federal environmental laws were written, like the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act and the Safe Drinking Water Act. Nonetheless, some in the Ohio River Valley remain concerned about the impacts that permitted pollution from new petrochemical projects could have.

“As I sat and watched the newly released movie Dark Waters, I thought, ‘This could be the future of the Ohio River Valley,'” Randi Pokladnik, a retired research chemist who volunteers for the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition, wrote in a Dec. 13 letter to the editor published by the Columbus Dispatch. “Ohio’s regulatory agencies know millions of tons of toxins will be coming out of the plastics cracker smokestacks and into the air. They know toxic organic compounds will be flowing into the Ohio River.”

Midway through Dark Waters, Darlene Kiger (played by Mare Winningham) describes the “Teflon flu” that workers, including her ex-husband — who used PFOA — developed. “We knew something wasn’t right,” Kiger says. “But this house, we bought it just by showing the bank my husband’s DuPont ID. Put both our kids through college, engineers. And, in this town, that doesn’t come without a price.”

That’s a moral dilemma that may confront more residents along the Ohio if the petrochemical industry arrives en masse (though it’s worth noting that DuPont’s Parkersburg plant employed 2,000 directly and roughly 1,000 more contractors, while modern petrochemical plants like Shell’s ethane cracker in Beaver will employ an expected 600).

In the meantime, Dark Waters offers a look back at the extraordinary tenacity — and at times, simple luck — it took for those outside DuPont’s inner circle to begin to understand the hazards and the harms the company’s chemical contamination had caused.

Reposted with permission from DeSmogBlog.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe