Fred Stone holds his brown swiss cow Lida Rose at his Arundel dairy farm on March 18 after a press conference where he spoke about PFAS chemical contamination in his fields. Gregory Rec / Portland Portland Press Herald via Getty Images

By Susan Cosier

First there was Fred Stone, the third-generation dairy farmer in Maine who discovered that the milk from his cows contained harmful chemicals. Then came Art Schaap, a second-generation dairy farmer in New Mexico, who had to dump 15,000 gallons of contaminated milk a day.

While the pollutants in these cases were different, they both belong to the same class of chemicals: per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS for short. Numbering in the thousands, the chemicals are used to make a variety of products such as nonstick pans, stain-resistant rugs, water-repellent clothing and food packaging. Industries have been manufacturing most PFAS since the 1940s, but the effects these chemicals have on human health started surfacing only in the past decade or so. Exposure has been linked to serious conditions, including testicular and kidney cancer, colitis, thyroid disorders and suppressed immune systems in children.

Many states are just beginning to look for PFAS contamination in drinking water and elsewhere, and places like Michigan, where state officials are actively testing for (and finding) these chemicals, are starting to look like contamination hot spots. In reality, the PFAS problem is much more widespread.

While Teflon plants and military bases that use firefighting foams are common PFAS sources, another culprit is emerging: sludge produced by sewage treatment plants. Farmers all over the country use such sludge to fertilize their land, potentially contaminating the crops and livestock they produce. And it could be happening in the Midwest, too.

Wary in Wisconsin

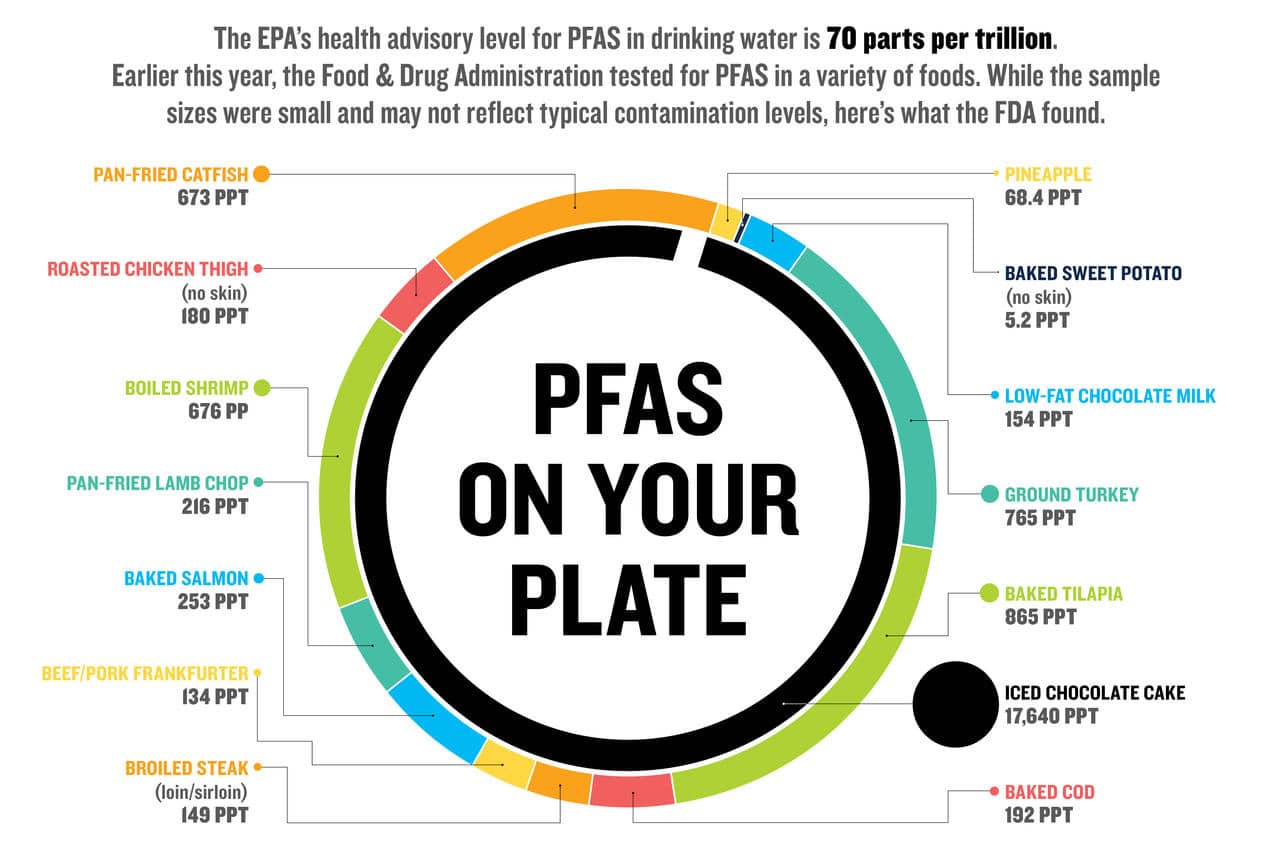

Doug Oitzinger, the former mayor of Marinette, Wisconsin, was at a meeting to discuss a new community garden last year when he found out about his town’s groundwater. Just 30 feet below where they stood, levels of PFAS were as high as 33,000 parts per trillion (ppt), more than 470 times the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s health advisory level for drinking water of 70 ppt — a concentration many experts and states still consider a threat to human health. A few months later, Oitzinger knocked on a neighbor’s door to see if anyone had told her about the pollution pooling below her home. She said she hadn’t heard a thing.

In the beginning, he thought the contamination was limited to a specific area at the edge of town, close to the Tyco Fire Technology Center run by Johnson Controls International. But the more Oitzinger researched, the more concerned, and angry, he became. He’s now pushing for Wisconsin politicians to make the PFAS issue a top priority. “I went from somebody who thought this was an unfortunate thing Tyco didn’t know about, to … well, let’s just say their hands are covered in some pretty nasty stuff,” he said.

Tyco knew back in 2013 of its PFAS problem, according to records it submitted to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR), but it wasn’t until 2016 that the company documented the chemicals on its property and in the groundwater nearby. The public found out about it only in 2017, four years after Tyco’s original admission, when the company acknowledged to the DNR that its pollution could be spreading.

When Tyco disclosed that PFAS pollution had contaminated groundwater in Marinette and nearby Peshtigo, the DNR directed the company to find affected wells. Since December 2017, Tyco has been voluntarily distributing bottled water to more than 120 households and installed 37 water treatment systems in the community. But it’s not enough, and drinking water isn’t the only thing in jeopardy. Just like other PFAS manufacturers, Tyco sent its waste to a local sewage treatment plant, where farmers obtain sludge for fertilizing their fields.

“We foolishly thought that we had institutions that would protect us from this sort of thing, that this couldn’t happen anymore,” said Oitzinger. “What we’ve discovered is that those institutions didn’t protect us.”

The DNR has since asked the wastewater treatment facility to stop selling sludge to farmers and launched a larger investigation into the matter earlier this year. For many farm owners, however, this action may have come too late — and there are no quick fixes. PFAS do not easily break down and can persist in the environment for decades, if not centuries.

A Message From Maine

The Stone family had been raising dairy cows in southern Maine for close to a century when, in 2016, Fred Stone voluntarily checked the farm’s milk for PFAS. What he found, he said, destroyed his life: levels as high as 1,470 ppt.

“The toxic chemicals that I never used and had never even known about until two years ago contaminated my cows — which I really take exception to — and ruined my farming operation and hurt my family,” he told reporters at a March press conference.

Stone had spread PFAS-contaminated sludge and paper mill ash on his fields for 20 years, but he stopped that practice in 2004. After 15 years, the substances were still there in amounts that could severely taint the milk of Stoneridge Farm, which is now out of business.

Stone went to Washington, DC, to ask Congress do something about PFAS contamination. Back in Maine, legislators set a PFOS action level of 210 ppt in milk, and the governor set up a PFAS task force. Maine’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) temporarily stopped allowing farmers to spread sludge on their fields until it was tested. In 44 sludge samples taken by the agency, all but two had levels that exceeded the state’s new limits for three PFAS chemicals: PFOA (2.5 parts per billion), PFOS (5.2 ppb), and PFBS (1,900 ppb). The DEP also tested retail and raw milk from three other farms, where PFAS levels did not exceed the state’s reporting limit of 50 ppt.

So far, Stone’s is the only Maine farm to shutter due to PFAS contamination, but others could follow and clean fields are still at risk. The Maine-based nonprofit Environmental Health Strategy Center has been pushing for the state to investigate other farms that received sludge from the same place as Stone, said Patrick MacRoy, deputy director of the group, but the group hasn’t yet gotten a list of such farms, and testing isn’t mandatory.

Beyond Milk

Even though no federal PFAS standards exist, lawmakers in a few states such as Vermont, Michigan and New Hampshire have proposed or passed bills that limit various types of PFAS — at differing concentrations — in drinking water. For Wisconsin’s water supplies, the state’s Department of Health Services recently recommended limits for PFOA and PFOS, two of the most widely used types, at 20 ppt. These are moves in the right direction, but PFAS find their way into more than just water. Researchers have been detecting these substances in everything from fish to leafy greens and grains to iced chocolate cake.

According to a 2012 study conducted by the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, a branch of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, “a number of researchers have concluded that food is often the primary human exposure route” for PFAS. (A 2016 EPA report agreed that diet is a primary source.)

Milk containing PFAS tends to be particularly potent because the substances bioaccumulate in cows. Farmers spread sludge on fields, plants take the contaminants up from the soil, then cows eat the grass in great amounts, concentrating the PFAS, which end up in their milk. That’s bad for children, who tend to drink lots of milk and are also more vulnerable to these substances than adults are.

“Yes, exposure from milk is likely less than drinking water for adults, but for infants and children it’s different,” said Anna Reade, an NRDC staff scientist specializing in toxic chemicals. “It could be a significant source of exposure, and they’re the most vulnerable in our population. We have a responsibility to protect them.” Yet so far, no state except Maine has begun to develop a PFAS standard for milk — or any other food, for that matter.

The 2012 study showed that PFAS levels in 49 milk samples taken from around the country didn’t contain levels higher than the EPA health advisory level of 70 ppt except for one — taken from a dairy farm where sludge was spread. Locations where we know farmers spread contaminated sludge are good places to be testing, said Erik Olson, NRDC’s director of health and food.

In Wisconsin, the DNR has a map of where the state’s farmers have spread biosolids from the wastewater treatment facility used by Tyco, and staff have tested the farms’ soils and their surface water and groundwater. The results are expected this fall, but the agency hasn’t yet indicated whether it will also test the foods grown on these farms.

Needless to say, tensions are high in these parts. “This is like coming to someone and saying your house is radioactive,” said Oitzinger.

NRDC’s Reade suggests that state agencies test sludge before it’s spread on fields and milk before it goes to market. Then officials could see where the highest PFAS concentrations are coming from. But she knows that’s not a popular idea. “PFAS is a huge, global public health threat,” she said. “It’s going to be hard to test for all this.”

In July, the Wisconsin DNR urged 125 sewage treatment plants to test their waste products, but the agency has yet to set a PFAS standard for sludge or milk. Oitzinger hopes to change that. He’s now working with a small group of activists and Wisconsin lawmakers to put PFAS standards on the books in his state, but he fears for the rest of the country, too.

The problems with these chemicals are complex, he said, and as Stone knows, they don’t go away on their own. “It’s like peeling an onion,” he said. “Every time you take a layer off, there’s another layer, and the more layers you take off, the more your eyes water. It just gets worse and worse.”

- What Are 'Forever Chemicals' and How Are They Getting in Your ...

- PFAS Chemicals Contaminate U.S. Food Supply, FDA Confirms ...

- Forever Chemicals Found in U.S. Mothers' Breast Milk

- Forever Chemicals Found in Home Fertilizers

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe