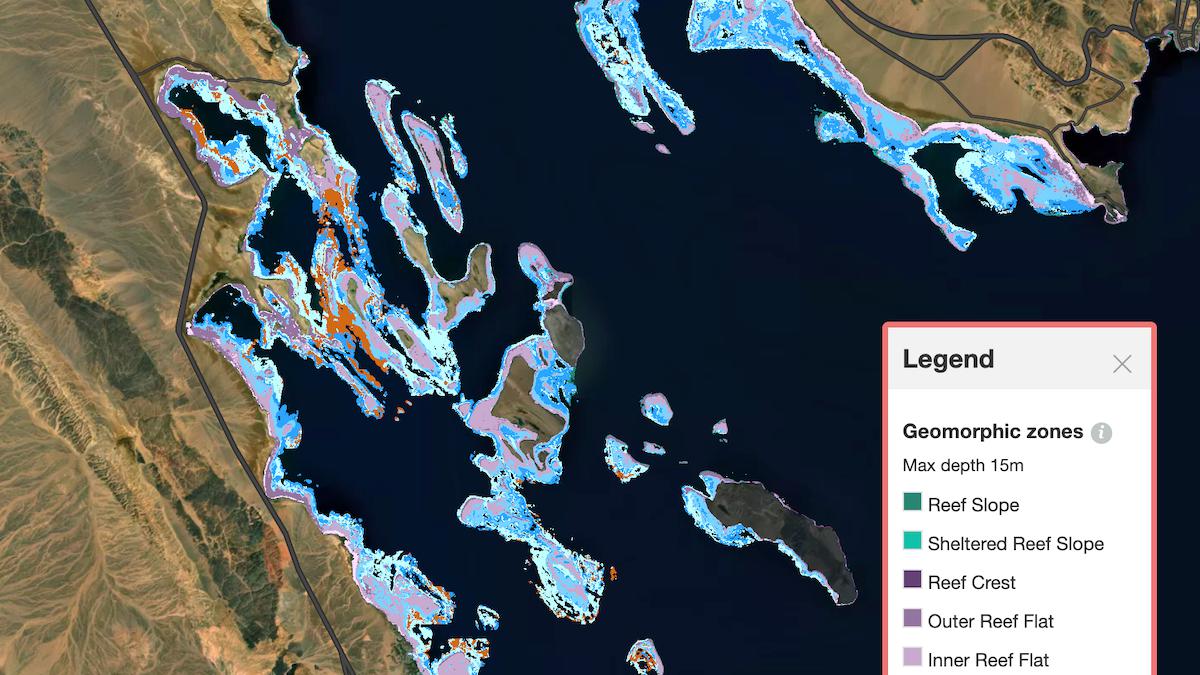

Geomorphic maps communicate the seascape or structure of the

ocean floor. There are a total of 12 geomorphic classes identified on the Allen Coral Atlas. Allen Coral Atlas

A unique partnership has produced the first-ever high-resolution satellite map of the world’s shallow coral reefs.

The Allen Coral Atlas announced its completion Wednesday as a tool that policy makers, conservationists and the general public can use to understand and preserve the world’s reefs at a time when they are under increasing threat from the climate crisis and coastal development.

“We’re trying to create a kind of moral mirror that we hold up to humanity,” Andrew Zolli, vice president of sustainability and global impact at Planet, the company that provides the satellite images for the project, said in a press conference.

A Digital Public Good

The atlas is the product of three years of work, more than 450 research teams and nearly two million satellite images. It was named for the late Microsoft co-founder and philanthropist Paul Allen, who was an early instigator of the project.

However, the atlas was a team effort. The high-resolution satellite imagery is provided and regularly updated by Planet. Arizona State University then cleans the images and the University of Queensland uses machine learning and regional data to generate different map layers. The National Geographic Society trains conservationists in how to best use the map, while Allen’s company Vulcan funded the website that makes it accessible.

“One of the things that the Atlas represents is a kind of digital public good,” Zolli said.

An Allen Coral Atlas partner looks at a map during development of the Atlas. Allen Coral Atlas

It is also a major milestone. Previously, only 25 percent of the world’s reefs had been mapped using high-resolution images, and there was no consistent mapping process linking the different regions.

“It’s quite an undertaking that hadn’t been achieved at this resolution and with this kind of detail,” director of Arizona State University’s Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science Greg Asner said during the press conference.

The only limit on the project is depth. Current satellite technology, Asner said, can only “punch through the seawater” to about 15 meters (approximately 49 feet). Which is why the atlas offers data products that extend from either zero to ten meters (approximately 33 feet) or zero to 15 meters.

Dr. Alexandra Ordonez Alvarez from University of Queensland collects georeferenced data in Far Northern Great Barrier Reef on Ashmore Bank. Chris Roelfsema

Conservation Tool

The map also comes at a pivotal moment for the world’s coral reefs and the ecosystems and human communities that depend on them.

“Coral reefs are sort of at the nexus of the climate and biodiversity crisis,” managing director for government and community relations at Vulcan Chuck Cooper said at the press conference.

The atlas, therefore, is designed with special tools that can help governments and scientists respond to these crises. National Geographic Society program manager Brianna Bambic said the predominant use so far was in the planning of marine protected areas.

The atlas provides a layer called a benthic map, which helps planners see where different types of habitat are located on the reef, such as coral or seagrass. It also provides a layer that allows planners to see which areas are already protected.

“We now have the highly detailed coral reef maps needed to create new spatial plans and marine protected areas. These map layers would have taken us five years to create and only if we had the budget or resources to do so, which we do not,” Wen Wen, a marine spatial planner in Indonesia, said in a press release. “The Allen Coral Atlas is playing a large role in prioritizing 30 million hectares of a new Marine Protected Area zoning plan and providing alternative locations for a coastal economic development project that is environmentally sustainable. This tool is a blessing to our country.”

This type of use is expected to become even more important as countries are set to convene at a summit of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity in Kunming, China next year. One goal that is expected to come out of that conference is the aim of protecting 30 percent of land and water by 2030.

“The coral atlas is going to be a really valuable tool for them to do that,” Cooper said.

Indeed, countries like Mozambique and Fiji that have already committed to the goal are in the process of using the atlas to choose what part of their coastline to protect.

Reef Restoration

In addition to helping determine what parts of reefs to preserve, the atlas can also be used to determine where to restore coral reefs.

This is something that the nonprofit Coral Vida is doing in the Bahamas, Asner said, by using a layer called the geomorphic map. While the benthic map is more biological, the geomorphic map shows the physical or geological contours of the reef and can be used to determine the best location to plant new corals raised in nurseries.

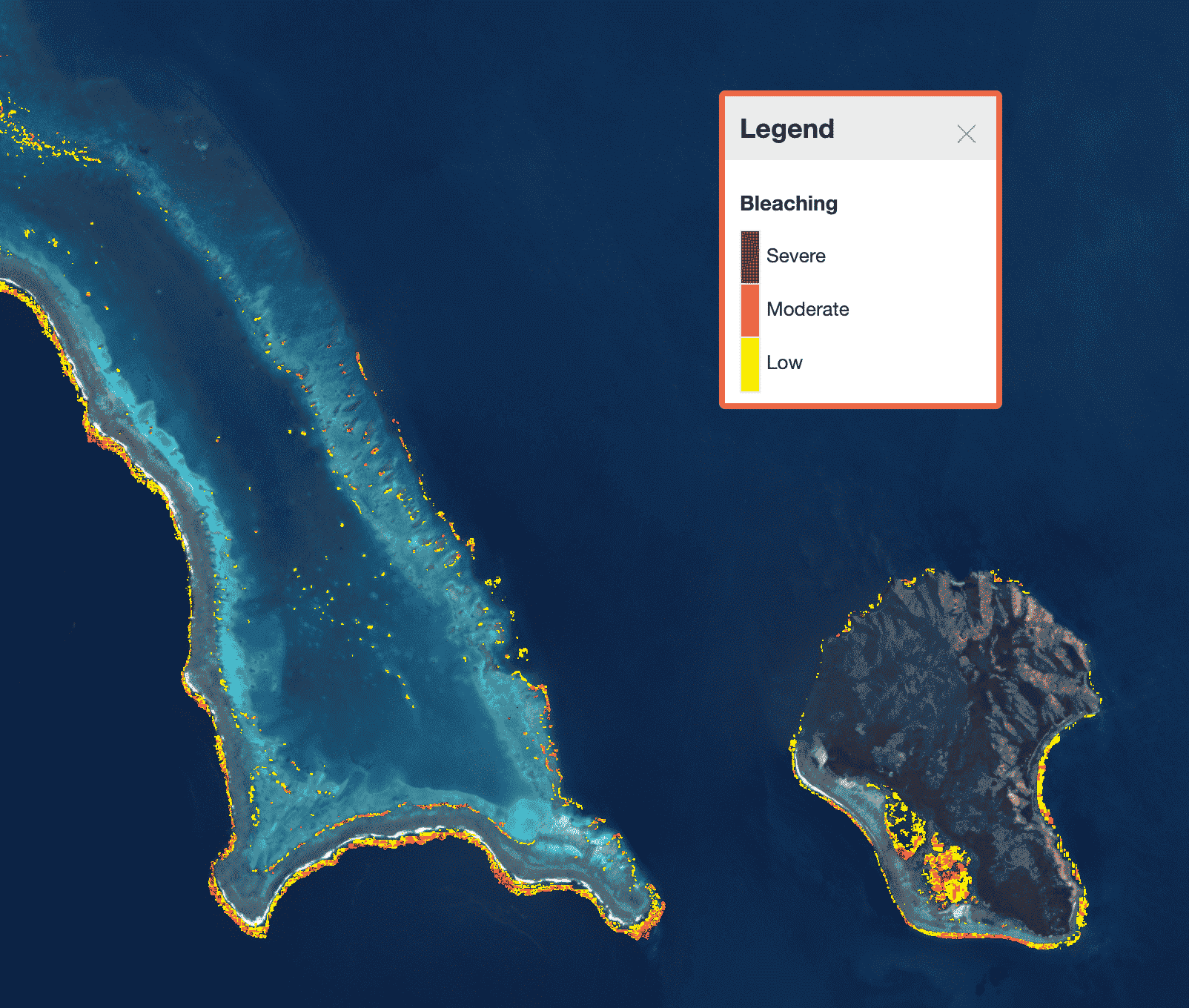

In addition, the Allen Coral Atlas also includes a bleaching monitoring system updated every couple of weeks to tell users when a reef or part of a reef may be suffering a bleaching event. This is what happens when warm water forces coral to expel the algae that gives them nutrients and color, and is an increasing danger as the oceans heat up. The monitoring system enables conservationists to see what parts of a reef might be susceptible to bleaching so as not to attempt to plant new corals there.

Asner said he originally developed the bleaching tool in the Hawaiian islands, where it had another use. His team worked with the government to determine six things concerned citizens could do to reduce stress on the reef once bleaching was detected, such as limiting their fishing on the reef.

Limiting extra stress, Asner said, “can spell the difference between surviving and not surviving among corals,” during bleaching events.

“That was successful, we believe,” he said, “and we believe that that sort of approach can be implemented by governments… or anybody using our bleaching tool.”

Child Efforts

Now that the team behind the Allen Coral Atlas has developed the technology and partnerships that made it possible, they do not plan to rest on their laurels.

One goal, Asner said, is to integrate coastal data into the atlas.

“Climate change is one of the big problems that reefs are facing, but coastal development and coastal impacts are just as important,” he said, “and so you’ll see us expanding into that realm over the next couple of years.”

On a larger scale, Zolli said that developing the atlas showed the team the kind of collaboration that is needed to solve other major challenges. There are now “child efforts” of the atlas to create similar digital public goods for forests or greenhouse gas emissions.

“This approach is as important as the outcomes that it generated,” he said.

The Allen Coral Atlas recently released the world’s first satellite-based global coral reef monitoring system, shown here with New Caledonia bleaching data for the May 10, 2021 biweekly period.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe