Over the next couple of weeks, crews will fully remove the 125-foot-wide, 25-foot-tall dam, allowing the Middle Fork Nooksack to run free for the first time in 60 years. Ctyonahl / Wikimedia Commons / CC by 3.0

By Tara Lohan

The conclusion to decades of work to remove a dam on the Middle Fork Nooksack River east of Bellingham, Washington began with a bang yesterday as crews breached the dam with a carefully planned detonation. This explosive denouement is also a beginning.

Over the next couple of weeks, crews will fully remove the 125-foot-wide, 25-foot-tall dam, allowing the Middle Fork Nooksack to run free for the first time in 60 years. With the dam’s removal, 16 miles of river and tributary habitat will open up to help boost populations of three threatened Puget Sound fish species: Chinook salmon, steelhead and bull trout.

“This project has always ranked at the top of the list for fish recovery projects in this area because of the sheer number of miles of river habitat that are available upstream in a fairly remote and pristine area,” says Renee LaCroix, assistant public works director for the city of Bellingham, which owns the dam. “There’s no other single project in this area that can match this.”

Two local tribes, the Nooksack and Lummi Nation, have been behind the effort to help restore fish passage and the river’s ecological integrity.

“Our natural resources are our cultural resources,” says Trevor Delgado, the Nooksack tribal historic preservation officer. “With this removal we get a little piece of our home back — a place where our people have visited for hundreds of generations.”

LaCroix says the project has no downsides for the city, and it’s expected to increase the resilience of the municipal water supply, remove a safety hazard for kayakers, help fish recovery and restore culturally significant resources for the tribes.

Proponents also hope to see indirect benefits for endangered Southern Resident killer whales. This population of orcas ranges across Pacific Northwest coastal waters and relies on dwindling numbers of Chinook as a main food source. Fewer than 80 of the whales remain, and Chinook populations have fallen so low that the orcas have started altering their traditional migration patterns as they search for fish to eat.

But even with the dam removal’s many benefits and municipal and tribal support, the path to this moment hasn’t been easy.

The History

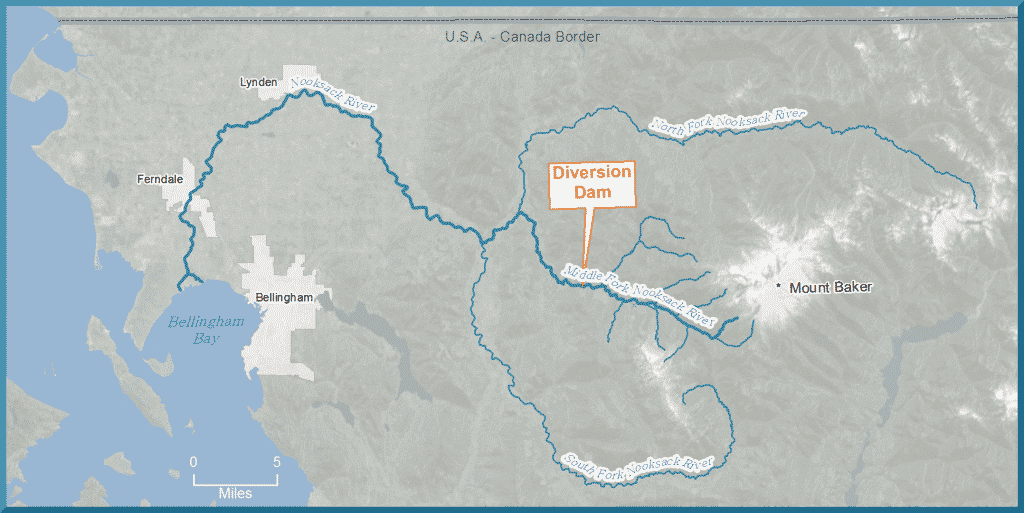

The Middle Fork Nooksack drains glacier-fed headwater streams that run off the icy summit of 10,778-foot Mt. Baker. The Middle Fork joins the North Fork and then the mainstem of the Nooksack River, which travels to Bellingham Bay and Puget Sound. The entire Nooksack watershed stretches 830 square miles across Washington and into British Columbia.

American Rivers

For generations the river and its surrounding habitat have physically and spiritually nourished Indigenous peoples — including the Nooksack Indian Tribe and the Lummi Nation.

But all that changed when the dam was built in in 1961 to divert water to the city of Bellingham to supplement its main water supply in Lake Whatcom — the drinking water for the now-85,000 residents in the city and county. As soon as it went up, the dam obstructed fish passage, altered the river’s flow, and disrupted the ability of tribal members to use a culturally significant area.

For the past four decades, Delgado says, the Nooksack have pushed for dam removal. They got close in the early 2000s, when the Nooksack and Lummi Nation entered into an official agreement with the city and state to work on a solution that would allow fish passage, including the possible installation of fish ladders. But despite years of work, a suitable fix wasn’t found, and the effort had completely stalled by 2016.

The following year the nonprofit American Rivers, which works on watershed restoration and has extensive experience in dam-removal efforts, stepped in with financial backing from the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation. American Rivers’ April McEwan assumed a project management role and brought parties back to the table and soon into agreement on a plan to remove the dam and reengineer the city’s water intake from the river.

“What we know about dam removal is that if you can remove the infrastructure and restore the channel to natural conditions, that’s always the best way to get fish passage,” says McEwan.

The final cost of the project came in at around million — way more than the city could afford on its own. About half of the cost eventually came from the state and the city is collaborating with federal agencies on the distribution of another million in Pacific Salmon Treaty funds. But before applying for that money, the city had to complete costly initial design and permitting work. Private foundations — largely the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation, along with Resources Legacy Fund — picked up 70% of those initial costs.

LaCroix says help from American Rivers and the foundations was hugely important in getting the project “shovel ready” so it could apply for the construction funds it needed.

Removing the dam infrastructure was just part of the cost, though. Reworking the city’s water intake also required some tricky engineering.

A Plan Comes Together

The Middle Fork dam is not a pool dam built for water storage. Much of the time, water flows over the top until dam operators drop a floodgate to divert water to new locations. That water travels about 14 miles through tunnel and pipeline to Mirror Lake, then Anderson Creek, and to Lake Whatcom before finally being delivered to residents’ taps.

Before removing the dam, engineers had to move the water intake 700 feet upstream and situate it at an elevation that still enabled city water withdrawals throughout the year, regardless of flow conditions.

They also needed to make sure that the rushing water didn’t sweep up fish and accidentally send them through the water-supply system.

“The solution required a fairly complex design in the intake structure, including a fish exit pipe out of that structure to put fish back into the river in a way that meets current environmental permit standards,” explains LaCroix.

Project layout for the removal of the Middle Fork Nooksack diversion dam and rebuilding of water intake. City of Bellingham

Despite the cost and the work, she says, being able to continue to meet their municipal water obligations while opening up habitat for threatened species has been a win-win.

“I think there’s a lot of benefits to having a dam removal versus fish passage — the main one being that you get a free-flowing river that can be a dynamic ecosystem and change over time,” she says. “A static fish ladder just can’t provide that same level of ecosystem benefit.”

Restoration Success

Despite local authorities’ championing dam removal on the Middle Fork, the project has largely flown under the radar, overshadowed in the Pacific Northwest by heated discussions about a much larger potential project — removing four federal hydroelectric dams on the lower Snake River, a major tributary of the Columbia River.

Proponents of dam removal there see it as the best chance for recovering threatened salmon populations, including Chinook, which could help starving Southern Resident killer whales. Those dams also provide irrigation water, barge navigation and hydropower, so there’s been more pushback against removal efforts.

Previous dam removals around the country, however, have proved successful at aiding fish recovery and river restoration.

Most notably the 1999 demolition of Edwards Dam on Maine’s Kennebec River restored the annual run of alewives, a type of herring essential to the food web. The fish run has gone from zero to 5 million in the two decades since dam removal. Blueback herring, striped bass, sturgeon and shad have also extended their reach. And the resurgence has brought back osprey, bald eagles and other wildlife, too.

The overwhelming success of river restoration on the Kennebec helped to spur a nationwide dam removal movement that’s now seen 1,200 dams come down since 1999. Last year a record 90 dams were removed in 26 states, including 20 dams in California’s Cleveland National Forest.

Spider excavators remove on dam on San Juan Creek in California’s Cleveland National Forest. Julie Donnell, USFS

The results have been seen in the Pacific Northwest, as well, which boasts the largest dam removal thus far in the country. In 2011 and 2014, the demolition of two dams on Elwha River, which runs through Washington’s Olympic National Park, opened up 70 miles of habitat that had been blocked for a century. Scientists have started seeing all five species of salmon native to the river coming back, particularly Chinook and coho. Bull trout, they’ve observed, have increased in size since the dams were removal.

Benefits on the Middle Fork Nooksack

McEwan hopes to see a similar outcome on the Middle Fork.

Like the Elwha the Middle Fork Nooksack is a relatively pristine river with little development, and dam removal is expected to provide a big boost to fish. The additional miles of spawning habitat are important, but so is the temperature of that water.

The dam removal will open access to cold upstream waters, which are ideal for salmon and getting harder to come by as climate change warms waters and reduces mountain runoff.

“This is really great for the climate change resiliency for these species,” says McEwan.

Steelhead will get back 45% of their historic habitat in the river, and scientists expect Chinook populations to increase in abundance by 31%.

That could help Southern Resident killer whales.

“When you get to the ocean, it’s a little bit of a black box in terms of what you can model and say definitively is going to help, but more fish is better for orcas,” McEwan says.

Upstream habitat will see benefits, too.

Oceangoing fish like salmon enrich their bodies with carbon and nitrogen while at sea. When they return to their natal rivers to spawn and die, the marine-derived nutrients they carry back upriver become important food and fertilizer for both riverine and terrestrial ecosystems — aiding everything from trees to birds to bears.

“Once the fish start making their way back, it will start changing the whole ecological system,” says Delgado.

But any ecological benefit from salmon restoration, either in the ocean or the upper watershed, won’t be immediate.

“The population of salmon on the Middle Fork is so low that we expect it’s going to take quite a while to rebound,” she says. “But the big picture is that what’s good for salmon is good for the region — our history and our destiny are intricately intertwined.”

After decades of work, that process of restoration has finally begun.

Tara Lohan is deputy editor of The Revelator and has worked for more than a decade as a digital editor and environmental journalist focused on the intersections of energy, water and climate. Her work has been published by The Nation, American Prospect, High Country News, Grist, Pacific Standard and others. She is the editor of two books on the global water crisis.

Reposted with permission from The Revelator.

- 4 Exciting Dam-Removal Projects to Watch - EcoWatch

- Jump-Starting the Dam Removal Movement in the U.S. - EcoWatch

- Boom: Removing 81 Dams Is Transforming This California Watershed

- Dams Significantly Impact Global Carbon Cycle, New Study Finds - EcoWatch

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe